In Norco, trouble on mane street

- Share via

Ten years ago, after Judee Haddock married off the last of her three children, her house in Orange County suddenly felt very quiet. She was 53 years old -- far too young and far too healthy, she figured, to sit around listening to the floorboards creak.

“No more kids. No more husbands,” she said with a chuckle. “Time for a change.”

She bought a house in Norco, in the northwest corner of Riverside County. The place was a dump; her children were aghast. She tore it down to the frame, and piece by piece, put it back together, with flowering shrubs in the front to filter out the dust and high society garlic bushes in the back. Soon it was a refined country home. City Hall gave her a beautification award.

“All by my lonesome,” she said on a recent afternoon. “Well,” she added, almost apologetically, “with the help of the manure, of course.”

Of course.

Every morning, Haddock picks up behind her two horses, Dakota and Teepee, who live in her backyard corral. She dries their droppings in the sun, grinds them down a bit with a small tractor, then sprinkles them over her landscaping.

She has become quite fond of the routine, but she may not do it for much longer. Because Norco -- self-proclaimed “Horsetown U.S.A.,” where riding, training and breeding horses comprise the sum of civic identity, where there are hitching posts outside the Rite-Aid and the Saddle Sore Eatery & Saloon -- is at war over manure.

The city is divided over several manure-related issues. There is a pending battle over whether new fees should be levied to pick up large bins of manure from businesses and a proposal to convert manure into electricity. But the most divisive issue is whether City Hall should be able to dictate the manner in which manure is disposed of -- or whether homeowners should be allowed to do with it as they please.

Many Norco residents have watched in recent years as communities across Southern California that once harbored horses have passed increasingly stricter rules that have driven out horse lovers. Norco, locals believe, is all that is left.

“This is the last mecca, the last Alamo of horse country,” said former Mayor Harvey Sullivan, 68, a retired electrician.

That’s why, to critics like Haddock and Sullivan, the debate is about something greater than horse manure. City Hall has been reminded that the only thing Norconians love as much as their horses is being left alone. Proposed rules requiring pick-up, opponents believe, are nothing less than an assault on their lifestyle.

“We think it’s a bunch of hooey,” Haddock said. “Your home will not be your home anymore. It’s that simple.”

City officials say their hand was forced.

Two years ago, Norco was fined nearly $80,000 after water quality officials determined the city had not “established a mechanism to adequately address pollutants from horse manure.”

One concern was that pollutants could be carried by storm water into creeks and underground water supplies.

The report estimated that there were about 20,000 horses in Norco’s 14 square miles. If that’s true -- there have been estimates as high as 50,000 -- the water quality officials contend that Norco generates a million pounds of manure every day.

To some residents, the report was startling. City officials responded in part with a proposed ordinance that would require residents to put manure in trash bins for removal.

City officials are expected to vote on the proposal in comings weeks -- and say additional regulation is likely.

“There are people who just don’t worry about keeping their corrals clean,” said Berwin Hanna, who stepped down as president of the Norco Horsemen’s Assn. in 2007 to serve his first term on the City Council. “I think it’s just unhealthy as heck to have it lying around.”

The movement toward regulation, however, has created an unusual dynamic: Both sides of the dispute are convinced that the other is threatening Norco’s future.

Proponents of additional regulation say water quality officials could come down with far harsher measures if steps are not taken to address their concerns.

