Unlikely friendship leads to Carlsbad man’s exoneration after 38 years in prison

- Share via

In 1978, Simi Valley was a small, quiet and safe bedroom community, thanks to many regional police officers who called it home.

Michael Bender was a teenager in 1969 when his family moved to the small city, which back then was so remote it had no freeway access.

Craig Richard Coley arrived in Simi Valley two years later. He was 23, the son of a retired L.A. police officer, a Vietnam veteran and a newly married man with no criminal record. Over the years, he managed several restaurants, including a Howard Johnson’s and a Rustler’s steakhouse.

After a divorce, Coley dated for a time Rhonda Wicht, a 24-year-old waitress and cosmetology student who shared an apartment with her 4-year-old son, Donald.

Meanwhile, Bender had started a police career in 1977, first working the streets of South Los Angeles for 18 months before landing a patrol officer job back in Simi Valley in October 1978.

A few weeks later, Wicht and her son would be killed in their beds, changing the trajectory of both Coley’s and Bender’s lives, though their paths wouldn’t cross for another 13 years.

Just hours after the bodies of Wicht and her son were discovered Nov. 11, 1978, Coley, a former boyfriend, was arrested and later charged with the murders. After two trials, he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

That might have been the end of the story for Coley if not for the relentless efforts of Bender, a former Simi Valley police detective who spent nearly 30 years fighting to prove Coley’s innocence.

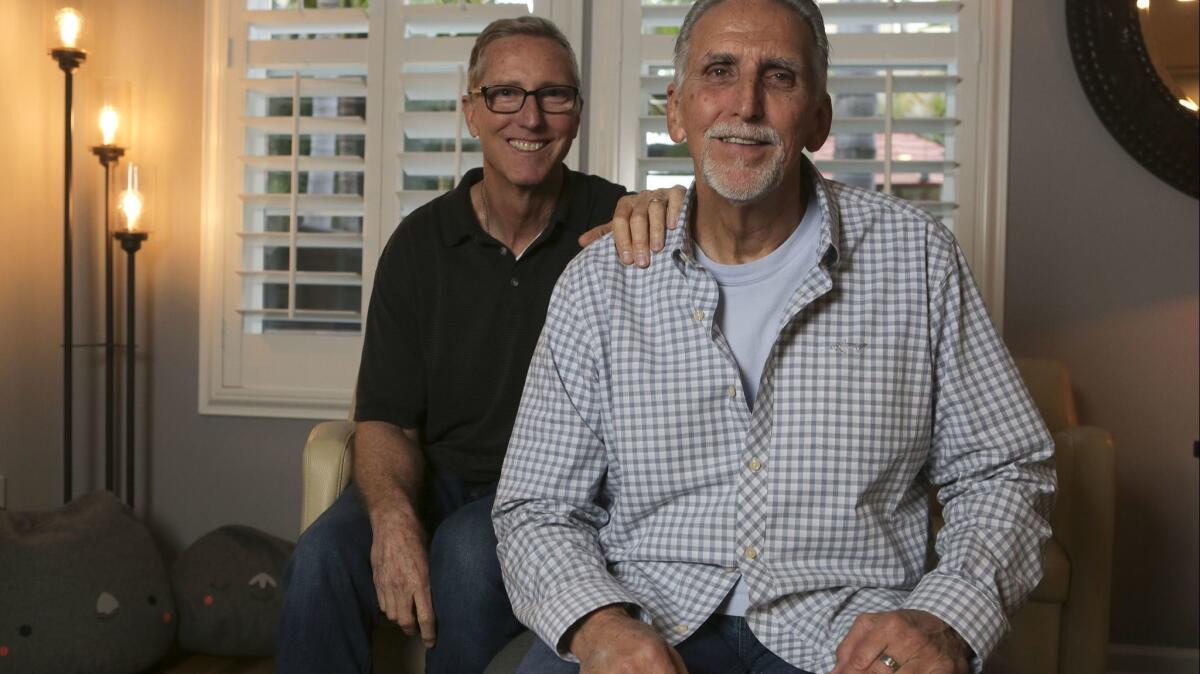

Last November, citing new DNA and investigative evidence, Gov. Jerry Brown exonerated Coley, clearing his record and freeing him after nearly 39 years in prison. Since then, Coley has been quietly living in Carlsbad with Bender and his wife, Cynthia, as he slowly starts his life over at age 70.

