After Ferguson, white public officials soften their response

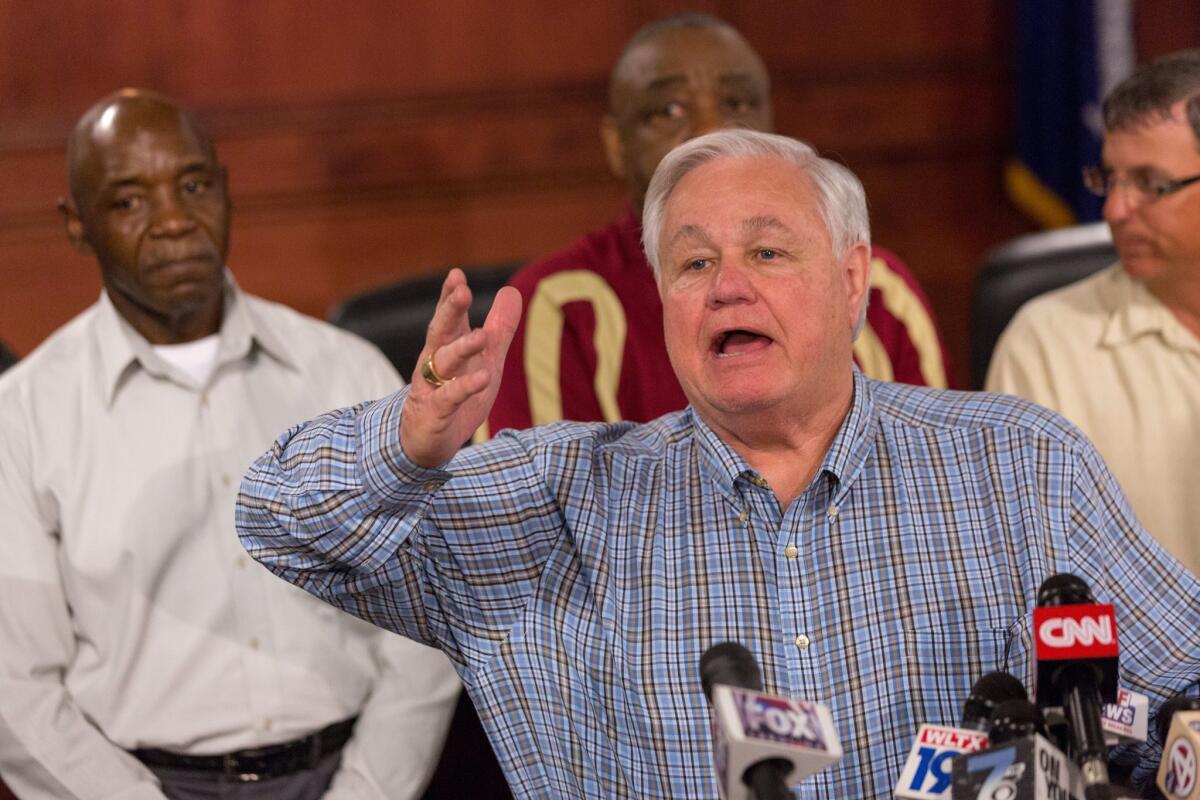

North Charleston, S.C., Mayor Keith Summey answers questions during a news conference after an officer fatally shot Walter L. Scott.

- Share via

The response was nothing like what happened in Ferguson, Mo.

Days after Walter L. Scott was shot to death as he ran away from a South Carolina police officer, North Charleston’s white mayor and white police chief paid condolences to his grieving family.

They promised a police escort for Scott’s funeral and publicly condemned the killing by Officer Michael T. Slager, who has been charged with murder.

“This has been a horrible tragedy in our community,” North Charleston Mayor Keith Summey told reporters. “Please pray for this family.”

Nationwide, after Missouri officials’ stumbling response to the Aug. 9 Ferguson police shooting of unarmed black 18-year-old Michael Brown, the tone and approach of white public officials is shifting.

“Things have changed considerably,” said John Gaskin III, a black St. Louis community activist. “Quite honestly, Ferguson was the Watergate of public relations. It was a disaster … I think a lot of people, many, learned from Ferguson.”

Officials in Ferguson and St. Louis County were slow to release information after Brown’s shooting and responded to protests with an intimidating police presence.

The Ferguson police chief — Thomas Jackson, who has since resigned — took almost a week to reveal the name of the officer who killed Brown, and when he did, also implicated the dead man in a strong-arm robbery. That juxtaposition angered demonstrators and fueled more unrest, which simmered for months.

Since then, officials across the country have aggressively moved to get official information out quickly and eliminate any hint of racism.

“Ferguson was a wakeup call, really, for police departments worldwide,” said John Guilfoil of Georgetown, Mass., who runs a public-relations company that serves about 50 police and fire departments and town governments.

When a white Madison, Wis., police officer fatally shot biracial 19-year-old Tony Robinson after a struggle, Madison Police Chief Michael C. Koval, who is white, quickly appeared on television to provide facts of the case and express his understanding of protesters’ grievances.

Although tempers flared in Madison over Robinson’s March 6 death, protests remained peaceful.

“When a young person is killed, in this case at the hands of the police, and he’s only 19, and it turns out he’s unarmed, the appropriate thing first of all is to mourn the loss of life, to say you’re sorry about the loss of life, and be transparent about what you know so it doesn’t look like there’s a clandestine cover-up,” Koval said in an interview this week.

Koval also sought to avoid appearing to smear the dead man in the media, he said.

“I must have been asked 60 times if I was asked once, ‘tell us about [Tony Robinson’s criminal] record, tell us about the reports of his drug record,’” Koval said.

He refused. “It is not the role of the police to defame or bring disrepect on a young person whose life ended all too quickly,” he said.

When the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity at the University of Oklahoma was caught on video singing an anti-black chant that alluded to lynching, the university’s president immediately banned the fraternity, expelled the chant’s leaders and spoke out at a rally organized by a black campus activist group.

Showing decisiveness and sympathy after racially tense incidents is not without institutional risk.

After a grand jury did not indict a police officer in the death of Eric Garner late last year, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio expressed empathy for young black men who encounter police, saying he had warned his biracial son about how to behave around police.

When a suicidal gunman assassinated two NYPD officers soon after, a police union official accused the mayor of having blood on his hands, and officers protested publicly.

University of Oklahoma President David L. Boren’s decision to ban the SAE fraternity from campus may have exposed the university to a potential lawsuit. The fraternity has hired a prominent defense attorney, and legal experts say the frat’s racist chant may be protected by the 1st Amendment.

The swift official response in North Charleston this week has received a generally favorable reception from black activists, largely due to the murder charge against the officer.

At a Wednesday news conference, the mayor and police chief still confronted a room of protesters chanting: “No justice, no peace! No justice, no peace! No justice, no peace!”

Mayor Summey told the crowd: “We understand how you feel and what you’re saying.… We don’t have any issues with that.”

The protesters challenged officials for a while, but when the news conference was over, after night fell, quiet reigned on the streets of North Charleston.

Follow @MattDPearce for national news

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.