Housing downturn is a jolt to upscale Temecula

- Share via

For almost 20 years, they’ve been painting the town red in Temecula.

Atop onion fields and grazing pastures, they’ve built a parade of 4,000- and 5,000-square-foot houses -- palaces, many of them, with turrets and faux backyard grottoes, with six-car garages and children’s playrooms larger than the average Manhattan apartment.

Today, they’re painting the dirt green.

“Here’s one now,” code enforcement officer Jean Voshall said as she pulled her hulking pickup up to the curb in a gated community called The Fairways.

At first glance, the house looked like so many others in Temecula: five bedrooms, mushroom-colored stucco walls, a seven iron away from a dapper golf course where two men prepared to tee off. A closer look at the lawn, however, revealed that it was dead and crunchy -- and had been spray-painted green.

The paint came courtesy of neighbors, in the hope that it might be less evident to passersby that the house was empty -- foreclosed and left to the elements, with no running water, no electricity and little chance of new occupants any time soon.

It wasn’t supposed to happen here. Not like this. The crashes are expected to hit hard in the Fontanas and the Perrises of the world -- cities marketed more to working-class buyers, first-time buyers or sub-prime buyers. Indeed, Temecula is by no means the hardest-hit area of the Inland Empire; many communities here have plunged into record levels of foreclosure.

Still, the downturn has been startling here because Temecula has been sold, successfully, as a sort of Napa of Southern California: a place of wineries and hot-air balloons and Mediterranean-style bluffs that trap the sea air, even this far inland.

From the start -- Temecula was incorporated in 1989 -- the city was protective of its image.

Residents are prohibited from working on their cars, in most cases, in front of their own houses. Stores that sell spray paint are required to keep it under lock, though graffiti is almost nonexistent. Behind City Hall, there is a “sign jail” full of political ads and business ads that were yanked because they violated Temecula’s strict sign rules.

Based largely on that image, the population has nearly doubled again this decade, rising from about 57,000 in 2000 to 101,000 today -- 14 new residents a day.

Today, said Rich Johnston, Temecula’s deputy director of building and safety and code enforcement, as many as 15% of Temecula’s 22,500 single-family homes are bank-owned or in some stage of foreclosure.

Voshall said her supervisor asked city code enforcement officers to put together a master list of vacant houses. That was two months ago. She hasn’t finished because of the sheer volume. She said she has 200 on her list -- her district covers about a quarter of the city -- but she is finished with just a fraction of the survey.

“We just have so many cases,” Voshall said.

Inspectors have found squatters in some houses. Youths were recently caught growing pot behind one vacant house. Some owners have just dumped belongings in the yard on their way out -- “even silverware,” Voshall said.

Reports of “green pools” -- swimming pools at abandoned homes, green with algae -- were up 45% in the first three months of 2008 compared to the previous year, officials said. Those pools “are almost guaranteed to breed mosquitoes,” said Kelly Kersten, a county environmental health technician. He said West Nile virus is a concern.

At a home off Loma Linda Road, Kersten used an electric screwdriver to open the gate of an abandoned house. The backyard was enormous -- and apocalyptic looking, with weeds growing unfettered and a rusting swing set swaying in the breeze.

The pool was bright green, with a dead bird and other debris floating in the middle. Kersten dipped a cup in the muck, then peered into his sample. “Oh, yeah,” he said. He retrieved pesticide from his truck, then began spraying it into the pool.

“Watch,” he said. “The pool is going to start to percolate.”

In seconds, the water churned with thousands of larvae and pupae, each trying to escape the poison. Kersten locked the gate again, saying he would do his best to keep pace.

“My record is 17 pools in five hours,” he said. “But that’s really pushing it.”

In his truck, he had a list of 50 addresses with a green pool. The next day, his supervisors would add seven more.

Mayor Pro Tem Maryann Edwards moved to Temecula 21 years ago from Orange County, like many others. There were 18,000 people and one stoplight. Since then, the city has spent $1 billion on its infrastructure. It has no debt, she said, and a $12-million reserve.

Sitting in her office at Mission Oaks National Bank, where she is vice president, she rattled off the city’s accomplishments.

Despite the growth, crime has remained low, she said. There is a police officer for every 910 people, and the average response time is less than five minutes. The city just dedicated its 38th park. A big Mercedes-Benz dealership is moving to town and Abbott Laboratories, a large employer, is preparing a 300,000-square-foot expansion.

“It ain’t bragging if it’s true,” Edwards said with a smile and shrug.

Still, even a booster such as Edwards has come to recognize that Temecula has not escaped the downturn. She is helping to usher in a new ordinance that would require owners of foreclosed houses to register with the city. The ordinance, based loosely on similar rules in other cities but designed as a partnership between City Hall and property owners, is expected to help Temecula prevent abandoned homes from falling into disrepair.

“The goal is safety, No. 1,” she said. “But No. 2, the goal is to have the homes properly maintained so that people will buy them.”

Even with such steps, many fear that the road to recovery will be long and painful.

In a business park near Edwards’ office, Bob Smith was presiding over a going-out-of-business sale at a children’s store called Cat’s Cradle, which he manages. Merchandise had been discounted by as much as 90%.

Much of the store’s business was in children’s furniture: cribs, changing tables and such. Many of those sales were made to people filling a new house with furniture or those who were using home equity lines to shop.