Coley calls Bender his tireless “savior” who was sent by God to help set him free. But Bender, 62, said he was only doing what all good cops strive to do: help others.

“I always believed in truth, integrity and honor,” Bender said. “I’m glad this story has a happy ending. If I was on my deathbed knowing he was still in prison, I would have had a hard time with that.”

‘A miscarriage of justice’

On that November morning 40 years ago, Wicht was scheduled to style the hair of the bridal party for a girlfriend’s wedding. But when she didn’t show up, a friend went to check on her and found the bodies. Wicht had been strangled, likely with a macrame rope, and her son was found smothered in his bed.

Coley, who had recently gone through a breakup with Wicht, heard the news and called the police to learn more. By the end of the day, he was under arrest, suspected of the crimes. Police described Coley as an unhappy ex who still had a key to Wicht’s apartment, which had no sign of forced entry when police arrived.

His first trial ended in April 1979 in a hung jury, with 10 to 2 in favor of conviction. A second trial in January 1980 ended with his conviction on two counts of first-degree murder with special circumstances.

Simi Valley residents who had known Coley signed petitions to have the verdict reexamined. Newspaper headlines championed his innocence, and the judge in the first trial called his conviction a miscarriage of justice.

Coley’s parents, Margie and Wilson Coley of Sherman Oaks, emptied their retirement accounts and mortgaged their house to hire new attorneys and investigators for their only child.

But all hope was lost when his conviction was affirmed in a state appeals court.

Four decades later, Coley still doesn’t like to talk about the killings, not just because of his wrongful conviction but because he cared deeply for the victims.

“It’s not something you can describe other than it’s painful,” he said. “I went four decades not being able to grieve the woman and child I loved.”

Red flags in the case

Bender wasn’t involved in the Wicht investigation and had no real memory of the case until 1989, when he had worked his way up to the rank of detective at the Simi Valley Police Department. A friend suggested he take a look at Coley’s case file, and he was shocked by the red flags he saw.

Coley had a solid alibi for all but 20 minutes the night of the killings, and the crimes would’ve have taken much longer than that to commit. There were viable suspects who were never pursued, and hair and fingerprint evidence that wasn’t analyzed properly and then went missing.

“It appeared,” Bender said, “that a real investigation hadn’t occurred.”

Around 1991, Bender went to meet Coley at a state prison in Tehachapi and said he knew on instinct he was talking to an innocent man.

“In dealing with a lot of bad guys over the years, there are mannerisms and body language you come to know. He didn’t have that,” Bender said.

Promising to do what he could to get the case reopened, Bender collected 16 boxes of case files from Margie Coley, whose husband died in 1988.

But nobody wanted to listen, especially his supervising lieutenant, who had been in charge of the original murder investigation. Bender took the case to the city manager, the city attorney, a local congressman and eventually the attorney general, the American Civil Liberties Union and the FBI.

In 1991, he was ordered by his supervisors to stop pushing the case or face termination. Disillusioned, he quit his job and left Simi Valley for good, taking the 16 boxes with him and vowing never to give up.

Coley said he did his best to maintain hope as the years stretched on and he was moved from one prison to another. At Folsom prison, he learned to make jewelry from a fellow lifer and sent the money from jail gift shop sales to his mom to hire investigators.

He exchanged a lot of letters with friends and family. And every Saturday, he talked by phone with Bender, who often visited the prison with his daughter Mikali Bender or with Margie Coley.

Some prison stretches were harder than others, particularly at the ultra-violent Folsom, but the soft-spoken Coley was a model prisoner who helped run a veterans support program and mentored others.

“How did I keep my spirits up? Sometimes I didn’t,” Coley said. “I had good days and bad days. I always knew there was someone out there who did it and they’re not looking for him. That was really hard.”

Never giving up

Around 2005, Coley said, he began actively practicing his Christian faith, which helped him “cut out all the nonsense” in his life. He started a prison Bible study group in 2011 and later earned degrees in theology, biblical studies and biblical counseling.

“My way of looking at things changed,” he said. “I believed whatever happened was what God had in store for me, and everything I get is a blessing.”

