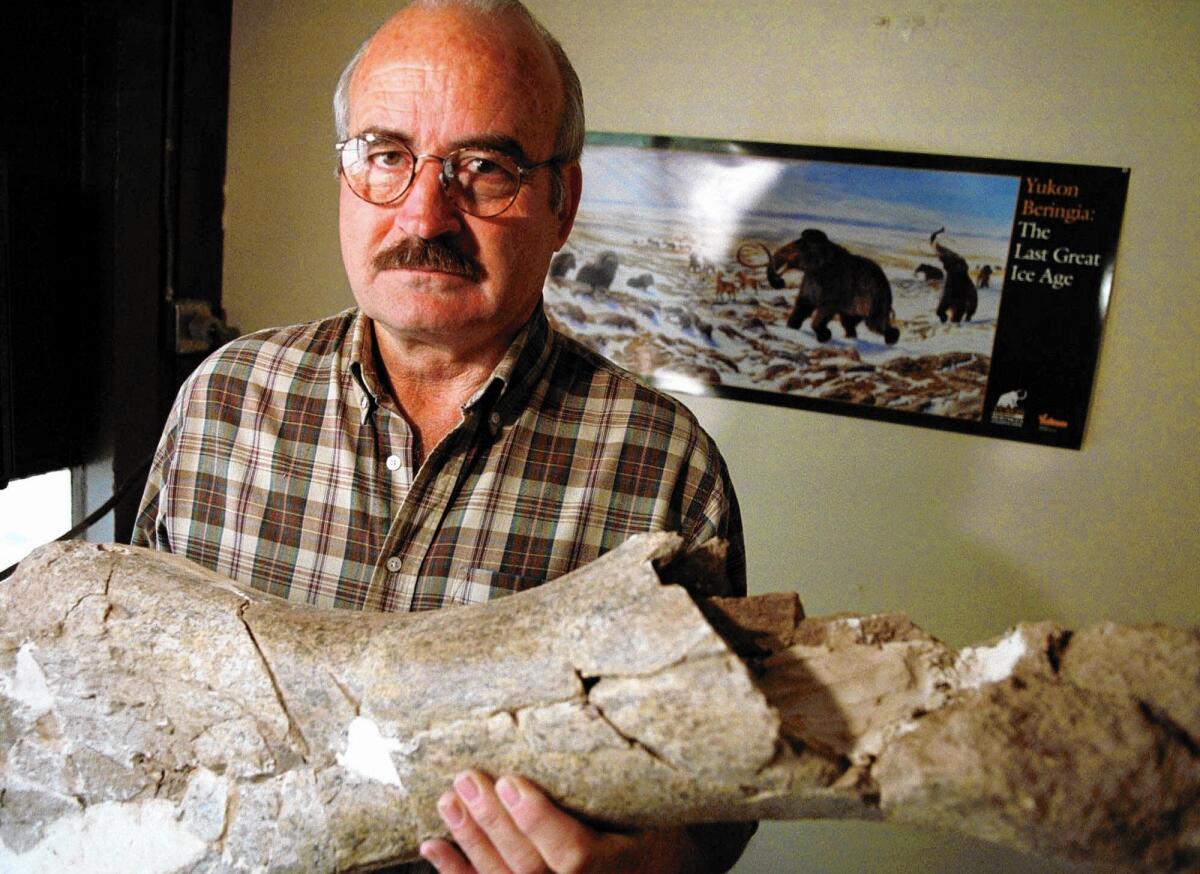

Larry Agenbroad dies at 81; paleontologist led Mammoth Site excavation

- Share via

On an archaeological dig in Arizona in the 1960s, something gnawed at paleontologist Larry Agenbroad every time human artifacts were uncovered. The excavation team went wild taking photographs and planning articles to burnish their credentials. But they ignored other remains clearly visible in the pit — the bones of giant mammoths who were killed there.