With the real estate collapse, those customers vanished. On average during its seven years, the store drew from 60 to 80 customers on a weekend. In March, that number dropped dramatically; on some weekends, the store drew five customers. Four other furniture stores in the area have gone out of business, Smith said.

“It was shocking,” said Smith, 50, who will be out of a job after the store closes. “We’ve done all the advertising we can. We’ve done all the promotions we can. There’s nothing left to do but close up. I wonder if people understand just how bad the economy is right now. Temecula just grew too fast.”

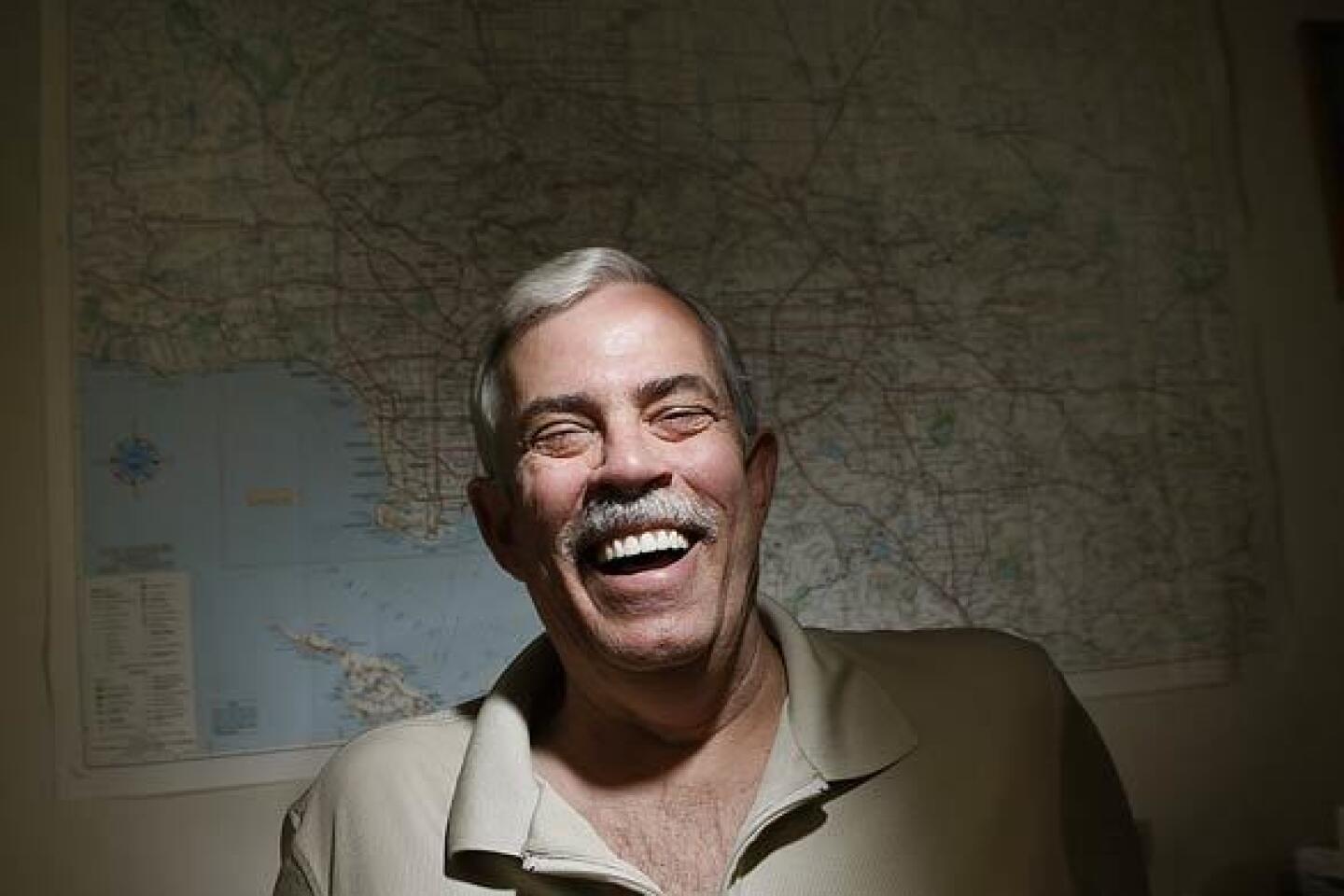

Gary Lupo, who has been in Riverside County real estate for 31 years, specializes in conducting assessments of houses for banks. He said homes in the area could lose 80% of the gains in value that have been made since 2001.

“This was all caused by greed -- on the part of everyone,” Lupo said.

Now toward the end of her day of inspections, Voshall pulled her truck onto Kingston Drive in a tidy subdivision south of Highway 79. Voshall had nine cases -- foreclosed and vacant houses -- on the half-mile-long street.

“This is my newest house,” she said, pulling to the end of a cul-de-sac. She paused, staring at the house next to that one. It too was now abandoned, its lawn dead and its baby trees withering in the sun. Make that 10 cases on Kingston.

There was no “for sale” sign, no eviction notice. Someone simply walked away. She rang the doorbell, then left behind a document explaining that the lawn would still need to be maintained.

“This neighborhood is lovely,” she said, shaking her head and walking back to her truck. “It gets to you after a while. All of these families . . . where did they all go?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.