When Bender left Simi Valley in 1991, he moved to Northern California to work as an investigator for the National Automobile Theft Bureau. Ever since, he’s worked in theft investigations, most recently with ICW Group, where he’s national director of special investigations.

In 2003, he moved to Carlsbad with Cynthia, whom he first met in Simi Valley in the mid-1980s. By coincidence, she was an invited guest at the wedding where Wicht never showed up.

Cynthia said her husband never flagged in his quest to get the Coley case reexamined. He would frequently get up at 4:30 a.m. on weekdays to put in a couple of hours of work on the files before heading to the office.

The tide finally began to turn in September 2015, when Brown’s office agreed to conduct an investigation. Then in 2016, Bender met new Simi Valley Police Chief David Livingstone, who started his own investigation with the Ventura County district attorney’s office.

DNA evidence, previously thought destroyed, was found and tested, revealing another man’s sperm, blood and skin cells on sheets and clothing in the apartment. Witness testimony also was largely discredited.

On Nov. 20, 2017, Livingstone and the district attorney filed a clemency petition. Brown signed the pardon two days later. An investigation is underway to find the Wichts’ real killer, and an internal probe is being conducted into allegations of the mishandling of the original case in Simi Valley.

‘Joy, just pure joy’

Coley said he knew through Bender that a pardon was coming, but he wasn’t prepared for the Nov. 22 call from the governor’s office at his prison in Lancaster.

“You dream about it, you hope for it, but when it happens, it’s a shock,” he said. “To experience it was something I never thought would feel as good. It was joy, just pure joy. I got all tingly in my stomach, and then I was bawling like a baby for a while.”

After getting hugs from his fellow inmates, a plastic bag of clothes and a $200 debit card, Coley was driven to the Benders’ home, arriving at 9:30 p.m. on the eve of Thanksgiving.

His first taste of freedom was two stops on the way down, first at an In-N-Out to savor a burger, fries and shake, then his first-ever visit to a Starbucks, for a caramel macchiato with a double shot of espresso.

There was never any question that Coley would make Carlsbad his home once he was freed. When his mom became ill in 2004, the Benders moved her to Carlsbad, where Mikali Bender helped care for her until her death in 2011. Bender’s family became Coley’s family.

Coley has been staying in the Benders’ home ever since.

“Now that he’s here, I can’t imagine him being anywhere else,” Cynthia said. “He’s so courteous and kind and the best house guest anyone could ever ask for. He has always been a part of our family.”

Coley was 31 when he entered prison. When he emerged, he had no savings, no photo ID, no driver’s license, no credit rating and no possessions.

For the first month or so, Bender said, Coley wouldn’t leave their gated community for fear of getting stopped by police. But since he got his ID and a driver’s license, he’s now enjoying going for solo drives in his new red Jeep Grand Cherokee and chatting on his first cellphone.

Cynthia cares for the Benders’ 3-year-old granddaughter, Keira, in their home, and Coley said watching her play and dance gives him endless amusement. Cynthia said Coley’s unfamiliarity with the outside world puts him at the same level of social and technological development as Keira.

“I call Keira my ‘little,’ and he’s my ‘big,’ ” she said. “In December, I took them both to see Santa.”

13,991 days behind bars

In February, the California Victim Compensation Board voted unanimously to award Coley $1.9 million, $140 for each of the 13,991 days he served behind bars. It’s the highest award ever paid to an exonerated California prisoner.

Coley said the money — which he should receive in August — is a comfort for his old age but will never make up for what he has lost.

“It helps, but how can you put a price on 40 years of your life?” he said.

To tide him over until then, Coley has been living off a Gofundme account (“Fundraiser for Craig Coley Free At Last”) that Bender set up last fall. It has raised more than $73,000.

Coley spent much of the money on a down payment for an older home in Carlsbad, just a couple miles east of the Benders’. He’s also doing some traveling. He’ll spend his 71st birthday on June 7 in Hawaii. He also wants to buy himself a dog, maybe a Sheltie or Australian shepherd.

But when asked what he savors most about his freedom these days, Coley says it’s the little things.

“What I love is being able to get up in the middle of the night to get a cold drink of water from the refrigerator, or standing out on the porch at night to look up at the stars,” he said. “These are things I never appreciated so much until now.”

Kragen writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.