Feds say ‘Shrimp Boy’ claim of outrageous government conduct lacks merit

- Share via

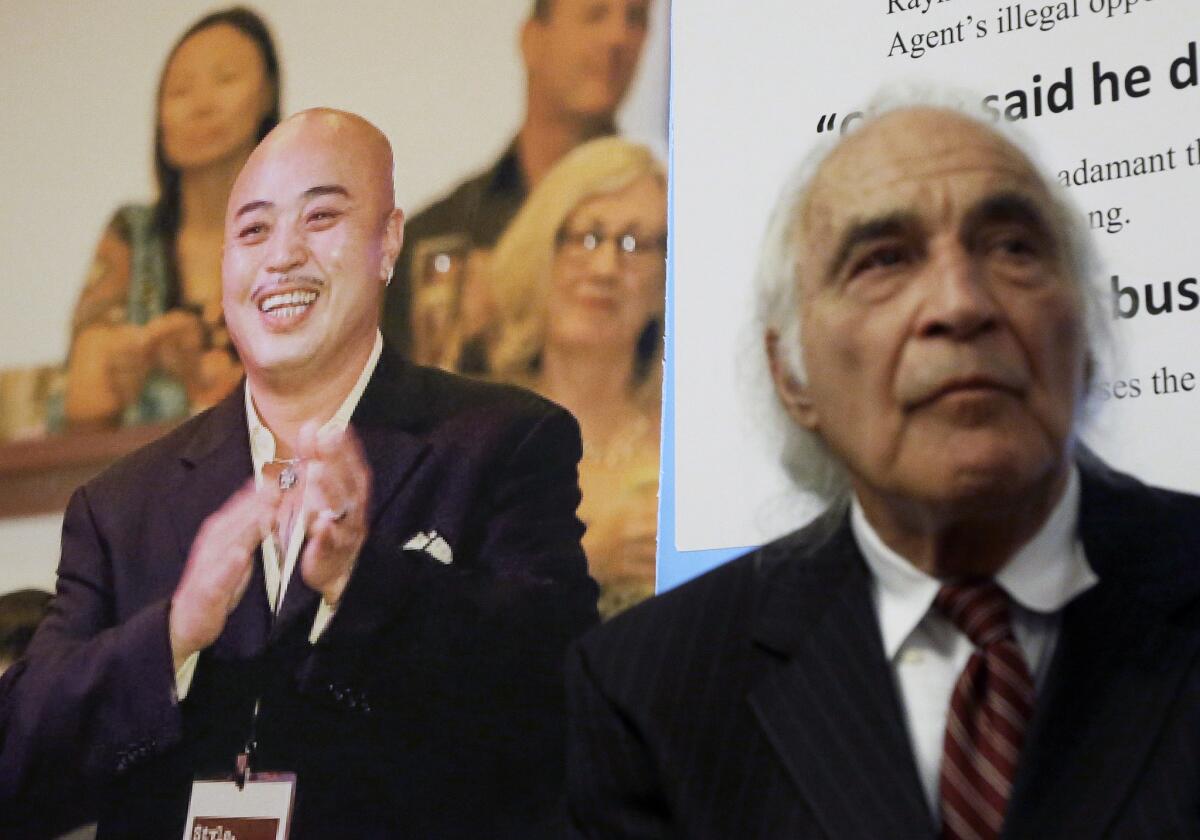

Reporting from San Francisco — U.S. District Judge Charles R. Breyer declined to rule Monday on a motion by Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow’s attorneys seeking dismissal of the sweeping racketeering case against him due to “outrageous government conduct.”

While such motions are typically heard before trial, the jury is now hearing its second week of testimony in the high-profile case. As a result, Breyer said he would wait and issue a ruling on the motion only if jurors issue a guilty verdict.

Earlier in the morning, the U.S. attorney had filed a motion opposing Chow’s “eleventh-hour” push for dismissal, saying it lacked legal merit.

