Accused soldier’s family searches for answers

- Share via

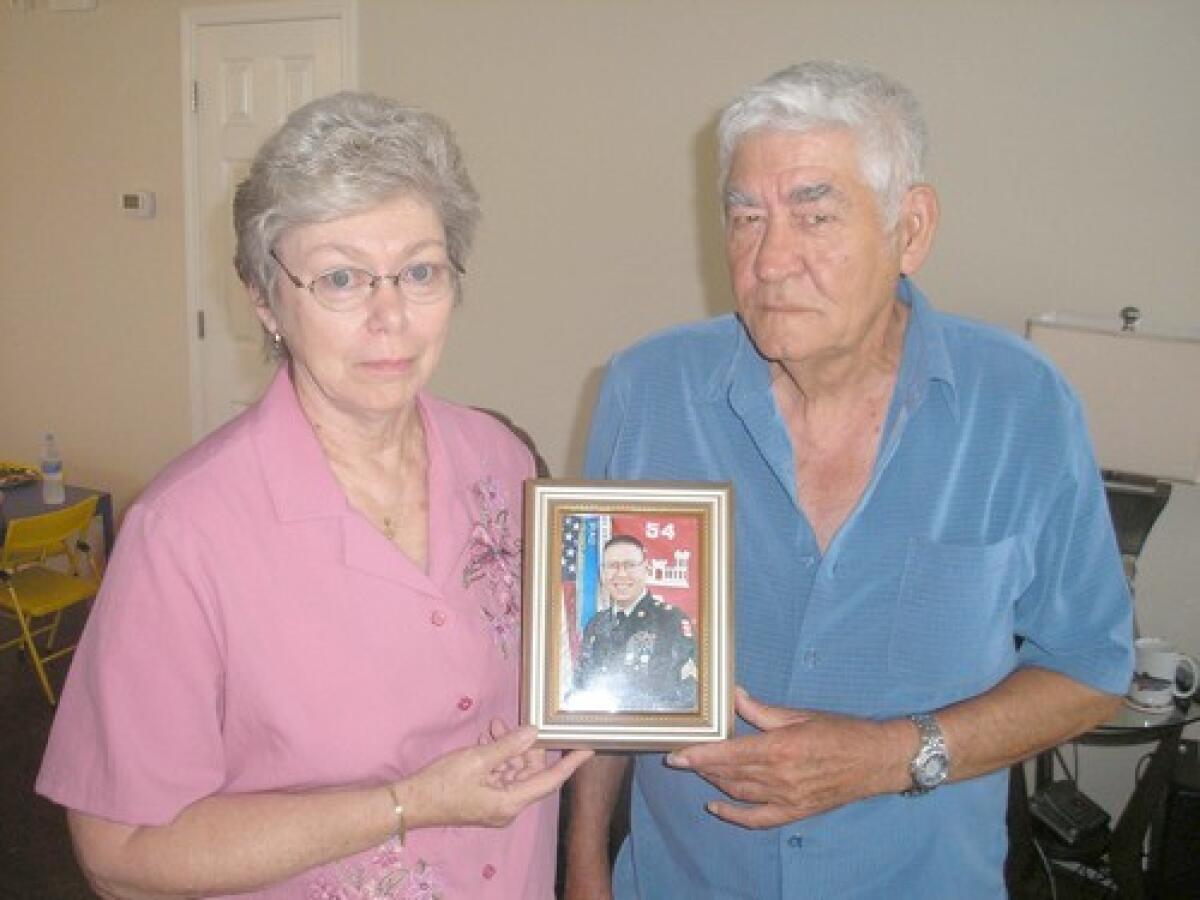

Reporting from Sherman, Texas — Tears come to Elizabeth Russell’s eyes when she thinks of the five Americans her son is accused of gunning down in a moment of rage in Iraq.

She prays for them at St. Patrick Catholic Church in nearby Denison: the Navy officer, the Army psychiatrist and the three Army enlisted men; their widows, their parents and their children.

She also prays for her son, Army Sgt. John Russell, who faces five counts of premeditated murder for what happened the morning of May 11 at a combat stress center on the outskirts of Baghdad.

