Hasan’s Ft. Hood sentencing: Widow relives the hours of not knowing

- Share via

FT. HOOD, Texas – Like so many other Army wives, when Angela Rivera heard there had been a shooting at this central Texas post four years ago, the first thing she did was call her husband’s cell phone.

And like so many others, there was no answer.

On Monday, testifying at the sentencing of the man convicted of murder in the mass shooting, Rivera relived the uncertain hours of Nov. 5, 2009.

There were 13 dead and more than 30 wounded that afternoon. But no names had been released. Rivera had no way of knowing if they included her husband, Maj. L. Eduardo Caraveo.

She watched the news at her home in Woodbridge, Va., hoping for clues. It was no help.

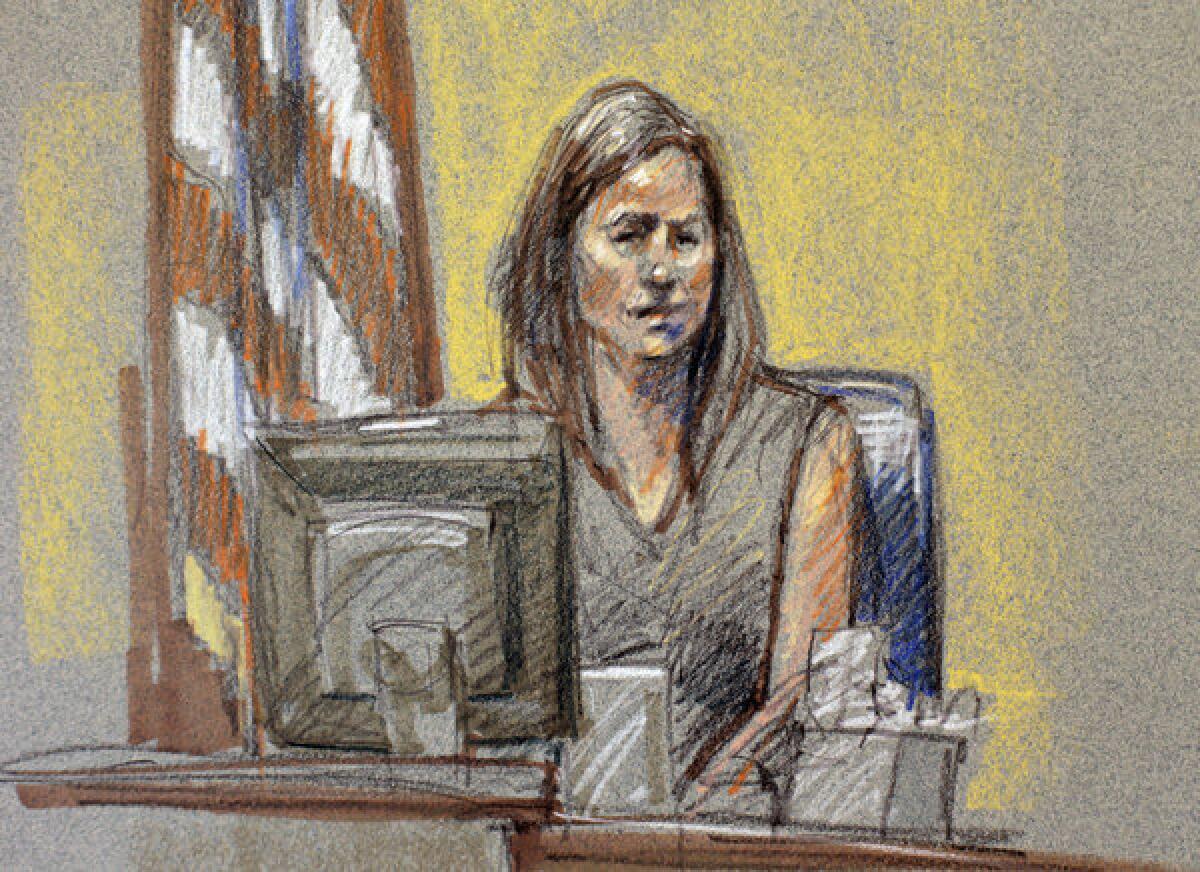

“They just kept repeating the same thing: 13 dead,” Rivera said Monday as she sat on the stand, her long brown hair loose around the shoulders of her fitted black dress as she faced the man responsible.

As Rivera recounted the events that followed, how she slowly watched the life she had built unravel, her brown eyes filled with tears.

U.S. Army Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan stared back, impassive.

The Army psychiatrist, who is defending himself, was convicted Friday on 13 charges of premeditated murder and 32 charges of attempted premeditated murder and now faces a possible death sentence. The same jury that convicted him is handling his sentencing, a group of 13 officers, all Hasan’s rank or higher.

Jurors watched Monday as Rivera described her husband and smiled at times at the memories. Caraveo, 52, was a psychologist with a private practice who had worked with inmates at prisons in Arizona, California and Washington D.C. while serving in the National Guard for a decade.

He had met Rivera at a party in Tucson in 2002, drawn by her smile. Each had children — two girls and two boys. Six months after they met, they married and later had a son of their own, John Paul.

In November 2009, Caraveo was at Ft. Hood preparing for his first deployment with a combat stress unit to Afghanistan. The night before the shooting, his children had gathered for a video-chat with him.

That was the last time they talked.

The following afternoon, as news of the shooting spread, Rivera called everyone she could think of near Ft. Hood: the Red Cross, local hospitals, Army officials.

All the while she kept checking for a missed call from her husband. They had an arrangement. They never left messages. If they saw a missed call from one another, they just called back.

Hours later, she was still waiting.

At 10:45 p.m., Rivera phoned her sister.

“They’re going to come and knock on my door and tell me he’s dead,” she said, begging her sister to come watch the kids so that she could fly to Ft. Hood to find her husband.

Instead, Rivera kept calling, seeking news. An official at Ft. Hood told her that they had notified all the families of the dead. She went to sleep, still uneasy.

At 5:25 a.m., the doorbell sounded.

As Rivera approached the door, she could see them through the glass: two Army uniforms.

“All I could say was I knew it. I knew he was dead because he did not call me back and he always did,” she said on the stand as a relative in the front row of the gallery dabbed her eyes.

Rivera thought of her husband’s family. He was the youngest of seven. They would be crushed.

She thought of their youngest son, John Paul, who was 2 years old.

As she drove the boy to the airport to pick up relatives in mourning, he kept asking the same question: Were they going to get Daddy?

Caraveo had been scheduled to fly home for Thanksgiving.

Instead, his wife received his Army backpack containing his camera and a few final photos snapped by his battle buddy. There was Maj. Caraveo, in fatigues and helmet, hoisting a gun and smiling broadly under the mustache he coveted. Prosecutors entered the photo into evidence Monday and displayed it on a small screen for the jury and Hasan, who didn’t react.

Rivera testified that she has had to leave the home she shared with Caraveo. She couldn’t cope with all the reminders: his car in the garage, his empty chair.

But she saved his cell phone. As long as she kept it activated and charged, she and other relatives could call and hear him on the voice mail, summoning his voice from the past. It was a small comfort, a legacy for their youngest son.

Then one day Rivera called and made a startling discovery. Maj. Caraveo’s voice had disappeared. She called the cell phone company, where a worker told her the voice mail system had changed. There was nothing she could do. Her husband was gone.

ALSO:

Obama awards Medal of Honor to Afghan war veteran

Delbert Belton’s death: 2 Spokane teens to be tried as adults

Delbert Belton’s daughter-in-law: ‘They need to pay the consequences’

Follow L.A. Times National on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.