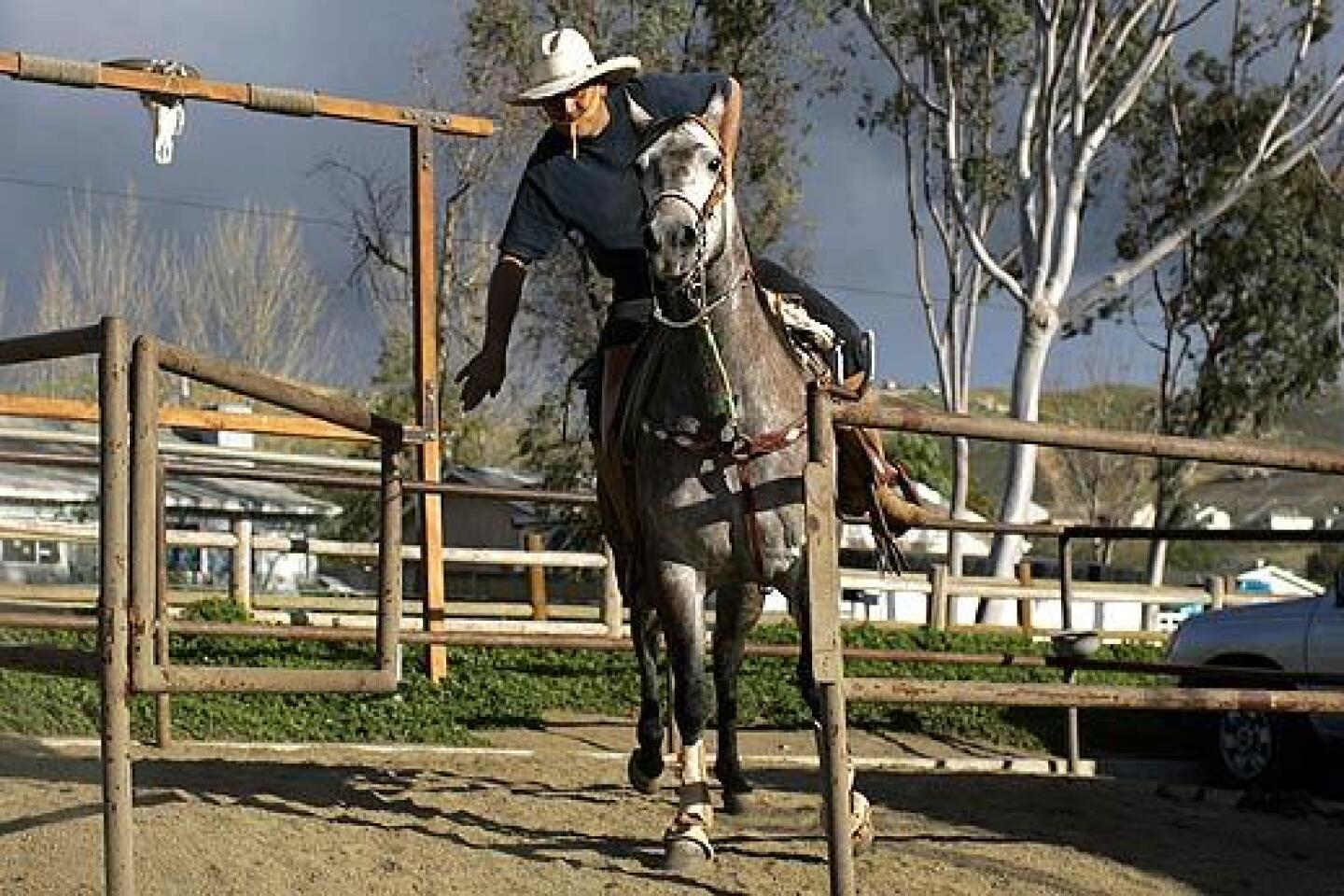

Edward “Buzz” Riebschlager, 52, came to Norco in 1982 on vacation and never left. He’s a horse person to the core -- so much so that as a teenager he was angry when he grew because he became too big to jockey. He’s now one of the city’s top horse trainers.

“If we don’t do something” about manure, it’s going to mess things up, he said. “You don’t want to lose the horses. And that will happen.”

Critics of the new rules say they would imperil a cherished sense of freedom.

“Most people here do pick up manure,” Sullivan said. “They just don’t want to be told that they have to.”

At last count, there were 27,000 people in Norco. No one is sure, however, how many horses there are.

There’s a reason for that.

Though towns on every side have exploded in population -- Ontario to the north and Corona to the south, to name two -- Norco has remained a picture of stability.

The city has kept a close eye on development; last year, planners rejected an application to build a Bob’s Big Boy restaurant until the chain agreed to outfit the chubby mascot in a giant cowboy hat and boots.

The town’s stability is rooted in Norco’s community of libertarian, don’t-tread-on-me mavericks who are resistant to change and protective of their civil liberties -- and frequently stake out those positions while on horseback.

Sullivan confessed that toward the end of his term on the City Council, his wife was furious with him for supporting an ordinance requiring children to wear helmets while riding. About 10 years ago, a council candidate proposed replacing the horse trails along Sixth Street, a main commercial drag, with sidewalks.

“He did not win,” said Glenn Hedges, president of the Norco Horsemen’s Assn. “He just about got himself hung instead.”

In that environment, the city has attempted time and again to count the horses. And time and again, the bureaucrats have been told to mind their own business.

The conventional wisdom is that the city wants to count horses simply because officials want to start licensing them, in the same way that dogs are.

That would be, in effect, a tax hike. More taxes would mean greater government influence and regulation. Next thing you know, you aren’t in Norco anymore; you’re in one of those fussy towns where you have to get a permit just to change the oil on your truck -- in your own driveway, for goodness’ sake.

“Norconians are all the same,” Hedges said. “People just don’t like other people looking in their backyard.”

That’s why going from a dispute over manure to a claim that a way of life is under attack is less of a leap here than it might be elsewhere.

It isn’t so much the broad pieces of the pick-up proposal that rankle critics. It’s the idea that if people decline to take part, city officials could have the right to inspect their property.

Might residents, Sullivan asked, start ratting out their neighbors? “Will people stop inviting people into their backyards?” he said.

Sullivan has 13 horses in his backyard. Occasionally, he lets them go into the frontyard too because, he says, “it beats mowing.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.