Doomsday Clock moved closer to ‘midnight’ since Trump started talking about nuclear weapons

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — President Trump’s comments about the U.S. nuclear weapons arsenal have for months rattled arms-control advocates about how his administration might change half a century of policy and posture.

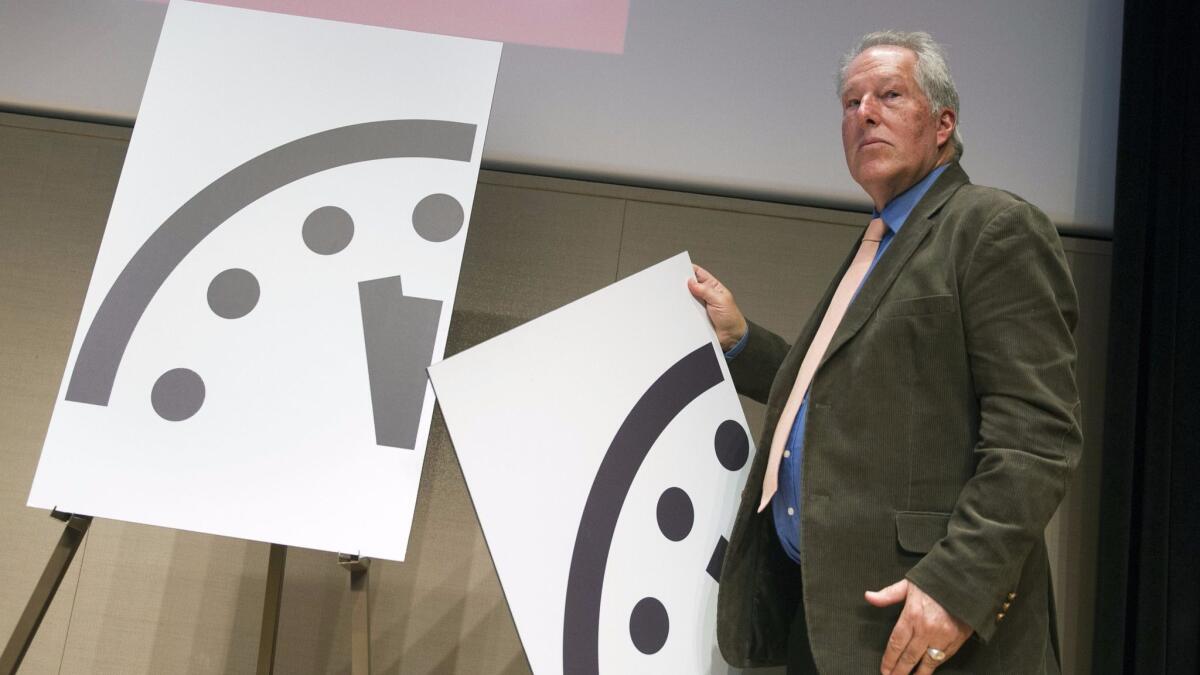

On Thursday, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists weighed in with its annual Doomsday Clock assessment. The metaphorical clock shows how close the world is to “midnight,” or a worldwide catastrophe.

The group, started by physicists who built the atomic bomb as part of the Manhattan Project, took the “unprecedented” step of moving the clock ahead by 30 seconds, to just 2½ minutes before midnight. It’s the closest the clock has been to midnight since 1953, when the U.S. and Soviet Union were in the early days of above-ground hydrogen bomb testing.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists said it made the decision based on the possible use of nuclear weapons, but includes climate change and technologies that could inflict irrevocable harm, whether by intention, miscalculation or accident in its calculation.

The clock held steady last year, after ticking down from 5 to 3 minutes to midnight in 2015, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and incursions into Ukraine.

“I lived through the tense and dangerous early to mid-1980s; it’s the reason I made understanding, controlling and eliminating nuclear weapons my career,” said Stephen Schwartz, a nuclear weapons policy expert and the organization’s former executive director. “I have no desire to go backward to that era.”

Trump’s comments first raised concerns among experienced arms control advocates when he repeatedly referred to nuclear weapons as “the nuclear,” which indicated an unfamiliarity with the subject. It was further heightened when he said he was amenable to more nations, namely Japan and perhaps Saudi Arabia, developing their own nuclear weapons, and that it was inevitable.

After winning the presidential election, he told MSNBC: “Let it be an arms race. We will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all.”

The same day he wrote on Twitter: “The United States must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability until such time as the world comes to its senses regarding nukes.”

Now Trump has taken over a government that is implementing an estimated $348-billion plan to modernize its nuclear forces. Begun under former President Obama, the effort has taken on increased significance amid the emergence of a defiant Russia and a new generation of nuclear powers, including India and Pakistan. It has also has raised questions of a renewed arms race like the one that defined much of the Cold War.

The administration is at work developing plans for fielding new land-based nuclear-tipped missiles that could be launched in minutes, underwater submarines capable to deliver a devastating atomic counterpunch to any surprise attack, and stealth bombers that could be scrambled for a long-range strike at a moment’s notice.

Over the last half a century, weapons treaties have led to a dramatic drop in the number of warheads. At the peak of the Cold War in the 1960s, the U.S. had more than 30,000 nuclear weapons — 400 targeted on Moscow alone.

The numbers fluctuate, but Russia currently has 428 more warheads than the U.S., while the United States has 173 more delivery systems, according to the State Department Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance. Under the New START Treaty, each country will deploy no more than 1,550 strategic weapons by February 2018.

However, the future of nonproliferation treaties appears bleak as Russia, North Korea, China, Pakistan and India all work to improve their nuclear arsenals and delivery systems.

The Pentagon is headlong into the decade-long process of developing a new stealth bomber, dubbed the B-21 Raider, and replacing the Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine. The Air Force last month started initial assessments of a new intercontinental ballistic missile.

The Energy Department has also embarked on an ambitious plan to extend the design life of existing thermonuclear warheads, improve national laboratories and facilities, and bring in the next generation of talented scientists.

The cost of all of this is estimated to approach $1 trillion over the next 30 years.

It’s a small price to pay, Defense Secretary James N. Mattis said during his confirmation hearing this month, because nuclear deterrence is the foundation of U.S. security.

“My view of the Department of Defense’s strategic priorities is that we must first maintain a safe and secure nuclear deterrent,” Mattis said. “I consider the deterrent to be critical because we don’t ever want those weapons used. So either the deterrent is safe and secure, it is compelling, or we actually open the door for something worse, whether it be a technical accident or political accident. So to me it’s an absolute priority.”

Twitter: @wjhenn

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.