Russell, 44, is in custody in Kuwait, awaiting an Article 32 hearing, the military equivalent of a preliminary hearing. Under military law, a conviction can carry a death sentence; the minimum is life in prison.

In more than seven years of war in Afghanistan and Iraq, there have been a handful of cases of alleged attacks between U.S. troops -- but never one in which a soldier stands accused of killing five colleagues.

The Russell case also brings up issues of how well the Army is evaluating the mental health of troops in the combat zones, many of whom, like Russell, have endured repeated deployments. The Army is now studying the psychological services available to soldiers in Iraq.

Elizabeth and Wilburn Russell live in the two-story house on Swan Ridge Drive in this tidy, middle-class community that was meant to be the dream home for their son and his German-born wife, Mandy, when he retired from the Army.

Russell had been a competent soldier -- a communications technician -- but hardly a stellar performer. Diagnosed as a boy with a learning disorder, he struggled through school, and in the military he found an economic stability that might have eluded him in civilian life.

After 16 years, he was still a sergeant. He had lost a stripe earlier in his career for unauthorized absence.

Russell planned, after retirement, to return to Texas and maybe to get a maintenance job at the Texas Instruments plant where his parents worked until their retirements.

The Russells, their three daughters, and John Russell’s 20-year-old son, John Michael II, are confused and obsessed about what they gingerly call “the event.”

“Every day, it’s all I think about,” said John Michael II, who inherited his father’s love of fishing and now works in a local bait shop. He had thought of joining the military but has changed his mind.

‘This wasn’t John’

All the Russells can think of is that Russell snapped under stress, a full year into his third combat tour in Iraq. His first tour had lasted 15 months, his second tour 12.

“This wasn’t John, not John,” Elizabeth Russell, 72, said quietly as she set the table for lunch.

E-mails and phone calls by Russell to family members suggested that he had been on a downward spiral emotionally for months.

After his second tour in Iraq, Russell had complained of sleeplessness and nightmares and sought help at the medical center at the U.S. base in Bamberg, Germany, where he was stationed. His wife said he saw a therapist three or four times and was given pills to help him sleep.

When his unit was set to redeploy to Iraq early last year, Russell got a delay because of a death in his wife’s family. In May 2008, he deployed to Iraq with a different unit. The new unit was not a good fit.

In February, Russell complained to his sister Lisa Russell Wilson, 48, about being ostracized and picked on. “He asked me to pray for him,” Wilson said. “He said: ‘I’m not going to make it. These people are after me.’ ”

On April 15, he e-mailed his mother: “I am not feeling good, I have something and I can’t get rid of it. Love John.”

Five days later, he described how he complained about mold in an air-conditioning system at his base.

“Hey mom, good I was not very nice on the phone to the people at the office, so I hope that they fixed it. I thank that the mold in my air con is making me sick, I turned it off and I feel better. Love John.”

To Mandy, his sister and mother, Russell made references to officers who singled him out for criticism and tough duty, like a three-day stint at a forward sentry post without relief.

At 6 feet 4 and in good physical shape, Russell could be an imposing presence, but the complaining and angry behavior were out of character, family members say. Wilburn Russell, 73, a blunt-talking former boxer and retired Department of Defense civilian employee, said that the changes in his son were alarming but that the family was helpless.

“Whether these things happened or not, they were real to John,” said his father.

On May 6, John Russell sent an e-mail to his wife:

“Hey, baby, for the last two days I have been in hell. I was threatened buy a soldier. I didn’t know what to do. All it is all said and done, I am left feeling so terrible you could just never know. These people are not good people and I think that I am going a little crazy.

“I really need to get out of the Army soon. I came close to losing everything that I have worked for.”

A day later, Russell e-mailed Mandy again: “I went off on an officer, but he is not going to get me in trouble because he was one of the people that threatened me. So we have a clean slate. Love John.”

Near going home

What happened in the next few days is unclear.

Whether voluntarily or under orders, Russell went to the combat stress center at Camp Liberty where psychiatrists and other mental health workers evaluate soldiers for signs of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

Russell was within weeks of the end of his yearlong deployment -- which is often an unsettling time for service personnel. As troops prepare to return home, feelings of inadequacy or failure can overwhelm them as they ponder explaining their deployment to family members or other troops.

