Bipartisan praise for an end to tough federal sentencing

- Share via

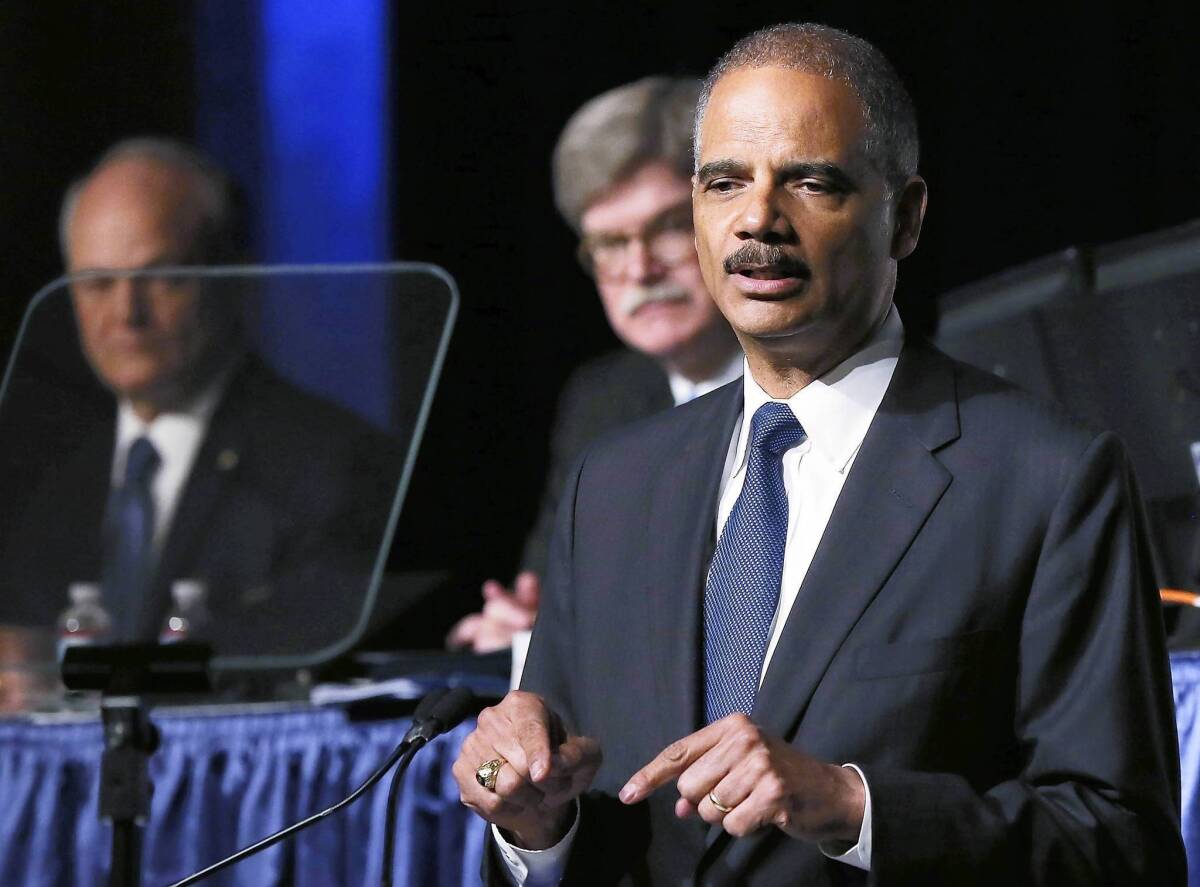

WASHINGTON — In a sign of growing disenchantment with the war on drugs, conservatives joined Democrats and reform advocates Monday in praising Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr.’s declaration that it was time to rethink get-tough policies that have tied the hands of judges and swollen the populations of federal prisons.

The nation’s top law enforcement officer, decrying the “moral and human costs” of mass incarceration, said he would instruct federal prosecutors to change the way they charge some drug offenders to avoid triggering “mandatory minimum” sentencing laws.

The federal prison population has exploded even as populations in state prisons have declined steadily.

“The course we are on is far from sustainable,” Holder said, speaking to the American Bar Assn. in San Francisco. “As the so-called war on drugs enters its fifth decade, we need to ask whether it, and the approaches that comprise it, have been truly effective.”

Holder also said the department would increase efforts to find alternatives to incarceration and to smooth the compassionate release of severely ill prisoners who were no longer a threat to the public.

Some former prosecutors said the changes probably wouldn’t affect huge numbers of cases. But advocates for drug policy change said Holder’s statements were long overdue and could reframe the debate about sentencing policy.

“It’s the first time a U.S. attorney general has spoken so forcefully or offered such a detailed proposal for sentencing reform — and particularly notable that he framed the issue in moral terms,” said Ethan Nadelmann, executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance.

Holder is essentially following the lead of states, including Georgia, Texas and Ohio, that have reformed sentencing rules, given judges more discretion and steered some offenders into treatment. State prison populations have dropped since 2009, according to Justice Department statistics.

Not so in the federal system. There are about 218,950 inmates, an 800% increase since 1980. Nearly 47% are drug offenders, and prison costs account for about a third of the Justice Department’s budget.

Those spiraling costs have helped convince conservatives to embrace sentencing reform. In March, Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) joined with Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick J. Leahy (D-Vt.) to introduce legislation to expand judges’ discretion in federal criminal cases. Sens. Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) have introduced another bill that would ease mandatory sentencing rules.

“I am encouraged that the president and attorney general agree with me that mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent offenders promote injustice and do not serve public safety,” Paul said in a statement.

The mandatory sentencing policies once had broad support in Congress. After the cocaine overdose death of basketball star Len Bias in 1986, Democrats and Republicans rushed to outdo each other to support a law that tied the hands of judges and forced harsh mandatory sentences on drug dealers.

Many federal judges have chafed at the restrictions. In an opinion last year, U.S. District Judge John Gleeson said he was forced to impose a five-year sentence on a street-level dealer. “It was not a just sentence,” he wrote, calling on Holder to change the charging guidelines to target drug kingpins, as Congress intended.

“It has been that way for a generation — get tough as though it works, but it hasn’t worked,” said Craig DeRoche, a former Republican speaker in the Michigan House and president of Justice Fellowship, a conservative group that advocates sentencing reform. He said conservative governors had led the way toward better approaches.

There were some voices of opposition. House Judiciary Committee Chairman Robert W. Goodlatte (R-Va.) said overhauling sentencing rules was a good idea, but Holder should be working with Congress rather than “selectively enforcing our laws” and overstepping executive power.

Holder’s policy change instructs U.S. attorneys how to write up certain kinds of drug cases involving low-level offenders without a weapon. In those cases, Holder told prosecutors not to include the amount of drugs on charging documents, if the amount would trigger the mandatory guidelines.

Some advocates say prosecutors slap defendants with the severest possible charges to convince them to cooperate with law enforcement. “I think prosecutors have become addicted to it in the past two decades,” said Julie Stewart, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, adding that prosecutors have other tough tools at their disposal besides the threat of mandatory sentences.

Holder’s new policy will affect only defendants without a “significant criminal history,” said Matt Kaiser, a Washington-based criminal defense attorney and former federal public defender. “It’s not that the change helps nobody, but it’s so close to nobody that the practical effect is negligible.”

Christi Parsons in the Washington bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.