Chow, “dragonhead” of the Chinatown fraternal organization known as the Ghee Kung Tong, is charged in a sweeping racketeering case that led in July to a guilty plea by former state Sen. Leland Yee. The case against Chow alleges he feigned innocence while leading a criminal faction of associates who joined an undercover agent in money laundering, and trafficking in stolen liquor and contraband cigarettes.

Counts added to the indictment last month say he also arranged the murder of his Chee Kung Tong predecessor and conspired to have another gang rival killed.

But on Nov. 4, with jurors already selected, Chow’s attorneys filed a motion to dismiss, contending that the conduct of the main undercover agent -- known as “David Jordan” -- was so outrageous that the U.S. District Judge Charles R. Breyer should toss the case.

The government, they said, provided all the money and ideas for the illegal acts, which defense attorneys maintain Chow did not commit (he repeatedly told Jordan he had gone straight, they note), and often got Chow drunk before pressing envelopes of cash into his hands as he vocally resisted.

“Outrageous government conduct” is related to the legal defense of entrapment, which experts say is almost impossible to pursue in federal court because the defense must show that the defendant had no criminal predispositions. Chow has a copious criminal record but steadfastly maintains he is reformed.

Outrageous government conduct is not a defense. Such a claim, however, allows a judge to dismiss indictments or order acquittals in rare cases where government actions violate due process.

In their response Monday to Chow’s motion, prosecutors maintain that he has not come close to meeting the standard of proof that the government conduct was “so grossly shocking and so outrageous as to violate the universal sense of justice.”

Citing a U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruling from 2011, prosecutors said there are just two reported decisions in which federal appellate courts have reversed convictions under the outrageous government conduct doctrine.

Creating and directing a criminal enterprise “from start to finish,” or using “excessive physical or mental coercion” to lure a defendant into committing a crime would meet the standard, they wrote, quoting the earlier ruling. But, they added, “it is not outrageous to infiltrate a criminal organization, approach individuals who are already involved in or contemplating a criminal act, or provide necessary items to a conspiracy.”

Chow was already on the radar of federal law enforcement before the multi-year probe began, prosecutors said.

The FBI in 2005 received information -- though unsubstantiated -- that he was involved in Chinatown’s criminal underworld and withdrew its support for an informant visa that had been promised to him based on his cooperation in a previous case, prosecutors said.

A career criminal, he was also “fully aware that his associates were actively involved in criminal activity on behalf of the [G]hee Kung Tong and Hop Sing Tong, rather than naively being merely present” as the agent dealt with those associates, prosecutors wrote.

While the government -- mostly through “David Jordan” -- created criminal opportunities in the beginning of the investigation to gain trust and access to the criminal crew, soon “Chow and his associates described their own criminal activities and eventually brought opportunities to the undercover agents,” prosecutors said,

Furthermore, they said, the undercover agent had nothing to do with the murder-for-hire aspect of the case.

The government proposed the crimes of reverse money laundering and trafficking in alcohol and cigarettes because those caused “no societal harm” and the government could not participate in the schemes proposed by the defendants, such as “providing narcotics or ... transporting narcotics,” they wrote.

“This was not an outrageous investigation,” they concluded. “What was outrageous was the number of criminal actors who followed Chow, surrounded and supported him on a daily basis, and who flocked to the invitation to engage in criminal activity once Chow proclaimed the undercover agents to be ‘good and loyal brothers’ for whom Chow professed love.”

Breyer’s courtroom is expected to be closed to the public all week as undercover agents who are actively working cases take the stand, though media and some observers are permitted to observe the videotaped proceeding from an overflow room.

On Monday, however, a juror fell ill and testimony was postponed for the day.

Twitter: @leeromney

ALSO

As huge El Niño brews, California fights to keep drought mentality

Oakland police fatally shoot man who allegedly pointed replica gun

Rocket kills man when it hits him in the face at Scouting event

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.