States try to tackle ‘secret money’ in politics

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Early last month, state lawyers and election officials around the country dialed into a conference call to talk about how to deal with the flood of secret money that played an unprecedented role in the 2012 election.

The discussion, which included officials from California, New York, Alaska and Maine, was a first step toward a collaborative effort to force tax-exempt advocacy organizations and trade associations out of the shadows.

The unusual initiative was driven by the lack of progress at the federal level in pushing those groups to disclose their contributors if they engage in campaigns, as candidates and political action committees are required to do.

“There is no question that one of the reasons to have states working together is because the federal government, in numerous arenas, has failed to take action,” said Ann Ravel, chairwoman of California’s Fair Political Practices Commission, who organized the call with officials from about 10 states.

The 2012 campaign set a high-water mark for independent groups, which unleashed more than $1 billion into federal races, three times as much as in 2008, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics.

The bulk of that spending was by “super PACs,” which must disclose their donors. But nonprofit advocacy groups and trade organizations, which do not have to reveal their financial backers, accounted for $309 million. Among them were the conservative Crossroads GPS, the liberal Patriot Majority USA and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The actual influence of such organizations was far greater, as tax-exempt groups also poured tens of millions of dollars into election-related activity that they were not required to report.

Advocates for disclosure say it is essential for the public to know who is trying to influence elections. But opponents say making donors public would infringe on their privacy and could intimidate some from participating in politics.

For now, state officials who participated in the conference call are sharing information on their campaign finance regulations and experiences with advocacy groups in their states. But the agencies may move to team up on investigations and work together to pressure federal agencies to do more.

The push by state regulators comes as scrutiny of nonprofit groups is gaining new attention at the federal level. On Capitol Hill, Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.) plans to use his influential post as head of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations to press for greater oversight of these groups. And the Securities and Exchange Commission is considering a rule to require publicly traded corporations to reveal their political donations.

But disclosure advocates acknowledge they face a steep climb in Washington.

