Sylmar woman is now post-fire keeper of the flame

- Share via

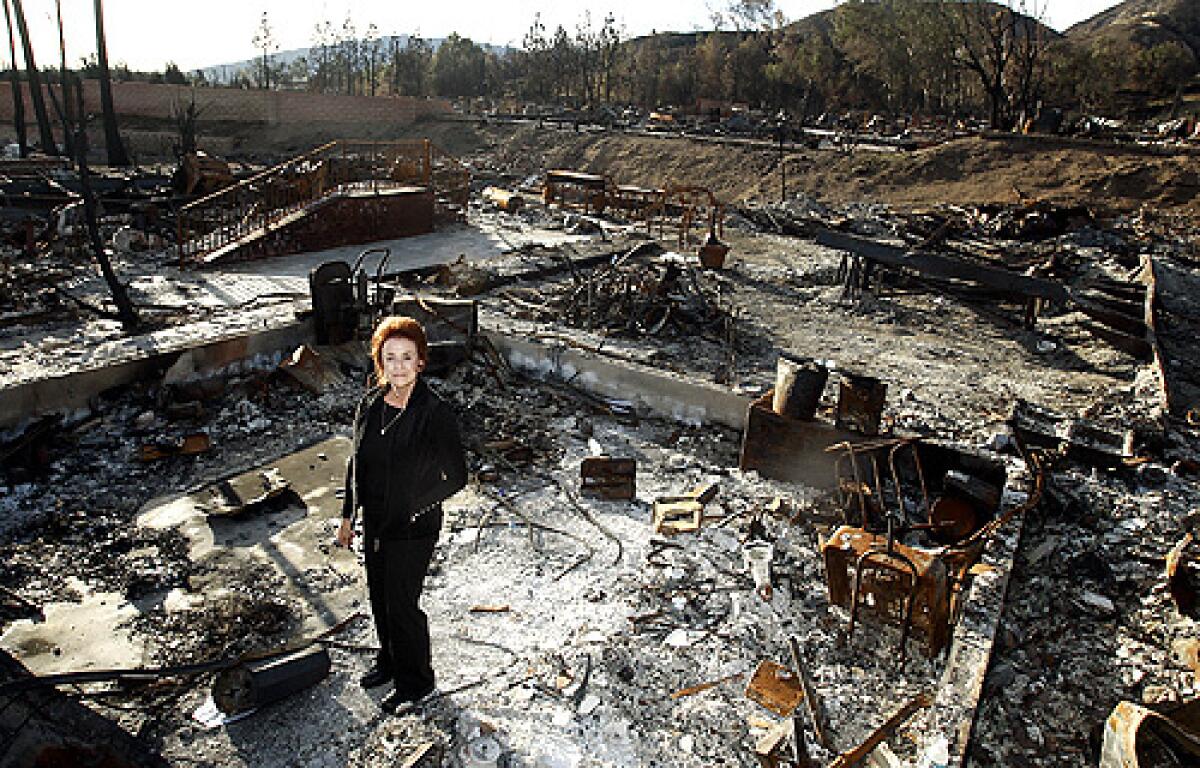

Ginny Harmon, burnt-red hair teased into her trademark bouffant, hits the brakes of her white company minivan along nearly every street. She pauses for seconds, sometimes minutes, to talk about what once was.

There were red roses climbing up verandas, she says, elaborate brickwork, antique lampposts, fireplaces and fish ponds.

Number 60 was where her hairstylist lived. Every week, Harmon and other neighborhood women stepped out of the stylist’s den, past her white picket fence and onto Oakridge Street smelling of sweet hair spray.

Number 173 belonged to a couple returning to live in the Sylmar park for the third time. They had just spent $60,000 to turn their 2,000-square-foot house into “paradise” for themselves and their grandchildren.

Number 96 was home to a maintenance engineer and his black-and-white cat, Kazoo. Everyone saw the 13-year-old deaf feline gazing lazily from his favorite window as they drove past.

Now patio furniture juts out of the ground like abstract art. Palm trees tower overhead like charred matchsticks. Signs asking neighbors to help find Kazoo -- missing since the night of the fire -- are posted everywhere.

The only things that distinguish one life from the next in nearly 200 acres of rubble are the improvised house numbers, spray-painted in neon orange at the edge of each driveway. The lots, 1 to 600, are etched in Harmon’s mind. So are the people who lived in the Oakridge Mobile Home Park, the community she managed for more than two decades.

In the early hours of Nov. 15, all but 99 houses burned to the ground and 40 others were badly damaged. Residents fled 50-foot flames and scattered across the Southland into hotels, apartments and relatives’ homes.

“There was nothing that could have stopped it,” Harmon says. She left with only the clothes she was wearing and one other outfit.

Each day on her way to work inside a trailer parked a few feet away, she passes by the spot where her dusty rose house once stood. Any mention of her home and her face grows somber.

Harmon still can’t bring herself to sift through what little remains -- brick steps, charred metal, shards of blue and white porcelain.

