Why have lieutenant governors?

- Share via

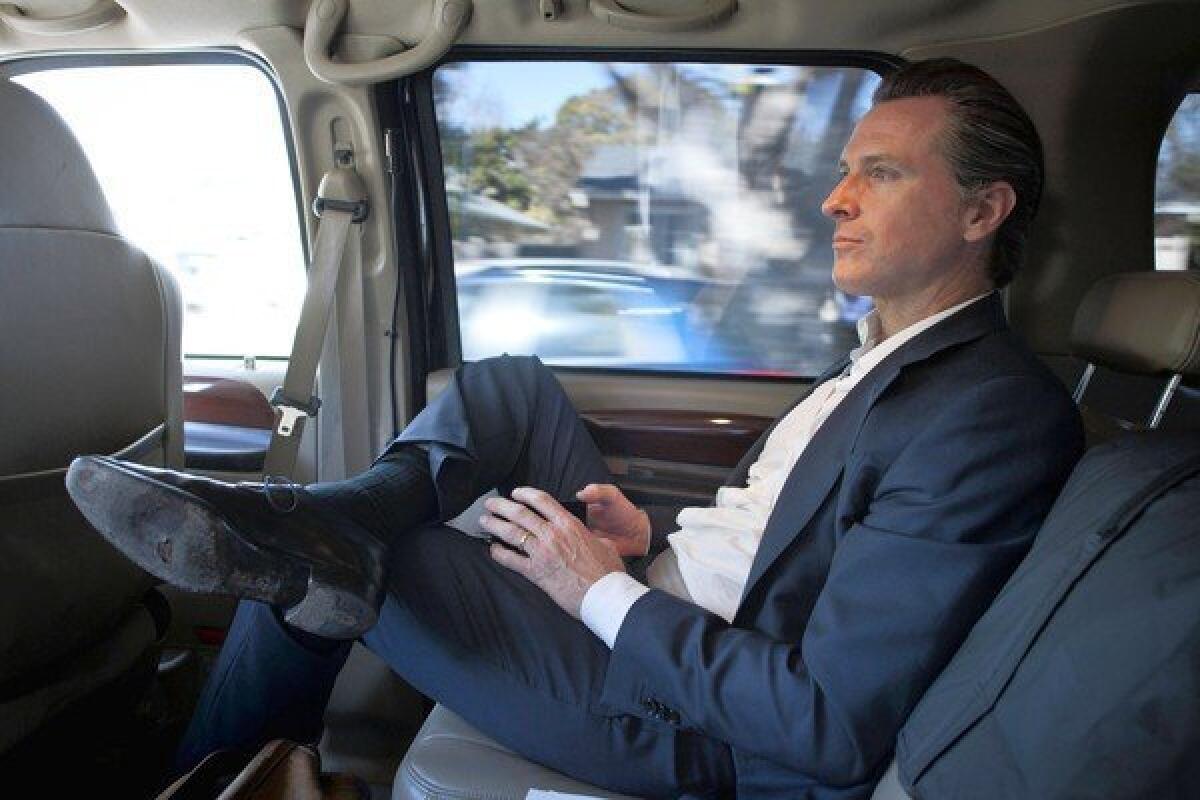

You could say that Gov. Jerry Brown treats Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom like a dog. But that wouldn’t be accurate.

Brown’s Pembroke Welsh corgi gets invited into the governor’s office practically every day. Sutter gets lots of petting. He regularly walks with gubernatorial aides in Capitol Park.

Newsom essentially gets locked out.

Such is the plight of most California lieutenant governors.

But you’d think that Newsom would be treated better, given the past bonding between his and Brown’s families.

Newsom’s grandfather was a close friend and campaign strategist for Brown’s father, Gov. Pat Brown. He also was the godfather of Kathleen Brown, Jerry’s sister. Jerry Brown, the last time he was governor, made Newsom’s father an appellate court judge.

“Jerry helped me with my application to Santa Clara” University, recalls Newsom, 45.

But personal relationships are not the 75-year-old governor’s specialty. Charm, when it suits. Warmth, no.

Still, Newsom isn’t complaining, at least out loud.

“I get it,” he says.

