Yosemite visitors reflect on deadly mistakes along a fabled trail

- Share via

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK — The two sisters boarded the morning bus to the Happy Isles trail head, ice cream cones in hand.

For 50 years, their tradition has been to start a day on Mist Trail with some mint chocolate chip.

Before they left on this year’s trip, friends told Patty Frehler, 67, and Suzanne Barovick, 66, “Don’t go over the falls.” And they weren’t entirely joking.

On June 1, Aleh Kalman, 19, was swimming above Nevada Fall and the current carried him over the precipice. Last August, 6- and 10-year-old brothers were swept downriver below Vernal Fall. The year before, the river carried three young people over the top of 317-foot Vernal as a crowd of helpless picnickers watched in horror.

At least 14 people have gone over falls along the Mist Trail in the last 10 years. None survived.

Three days after the latest death, the line between adventure and foolishness, and whether the National Park Service should do more to protect people from making deadly mistakes, was on the minds of many people on the fabled trail.

“We’ve been coming to Yosemite since I was 18 and back then I don’t think we ever heard of a death,” Frehler said. “Nothing’s really changed. Same mountains. Same river. So, why are so many more people dying?”

Frehler considered the first stretch of shady, paved path, where the Merced River bubbled beside a stone wall.

“It looks innocent. Maybe they need bigger warning signs,” she said.

Her husband, Bob Bentley, strongly disagreed.

“They have more precautions now and they haven’t done any good. It’s like air bags in cars — people just drive faster,” he said.

Less than a mile into the hike, the first bridge offered a jaw-dropping glimpse of Vernal Fall in the distance. Bob Heath, 83, held hands with Evelyn Treadgold, 84, and looked at a view he hadn’t seen since 1951.

When Heath was fighting fires in the park, he’d go on all-day hikes. He didn’t always exercise caution, he conceded, “But, I’ll tell you what, I never went swimming above a waterfall.”

Glacier-cold water flowed under the bridge. In some spots it looked deceptively calm with clear pools revealing every pebble.

A boy about 8 years old stood on a large boulder in the river. It was near where the young brothers, on an extended family outing, went for a swim last summer and were immediately swept downriver.

“You can’t save someone who falls in this river. If you try, you’ll die too. It’s granite. It’s wet,” said Doug Chavez, 42, with a hint of anger even after the boy had rock-hopped back to shore.

On the day Kalman went over the fall, Chavez, a San Francisco Outward Bound instructor, had been hiking with his nieces and nephews in Yosemite Valley. He heard the helicopters.

“I didn’t even know what had happened, but I told the kids, ‘Someone just died.’ I wanted to scare the crap out of them,” he said. “Especially my nephew. He’s 8 and he keeps…” — he interrupted himself to yell — “Andrew! Get down! That rock is too close to the water.”

At the end of the bridge, the Park Service had posted a bright yellow warning: “Stay back from moving water.”