At the stress center, Russell was given medication -- his family is unclear what type -- and officials took away his sidearm, a routine precaution for soldiers receiving counseling.

On May 11, Russell had some sort of dispute at the center and was ordered to leave. Once outside, he allegedly grabbed a gun from his escort, burst into the center and started firing. He meekly submitted to arrest minutes later.

Dead were Navy Cmdr. Charles Springle, 52, of Wilmington, N.C.; Maj. Matthew Philip Houseal, 54, of Amarillo, Texas; Staff Sgt. Christian Enrique Bueno-Galdos, 25, of Paterson, N.J.; Spc. Jacob David Barton, 20, of Lenox, Mo.; and Pfc. Michael Edward Yates Jr., 19, of Federalsburg, Md.

Russell’s family members are reluctant to use the word “victim,” not wanting to be insensitive to the agonized relatives of the five dead. Still, they feel that John was also a victim of what happened May 11 -- a victim of unrelenting stress from deployments to Iraq totaling 39 months and an Army mental health system that failed him.

“I don’t think he was in his right mind,” Mandy said in a telephone interview.

The Army is also interested in the state of Russell’s mind. He was brought to Walter Reed Medical Center in Washington for psychological tests in June before being returned to Kuwait. His family was not allowed to see him.

Looking back now, it is possible to see many frustrations in Russell’s life. At age 8 he was diagnosed with the reading disorder dyslexia. When he was 12, the family moved from Plano, Texas, to Sherman, where the school system put Russell in a special-education class.

“John was upset because he thought he was considered a dummy,” his mother has written in a family history. He tried playing football but leg problems forced him to quit.

He quit high school and got a job in a restaurant. There he met a young woman who encouraged him to return to school and get a diploma in 1985. The two married that year and had a son in 1989.

The marriage soured. “John went thru a depression because he was out of work and they were divorced in 1993,” his mother wrote.

He had joined the Texas Army National Guard after high school. In 1995, after working a series of maintenance jobs, he joined the regular Army and deployed for a year to Korea. He also served six months each in Bosnia and Kosovo.

Russell and Mandy met in Germany in 1997 and married in 1999. The couple have no children together. Mandy, 33, has visited Texas and shared her husband’s dreams about retiring there.

In 2009, he still needed another four-year hitch to qualify for a full pension. His family believes that a threat from an officer to block his reenlistment -- real, false, or imagined -- may have pushed him into violence.

When the news broke about the shootings at Camp Liberty, reporters raced the 60 miles north from Dallas to find the Russells at their son’s home in Sherman. His father told the reporters: “I hate what that boy did.”

Words of support

When the press left, neighbors came by to express condolences. Some offered to cook, others to do chores -- in the manner of neighbors helping a family that has suffered a death.

Within days, the Russells began getting letters, some hate-filled but most from women offering support.

One woman wrote: “Hopefully, if anything good can come of this, John’s hell will help to bring real change in the Army system.”

Another woman who said she has two foster sons in the military sent this message: “I’m sorry that the military he loved didn’t take better care of him. My family and I will be praying for you and your family.”

Austin-based lawyer James Culp, a former Army infantry sergeant, has counseled the Russell family to be realistic. He has represented five troops accused of murder or manslaughter in Iraq or after their service.

Culp said that although there seems little doubt that Russell’s mental state was diminished by his three tours in Iraq, “the hurdle to prove insanity in a criminal trial is very difficult.” Proving that the shooting was “in the heat of passion” will also be difficult, he said.

“Any result in this case that spares Sgt. Russell’s life will be a victory of sorts,” Culp said.

These days, Elizabeth Russell peppers her son’s military lawyer with questions but gets few answers. She gathered up books to send to her son in Kuwait: Western novels by Louis L’Amour, Roman history and suspense potboilers by Dean Koontz.

While in the brig, he had a “hostile meeting” with a psychiatrist and fired his first lawyer. His mother remembers a brief telephone call with him four days after “the event.”

“He didn’t remember anything about that day,” she said. “He sounded really tired, exhausted.

“I told him we loved him.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.