Protest to nowhere

- Share via

Poetry, as Auden famously instructed us, changes nothing -- and neither, despite all the predicted turmoil in San Francisco today, do the Olympics.

Still, the city’s entire police force and half the rest of the cops in the Bay Area, along with the Highway Patrol and the FBI, will be out today, attempting to protect the Olympic torch as it makes its ceremonial passage along the Embarcadero on its way to Beijing and this summer’s Games.

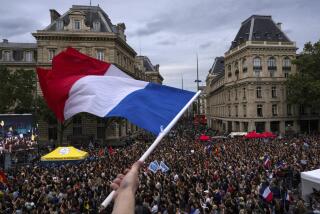

Thousands of protesters opposed to Chinese oppression in Tibet already have attempted to block the ceremonial run through London and Paris. In San Francisco, pro-Tibet activists are likely to be joined by others who believe that China’s close relationship with Sudan encourages Khartoum’s murderous policies in Darfur.

Tibet and Darfur are particularly popular causes in Hollywood, and California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger endorsed the protests Monday. (West of La Cienega, the Dalai Lama has higher approval ratings than Tom Hanks.) Sen. Hillary Clinton called on President Bush to boycott the opening ceremonies in Beijing. Many protesters are urging athletes to do the same; some are urging a blanket boycott not just of the opening but of the Games themselves.

Chinese conduct in Tibet and Sudan is reprehensible, so all this drama is cathartic in the way protests tend to be. But whether it will have much effect on China’s behavior is another question altogether. If history is any guide, the answer is no.

Essentially, the arguments over Olympic protests -- of which boycotts are the most extreme -- break down into two camps. One (call them the pragmatists) holds that the value of “engaging” oppressive regimes far outweighs the benefits of isolating them and that, over time, close contact with democratic societies in as many areas as possible will persuade the oppressors to change their ways. Another group (the one to which the protesters belong) argues that contact is complicity. Human rights violators, they argue, need to be forcefully confronted in every available forum.

When it comes to the Olympics, the fact of the matter is that both approaches have been tried in the past -- with precisely the same negligible results. In 1936, serious movements urging an outright boycott of the Berlin Games were mounted in the United States, Britain, France, Sweden, Czechoslovakia and the Netherlands. Adolf Hitler had come to power two years after the International Olympic Committee had awarded Berlin the Games as a symbol of Germany’s emergence from its post-World War I isolation.

By the time the opening ceremonies began, Nazi repression was in full swing, extending into areas directly involving the Olympics. In 1933, for example, all Jews were expelled from the German sports federations. In the weeks before the Games began, all the Gypsies near Berlin were confined in concentration camps. The Nazis, moreover, were quite forthright about their intention to use the Games to showcase their new “Aryan” society.

Even so, the anti-boycott forces prevailed, arguing that the best way to show the Germans their errors was to go to Berlin and compete against them. Nine Jewish athletes did win medals in Berlin, including five Hungarians and one token Jew on the German team, Helene Mayer, who had been removed from the Offenbach fencing club but ultimately was allowed to participate. There were seven Jews and 18 African Americans on the U.S. team; one was track star Jesse Owens, whose four medals made a mockery -- according to the anti-boycott faction -- of the Nazis’ racial pretensions.

Owens’ brilliance notwithstanding, the Berlin Games did nothing to alter German intentions or behavior and provided Hitler with a major propaganda victory. So much for the engagement-is-destiny argument.

What about the biggest boycott in Olympic history? Did that have more of an effect? The United States and 64 other countries, acting at President Carter’s behest, refused to attend the 1980 Moscow Games as a protest against the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan the year before. That’s about as effective a protest and boycott as you’re going to get. The result? The war in Afghanistan dragged on until the Soviets were forced to withdraw in 1989.

Protests or boycotts won’t get the Chinese out of Tibet or disengaged from Sudan. In fact, if the Beijing regime -- which has staked a lot on this Olympiad as a kind of international coming-out party -- is sufficiently embarrassed, repression in Tibet may worsen because the Chinese reflexively blame that region’s exiles for agitating and misleading the West.

That doesn’t mean that Tibet and Darfur shouldn’t be raised with Beijing whenever possible; it just means that the road to human rights in both places will -- as in China itself -- entail a long march rather than a quick fix.

--

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.