“He would say, ‘We just left them and walked away.’ It struck a chord with him,” said his son Brett. “He felt those remains were as important as anything human.”

Agenbroad’s compassion turned him into one of the world’s leading authorities on the giant beasts that disappeared thousands of years ago. Over the next four decades he took part in digs from Siberia to California’s Channel Islands and helped create the Mammoth Site, an unusual research center and museum in Hot Springs, S.D., where mammoth skeletons are displayed in the ground where the creatures died.

“The name Larry Agenbroad is really synonymous with Ice Age mammoths worldwide,” said Jim Mead, a paleontologist at East Tennessee State University, who called his longtime colleague “a great mammoth researcher.”

Agenbroad, who was chief scientist and director of the Mammoth Site, died Oct. 31 in Hot Springs from complications of kidney failure, his son said. He was 81.

The Mammoth Site evolved from a construction crew’s discovery of a mammoth tusk on a Hot Springs hilltop in 1974. The son of the contractor had been a student of Agenbroad’s at Chadron State College in Nebraska and alerted his former professor to the find.

Working with Mead and others, Agenbroad soon determined that the area was, as Mead recalled, “a mammoth site of mammoth proportions.” They estimated that it held the fossil remains of as many as 100 mammoths — believed to be the largest such concentration in the world. The remains of 61 have been recovered so far.

“It’s a spectacular site, virtually unique in the world,” said Daniel Fisher, a renowned mammoth researcher who directs the University of Michigan’s Museum of Paleontology. “Agenbroad’s work has done a great deal to interpret the circumstances leading to this unusual accumulation of fossil material. The site is so dramatic that it has acted as a catalyst and focal point for a great deal of scientific and popular interest in mammoths and the Ice Age.”

Agenbroad and his team found that most of the mammoths were males in their prime years. He theorized that while looking for food during an Ice Age winter they were drawn to the vegetation growing around a sinkhole, the sides of which were sharply sloped and covered with slippery shale.

To the adolescent males, the rewards outweighed the peril.

“They could sweep off three feet of snow and get last year’s grass, which is about as exciting as a bowl of cereal with no sugar, berries or milk,” Agenbroad told Smithsonian magazine in 2010. “Or they could go for the salad bar of plants still growing around the edge of the sinkhole.”

Weighing 14 tons each, with tusks 12 to 14 feet long, the bulky beasts slid into the sinkhole and never got out.

Agenbroad knew that their remains had to be left there.

“It’s more meaningful this way because the bones will never look more awesome than they do in the ground,” he told National Geographic in 1983.

One of six children, Agenbroad was born on a farm near Nampa, Idaho, on April 3, 1933.

He studied at Boise Junior College before heading to the University of Arizona, where he earned a master’s degree in 1962 and a doctorate in 1967 in geologic engineering. He spent most of his academic career at Chadron State College and Northern Arizona University.

Besides his son Brett, of Unalakleet, Alaska, Agenbroad is survived by his wife of 54 years, Wanda, of Hot Springs, son Finn of Denver, a brother, a sister and six grandchildren.

His explorations of a lost world took him to Santa Rosa Island, off the Ventura coast, where a nearly complete skeleton of a pygmy mammoth had been found in 1994. The following year, Agenbroad discovered the lower jawbone of a full-size mammoth nearby — tantalizing evidence, he said, that mammoths crossed the channel from the mainland during the Pleistocene Epoch and slowly shrank in the confines of the island.

In 1999 he traveled to Siberia as part of an international team of scientists invited to excavate the corpse of a woolly mammoth that had been locked in ice for more than 20,000 years.

It was an astonishing specimen.

“I usually only see bones and teeth, and in a couple of extraordinary finds, mammoth dung,” he said in a 2000 Washington Post interview. But this mammoth was intact — and still covered with long, coarse hair.

“It was,” he said, “my first opportunity to pet a mammoth.”

Twitter: @ewooLATimes

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.