Reduced to soot: rooms decorated with Asian-themed furniture, the artwork she bought during trips to China. There was no time to grab her coin collection or any of the treasures gathered over her lifetime. She has yet to let herself cry.

“I don’t want to feel bad,” she says. “I have to stay strong for everyone.”

Harmon drives to Oakridge each morning from a nearby apartment building where she and about 100 other neighbors have taken up what they hope will be temporary residence. As she pulls into her parking spot next to the brown trailer, she often sees a handful of people waiting to talk with her.

Utility company workers, insurance claims adjusters and representatives of federal and local agencies pour in with questions, requests and propositions throughout the day.

Her most serious discussions usually wait until she is behind her desk, a utility table stacked high with paperwork. She rises to greet each person. She listens closely, memorizes most of what they tell her. The rest she jots down in graceful cursive letters on notebook paper she then tapes to the trailer’s wood-paneled walls.

Her notes, on yellow, white and orange pieces, are everywhere:

# 491 Get price for cleanup

Measure # 535

# 376 included as a house to be demolished

On one table, a note to homeowners:

Oakridge folks, beware! There are some dishonest and uncaring people out there whose primary interest right now is to separate you from your money.

In all, Oakridge was home to about 1,700 people, a mix of young families and senior citizens. Harmon makes time for anyone who asks to see her, even if only for a quick hug or chocolate mint.

“I’m like their mother, their minister, their psychologist,” she says.

She spends half an hour talking with two young siblings who had recently bought their mobile home and finished moving in two weeks before the fire.

Each story she hears seems more heart-wrenching than the last: A woman still mourns the absence of her husband and son, who both died less than a month before the fire. A family of four had lost it all once before in another blaze. A man had bought his home with cash and had no insurance.

Most homeowners are counting on insurance companies to put their lives back in place. As of Dec. 23, more than 500 Oakridge residents had asked the Federal Emergency Management Agency for help with rent, home repairs and other needs. At least $1.2 million has been doled out to nearly 100 households.

The city is preparing to hand out $500,000 to help families relocate and fix damaged homes. It also provided $75,000 in hotel vouchers. Councilman Richard Alarcon, who represents the district in which Oakridge lies, plans to set aside an additional $100,000 in relief.

“Many people will forget about the fires,” Alarcon said. “But we will have to keep working very hard to tackle problems that will keep emerging.”

Perhaps no one is working more on behalf of the Oakridge residents than Harmon. Her goal is to put back together a community she has been part of since it opened in 1979. She moved into her home, satisfying a longing to be surrounded by mountains, with her then-husband. She stayed after they parted.

With relatives 2,200 miles away in Ohio and no children of her own, she considered park residents family. She became its caretaker. When the Northridge earthquake shook all 600 homes off their foundations in 1994 -- forcing neighbors to live in one another’s garages and driveways while the homes were re-leveled -- Harmon rushed to hand out food donations and shelter pets and families in the clubhouse.

For 23 years, the sixtysomething woman (she declined to give her exact age) cracked down on scofflaws and the less-than-tidy, enforcing park rules. If someone’s lawn needed mowing, house needed painting or Christmas lights were still flickering in late January, Harmon sent a notice. She drove around in the park’s white van after dark, inspecting each street through her purple-tinted glasses.

“She could be a pain,” said Christine Gayles, who lost her home on Olive Street. “But if she wasn’t like that, we wouldn’t have had the high standards that we had.”

Before the fire, Harmon’s diligence meant Oakridge looked far different from the stereotypical trailer park -- residents considered it the “Beverly Hills of mobile home parks.” Locking the door was optional. Families marched down the street with their dogs and American flags for the annual Fourth of July parade. Homeowners meandered along the streets in golf carts with Mercedes-Benz emblems.

There was 24-hour security guarding the gate and a 15,000-square-foot recreation center with tennis courts, Jacuzzis, a gym and “an almost Olympic-sized” pool.

Residents organized trips to the theater and ship cruises. This winter some neighbors still intend to take a long-planned vacation on the Mexican Riviera.

“It was an exceptional community,” Harmon says. “It really was.”

A month after the blaze tore through the park so fast that even firefighters were forced to flee, utility trucks slowly rumble down the streets examining cooked gas pipes and sewer lines. Even those whose homes didn’t burn cannot return until utilities are again available.

At a time when festive Christmas lights would have hung along each street, the park is deserted, silent except for the rustle of parched leaves.

Most residents tell Harmon they want to return. But it will be four months to a year or more before anyone can.

As an older couple settles across from Harmon inside the management office, she listens closely. They ask about rebuilding and moving on with their lives. Outside her door, five others wait their turn.

She reaches for floor plans to show them what is proposed for the new homes. They watch as Harmon explains their choices, her finger gliding past the kitchen, the living room, the frontyard where new roses might one day grow again.

“It’s going to be beautiful,” she tells them. “Even better than what we had before.”

esmeralda.bermudez @latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.