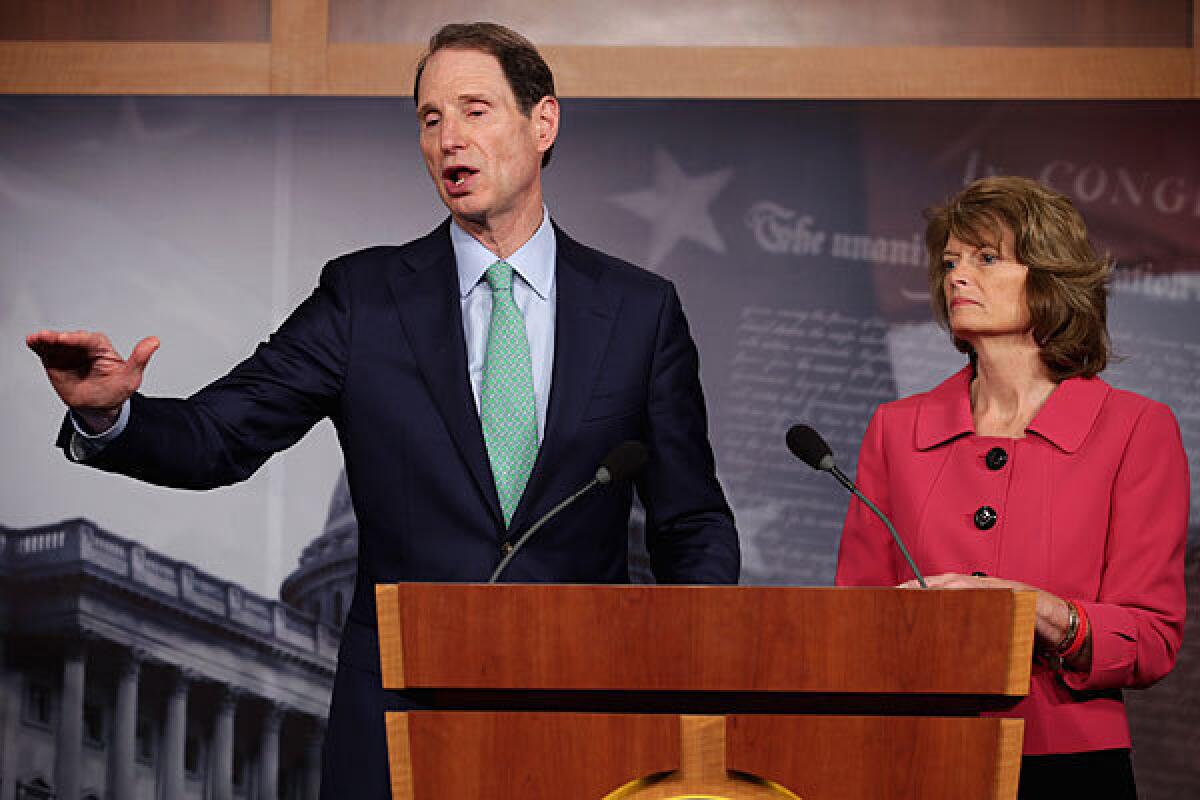

“I have no reason to believe this is going to be easy,” said Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), who unveiled a bipartisan disclosure bill with Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) last month. She is the first GOP senator to sponsor such a measure in recent years; it is not clear whether other Republicans will come aboard.

“Unless both sides realize that disclosure is important to all of us, it’s not going to happen,” Murkowski said.

Much of the focus is on “social welfare” organizations set up under section 501(c)4 of the tax code, which can engage in elections as long as politics is not their primary purpose. Such organizations have proliferated since 2010, when the Supreme Court ruled in the Citizens United case that corporations could spend unlimited sums on elections. The decision also applied to many nonprofit groups.

State officials criticize multiple federal entities as failing to respond swiftly to the new environment. The Internal Revenue Service has asked some nonprofits for more information about their activities, but has not indicated whether it has launched any formal investigations. And measures to compel disclosure have stalled in Congress and at the Federal Election Commission.

In California, the Fair Political Practices Commission recently issued a series of subpoenas as part of an investigation to uncover the source of $11million involved in two ballot measures last fall.

The money passed from Americans for Job Security, a Virginia nonprofit, to the Center to Protect Patient Rights in Arizona, to another Arizona nonprofit called Americans for Responsible Leadership, and then to the conservative Small Business Action Committee in California.

The committee was working against Gov. Jerry Brown’s tax increase measure and in support of another measure intended to curb the ability of unions to raise money for political activity. The source of the money remains unknown.

Lawmakers in more than a dozen states have proposed legislation to force such groups to disclose their donors. Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley signed a measure Thursday requiring independent groups that make election-related donations or expenditures of $6,000 or more in a four-year election cycle to disclose information about their top donors. It will take full effect in 2015.

An even more expansive effort is underway in New York, where Atty. Gen. Eric Schneiderman plans to issue regulations by June to require nonprofit groups that spend $10,000 or more on state and local elections to detail their political expenditures and disclose donors who give $1,000 or more.

“As long as Washington refuses to act, New York will serve as a model in shining light on this dark corner of our political system and protecting the integrity of nonprofits and our democracy,” Schneiderman said in a statement to the Los Angeles Times.

Advocates on both sides expect the state measures will trigger litigation. In the meantime, the moves are causing anxiety among tax-exempt groups and their donors.

“There’s deep concern,” said Larry Norton, a campaign finance lawyer in Washington who represents many nonprofits and trade groups. “It probably has a chilling effect on organizations themselves, and I think will likely have an impact on their fundraising.”

Opponents of new disclosure requirements say the measures are driven by Democrats who want to rein in conservative voices. O’Malley and Schneiderman are both Democrats.

“Perhaps some people don’t like what we’re doing, so they’re trying to change the law,” said Tim Phillips, president of Americans for Prosperity, a group backed by the industrial billionaires Charles and David Koch. The organization spent more than $190 million in the two-year 2012 cycle, according to Phillips, but was required to report only a fraction of that sum.

With so much money at stake, many of the efforts are running into strong political head winds.

In Montana — where a 2012 U.S. Senate race attracted a record $48million in spending, more than half from outside groups — a bipartisan effort to force greater disclosure died last month in the waning days of the legislative session. Republicans quashed it, fearing it would put their party at a financial disadvantage.

“They all say they don’t like dark money,” said Montana state Sen. Jim Peterson, a Republican who crossed many in his party to sell the measure — his farewell after 12 years in the Legislature. “But when push comes to shove, there are elements on both sides of the aisle that are afraid to let it go.”

Gold reported from Washington, Megerian from Sacramento and Barabak from Helena, Mont.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.