L.A.’s street signs have been at the intersection of time and place

- Share via

The story of Los Angeles’ street signs is hidden safely away on the ninth floor of Caltrans’ downtown headquarters:

Hand-stenciled wooden two-by-fours like those that originated in the 1890s, their white block lettering set against a dark blue background. The shotgun-style placards first erected in the 1940s. The blade style that surfaced in the ‘60s.

Ten different designs have popped up over the decades on the corner poles and posts marking Los Angeles’ 40,000 intersections.

And the biggest fan of those 178,000 or so street name signs is John Fisher, who retired two years ago after 39 years as a city Department of Transportation engineer and assistant general manager.

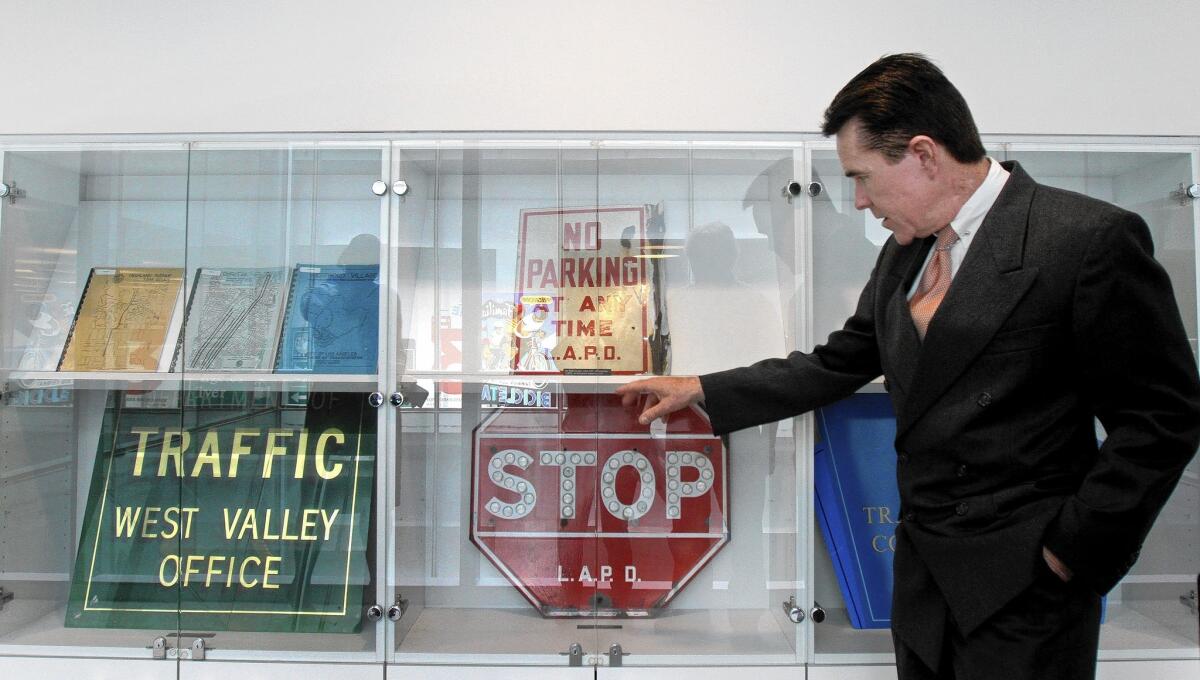

Fisher, 66, of South Pasadena, amassed a collection of the designs and donated them for display. Eight are hanging in frames on a conference room wall. More signs and other historic transportation documents are displayed in glass cases in a nearby hallway.

“This one is my favorite,” said Fisher, pointing to a porcelain shotgun-style marker salvaged from the 800 block of North Alameda Street.

“This was in front of Union Station near Los Angeles Street, and is in the style used roughly between 1938 and 1940. It has filigree work on the top, and the bottom is dropped in the center. It was a very attractive sign.”

Fisher said the filigree metalwork — also used on signs during the late ‘20s — “was kind of reflective of the Jazz Era and the Art Deco period.”

It was the inspiration, Fisher said, for the newer signs like the one outside the Caltrans building at 1st and Main streets. The block number is on the rounded center portion, at the bottom, and the city seal is displayed up top. Those signs began appearing in 2010.

Because of budget concerns, the seal-clad signs are installed only when developments prompt the redesign or widening of a street, said city transportation engineer John Sam. They cost about $100 apiece.

According to Fisher, Los Angeles’ first street sign style — the wooden board variety — was in use until the start of World War II.

“They were installed at first on all streets … [but] in time they were used only on residential streets,” he said. “Porcelain enamel signs were used in more of the urban area’s main thoroughfares.”

His collection includes a wooden sign for Encino Avenue that he figures was installed in 1940 and used until the 1990s.

The oldest sign in Fisher’s collection is an Auto Club marker that was erected in front of the Beverly Wilshire Hotel in 1925. It pointed the way to Los Angeles (71/2 miles), Santa Monica (81/2 miles in the opposite direction) and Venice (11 miles.)

“I got it in the ‘70s for $100, from an old traffic engineer. … It is typical of what the Auto Club had all over Southern California,” he said. “They installed signs before jurisdictions did, or Caltrans, which used to be the Division of Highways.”

In the 1920s, the city switched to metal signs — blade-shaped porcelain enamel with white lettering on a blue background.

Fisher’s display includes a trapezoidal sign for Golden Avenue that was installed in the late 1920s. Above it is a sign salvaged from Missouri Avenue that features an elongated bottom.

“I’ve heard it called two names: the ‘bird nest sign,’ because we’d find many birds’ nests between the two panels … [and] the ‘shotgun sign’ because of its shape.” Fisher said. That style, which went up all over the city between 1946 and 1962, “reflected the technology of the times.”

But that particular variety came in one size only, which meant the city had to squish together lettering for longer street names such as “Mississippi” or “Santa Monica,” he said. Manufacturers began phasing out the porcelain signs in favor of metal ones because the enamel paint emitted fumes when baked and lacked the necessary reflective qualities mandated under federal rules.

Fisher’s collection includes a Maple Avenue sign that was embedded in a concrete curb face in 1925. It was salvaged in 1990, when Washington Boulevard was widened for construction of the Metro Blue Line. There’s also an early 1970s Ord Street sign printed in English as well as Chinese.

In his garage at home, Fisher has kept a selection of old signs for himself, including some antique U.S. route shields from the 1930s. But his best are on view at the Department of Transportation.

“I wanted to make sure we had a permanent display here,” he said. “I was very attached to the department, and thought that maintaining its legacy and heritage and history was important.”

Twitter: @BobsLAtimes

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.