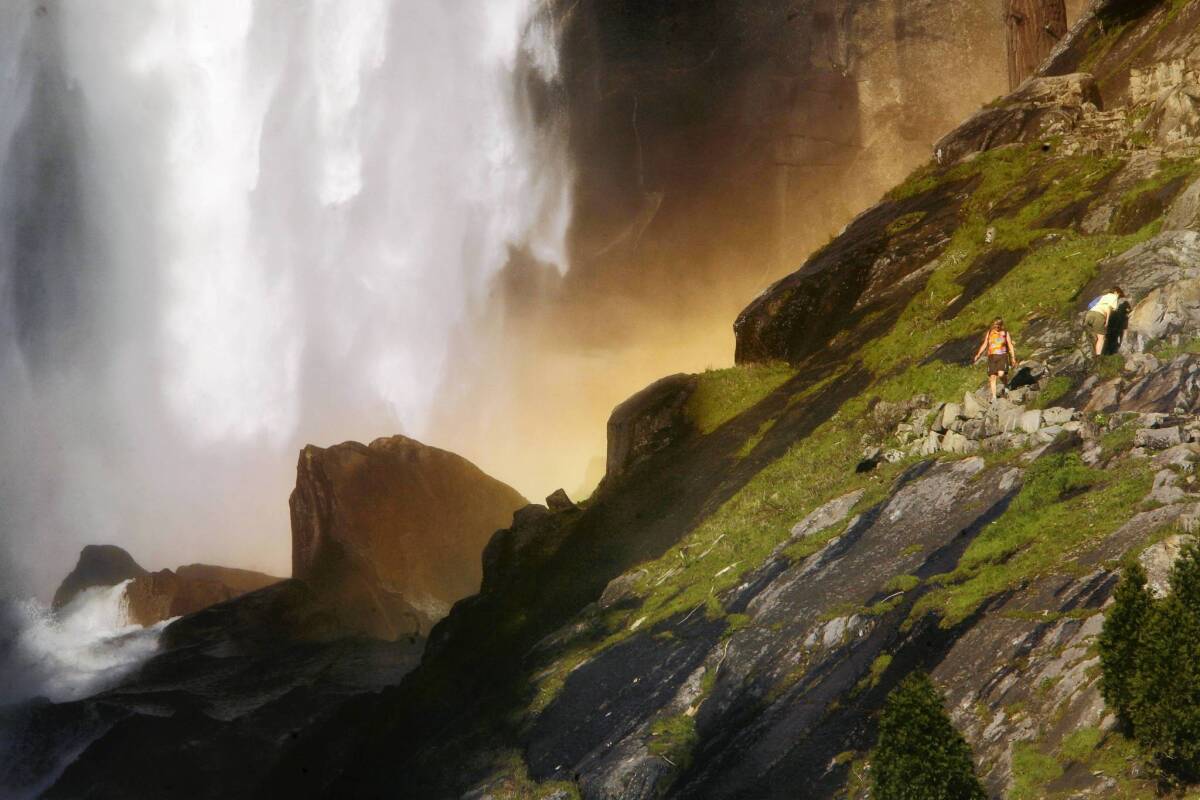

Soon the trail became a staircase blasted out of granite. Irregular steps, many of them three feet high, climbed alongside the fall. Big clouds of mist floated over, drenching hikers as thoroughly as a log ride at an amusement park.

The staircase changed direction and crossed to the granite expanse above Vernal Fall — one of Yosemite’s most popular spots. A summer day can see 2,000 visitors.

A jovial group took turns posing for pictures in the corner of a guard rail in front of the fall. In the 2011 tragedy, two people in a church party — first-time visitors — stepped over the rail to pose for a photo. One slipped. Both fell. Another friend tried to save them. All three died.

On previous visits, Edward and Shanti Johnson, dancers with the Southern California Dance Theater in Long Beach, posed in the popular corner. But on this day, with baby daughter Makhana, they took their vacation photo yards away in the center of dry rock.

“We talked about how more people have died on this trail than any other in the park,” said Shanti, 37. “And when I showed Makhana the river — I know she’s only 7 months old, she can’t understand me but, still, — I told her ‘Beautiful water. Look at the pretty water. But remember we stay behind the rail.’ ”

A few yards away, Alex Rodriguez, 21, sat with a church group from Van Nuys. Many were trembling and exhausted; one girl was in tears. Rodriguez looked entranced, gazing at the river.

“At first I didn’t feel like I was supposed to be here. It kind of felt like no one was supposed to be here. But after a while you get used to it,” he said.

He said the water looked tempting, but he would never consider swimming.

“I’m not stupid,” he said. “It’s like common sense.”

Though four of the recent deaths have been from city church groups, Pride Metcalf, one of this group’s leaders, said it was good to introduce young people who had never been out of the suburbs to nature.

“Look, they live in neighborhoods with drive-bys. Their world can be rather small. We bring them up to these vistas to show them they have options,” he said. “And we tell them in graphic detail what can happen when you don’t follow rules in the wilderness.”

For the bulk of the crowd, the top of Vernal was as far as they would go. But the trail led on, past Emerald Pool on the “step” between two waterfalls. The Park Service strongly advises visitors against even wading in this spot, yet on a hot day some swimmers still take their chances against the current.

On a universal “No Swimming” sign — a swimmer inside a circle with a line slashed across him — someone had tried to rub out the slash.

When Nevada Fall came into view, its plumes seemed to freeze-frame in bright white clouds. The water free-falls for the first third of the way before hitting a ledge and billowing up, like a snowy avalanche.

On the day Kalman died, a joint group of three Slavic churches, some 85 people, were relaxing near a footbridge about 150 feet above the fall, according to authorities.

Kalman was on a boulder in the river with another swimmer. The two jumped in to swim back. One made it; Kalman didn’t.

On this day, two National Park Service employees were moving quickly down the trail, dodging hikers. When tourists asked them what they were doing, their stock answer was “preventative safety measures.”

It isn’t their job to police the river. One said he didn’t think it should be.

“How do you decide what is safe for who and when?” he asked. “This is wilderness and people are free to make their own choices.”

He moved down the mountain on his real task — searching for Kalman’s body.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.