Newsom — then the San Francisco mayor — initially challenged Brown for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 2010. “I stayed in that race a little longer than he expected or wanted,” Newsom says. “So I’m not naive.”

After he was elected lieutenant governor, Newsom continues, “it was obvious pretty quickly that this wasn’t going to be as easy and seamless as I had hoped.”

Newsom told me, in good humor, “You triggered this” by writing a column two years ago praising his authorship of an economic growth plan for California. “It was the kiss of death.”

Brown felt that Newsom was trying to upstage him.

The lieutenant governor now concedes that “we got ahead of ourselves on an issue that was not his first priority.”

Brown’s top priority then was to return state government to solvency. “He’s done a magnificent job on that issue,” Newsom says. “Trust me, I wouldn’t say that if I didn’t believe it. I admire the hell out of him.”

But Newsom apparently hasn’t had a chance to tell Brown that personally.

“I’m ready to take the call and be supportive, whatever he needs,” Newsom says. “I really do want to rekindle a relationship, but it’s his prerogative.”

All this political strain between two Democrats came to mind last week as Newsom assumed the role of acting governor while Brown flew off to Ireland and Germany searching for family roots.

Except that “acting governor” really is a misnomer. Despite the California Constitution’s edict that the lieutenant governor “shall act as governor during [the real one’s] absence from the state,” it hardly ever works that way, particularly in recent years.

The actual acting governor is Brown’s executive secretary, Nancy McFadden. She has been updating Newsom, especially on prison turmoil, but he isn’t making any meaningful decisions.

All of which begs the question: Why do we even have the office of lieutenant governor? We certainly don’t need it.

We don’t travel by horse and buggy anymore. A governor can stay in contact with the Capitol from virtually anywhere on Earth.

If a governor quits or is incapacitated, another elected state official could succeed him. That’s what six other states do.

California’s lieutenant governor is a voting member of the UC Board of Regents and state university trustees. That’s the job highlight.

He’s also ostensibly president of the state Senate — and can vote if there’s a 20-20 tie — but got booted off the chamber floor this year because there was nothing for him to do officially. He also chairs the state economic development commission, but it can’t vote because Brown hasn’t filled enough vacancies.

So lieutenant governor is pretty much a nothing job.

There was one occasion decades ago, when Gov. Jerry Brown was off running for president, that a lieutenant governor tried to act and looked foolish. Republican Mike Curb nominated an appellate judge and was forever ridiculed as a troublemaker. Brown quickly flew home and withdrew the nomination.

Newsom won’t be “doing anything crazy,” he vows. “Our relationship is not even close to a place where Jerry needs to worry about leaving the state.”

But for whatever reason — vindictiveness, paranoia, politics, bullying—lieutenant governors often have needed to worry about governors.

Republican Gov. Pete Wilson tried to kick Democratic Lt. Gov. Gray Davis out of the Capitol.

Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger slashed Democratic Lt. Gov. John Garamendi’s budget by 70%.

Newsom’s budget is down to less than $1 million. That’s enough for 3 1/2 employees.

Just dump the whole office. Why bother?

“I think it can have an important purpose,” Newsom responds. “It can be the eyes and ears for the governor on higher ed, economic development, delta water....”

We don’t need a lieutenant governor for that.

But politicians like the office because they think it can be a launching pad for governor. Davis used it that way, and Newsom hopes to in 2018.

It can also provide a landing spot for termed-out legislators.

Or politicians can create a phony lieutenant governor campaign committee to stash political funds — as Senate leader Darrell Steinberg (D-Sacramento), Assembly Speaker John A. Pérez (D-Los Angeles) and retiring Treasurer Bill Lockyer all have done for 2018.

Newsom wants to amend the Constitution to require the governor and lieutenant governor to run as a ticket, a la the president and vice president. About half the states do that.

This could create some loyalty and cooperation between the running mates once they’re elected. That would be a vast improvement.

But Newsom couldn’t find a legislator willing to carry the bill.

Vice President John Nance Garner — FDR’s veep — famously said his job was “not worth a pitcher of warm spit.”

If so, Newsom’s isn’t worth a dog puddle.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.