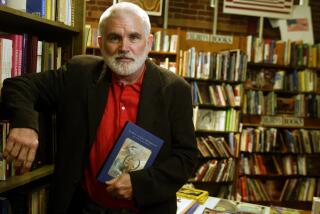

Eric Harris Davidson dies at 78; pioneering developmental biologist

- Share via

Eric Harris Davidson, a developmental biologist whose work revealed how complex organisms arise from the meeting of egg and sperm, has died at 78.

Davidson, who was Norman Chandler professor of cell biology at Caltech, died Sept. 1 after a heart attack, said his daughter, Elsa Davidson.

In 1969 and 1971, Davidson coauthored papers that sketched, for the first time, the process by which networks of genes interact to drive embryonic growth, the proliferation of specialized cells, and the creation of organisms of vastly diverse shapes and sizes.

Two decades before the Human Genome Project would be launched, Davidson and his longtime collaborator, molecular biophysicist Roy Britten, proposed models of gene regulation that would presage much later work on the epigenome — the system of molecular marks that turn genes on and off and regulate their production of proteins to build different types of tissue.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

The two concluded that networks of interacting genes define how an animal’s body plan will (and will not) take shape, emerging from a pair of undifferentiated cells. And they suggested that small changes in the function of these regulatory networks could be a key engine of evolutionary change.

Their work became a cornerstone of the field of evolutionary developmental biology.

“He was a revolutionary,” said Ellen V. Rothenberg, a Caltech stem cell biologist who was Davidson’s companion and scientific collaborator for more than two decades.

“In the 1950s and ‘60s, this was a fusty, stodgy field” in which scientists collected, categorized and described organisms, Rothenberg said. “He came in and dragged them into the genomic age.”

Drawing on his familiarity with “every kind of obscure invertebrate,” Davidson was determined to understand how different patterns and interactions of DNA — a molecule common to virtually all forms of life — could produce such an astonishing diversity of creatures, Rothenberg said. He was an ardent animal lover, and had to be persuaded not to feed the black bears that occasionally wandered into the yard of his home in Pasadena’s Kinneloa Canyon.

Davidson could be “quite blunt” in his disagreements with colleagues, Rothenberg said. And he was impatient with scientists who lacked his impulse to look for the bigger picture — how genetic and molecular processes give rise to an array of cells, how those cells give rise to distinct systems, how those systems come together to create such different organisms, and how those organisms give rise to so many species.

“He was a cathedral builder,” she said.

Over the last 40 years, Davidson’s work centered on the purple sea urchin, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, whose range includes the waters off Caltech’s Kerckhoff Marine Biology Laboratory in Corona del Mar. The sea urchin reproduces prolifically, and its embryos — just a single cell layer thick — afforded Davidson a clear window for watching its genetic machinery at work.

Unlike animal models widely used in cell biology — the fruit fly drosophila, or the nematode C. elegans — the purple sea urchin hails from the same branch of the evolutionary tree that gave rise to humans. His insights were therefore likely to shed particular light on human biology as well.

Davidson’s work touched early on some of genetic science’s current controversies. Some of the genetic material he identified as key to building a sea urchin’s spiky body was located in the midst of repeated DNA sequences that hold no blueprint for the production of a protein. Scientists long dismissed those long strings of seeming genetic gibberish as “junk DNA.” Davidson’s research was among the first to suggest otherwise — a view that has increasingly taken hold.

Davidson was also an early adopter of genetic editing — a practice whose potential application in human embryos has sparked impassioned ethical debate. In a bid to devise a computational model of genetic regulation in the purple sea urchin, Davidson tinkered extensively with those processes, inserting foreign and engineered genetic material into sea urchin embryos.

“Eric’s early recognition that ‘biological engineering’ would be a powerful approach for elucidating fundamental biological principles is an excellent example of his ability to foresee important advances in science,” said Caltech biochemist Stephen Mayo, who chairs the university’s division of biology and biological engineering.

Davidson’s daughter, Elsa, of New York City, described him as a “great storyteller” with a wide-ranging intellect.

In addition to authoring six books, Davidson was among the founding members of the Iron Mountain String Band, which played and recorded traditional songs of Appalachia. Davidson played the clawhammer banjo.

He read history avidly, and named his beloved Persian cats after ancient historical figures, she said. He loved gardening.

Davidson was born April 13, 1937, in New York City. He earned his bachelor of arts degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1958 and his doctorate from Rockefeller University in 1963.

After working as a postdoctoral researcher and then as a member of the Rockefeller faculty, he arrived at Caltech as a visiting assistant professor of biology in 1970. He joined the faculty in 1971 and was named Chandler Professor in 1982. His honors include membership in the National Academy of Sciences and the International Prize for Biology from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Elsa Davidson, an assistant professor of anthropology at Montclair State University in New Jersey, said that her father contended with the effects of progressive spinal stenosis for several years but the painful condition “in no way diminished” his dedication to work.

Besides his daughter, Davidson is survived by two grandchildren.

MORE OBITUARIES:

Zeke Grader dies at 68; advocate for commercial fishing

Fred DeLuca dies at 67; co-founder of Subway sandwich chain

Norman Farberow dies at 97; psychologist was pioneer in suicide prevention

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.