Three Americans, one plane: Seeking closure for a WWII disappearance

Located adjacent to to Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, the Leatherneck Museum was keenly interested in the SBD-1. After the Navy rejected that variation because of range limitations, it gave the planes to the Marines.

- Share via

Herbert McMinn grew up on a farm in the middle of Texas, in a tiny town called Gouldbusk, population 150. He planned to go back when the war was over, raise livestock and plant his feet and his future firmly on the land.

First he had some work to do in the sky.

It was Nov. 21, 1942, a Saturday, two weeks shy of a year after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that ushered the United States into World War II. McMinn — 24, unmarried, one of four children — was a Navy pilot, trained in Corpus Christi and then San Diego. Now he was in Illinois, practicing takeoffs and landings on a makeshift aircraft carrier steaming around Lake Michigan.

He flew an SBD Dauntless dive bomber. Although pilots joked that SBD stood for Slow But Deadly, the plane already had proved its worth at the Battle of Midway, where squadrons of them darted down to sink four Japanese aircraft carriers, changing the tide of the war in the Pacific theater. Dive bombers were rock stars.

Sometime in the afternoon, people noticed Ensign McMinn missing. He’d never made it back from carrier practice to Glenview Naval Air Station. When a civilian standing on the lakeshore in Chicago reported he’d seen a plane go into the water about five miles out, officials put two and two together.

For 12 days they dragged the lake. No plane, no body, no matter. The Navy declared McMinn dead, one of about 15,000 aviators killed during training in the war.

To his family, though, it remained an open sore. His parents, Floyd and Jewell McMinn, pleaded with the Navy to find him or his plane or at least the college ring from Texas A&M that he always wore.

“No one but God knows what we have suffered,” they wrote in a letter to the secretary of the Navy dated Jan. 13, 1946, more than three years after the disappearance. “If he could have been found, it would have been much easier for us.”

They put a marker in the ground at Rockwood Cemetery, but without any remains to place in the grave, it was hard for them to pay their respects. To honor the sacrifice he had made for his country. To remember.

“It was incredibly frustrating to the entire family,” said Bryan Lynch, the missing airman’s great-nephew. “By the time I came around, in 1961, nobody was talking about it much any more. It was just a thing that had happened.”

Years went by, then decades, and McMinn’s parents died without the closure they so desperately wanted. So did his siblings. Passed down to their survivors were a few reminders of what had been: Photos of Herbert, a few letters, his violin.

But if the family thought nobody else cared, they were mistaken. They didn’t know yet about Taras Lyssenko, co-founder of a company that pulls old warbirds from the depths of Lake Michigan. They didn’t know about Bob Cramsie, a longtime aviation mechanic in San Diego who has volunteered thousands of hours in the past four years at the Flying Leatherneck Museum, helping to restore historic airplanes.

One in particular.

‘A story of us’

Lyssenko, 56, is a brash, assertive descendant of Ukranian Cossacks, known for their independent streak. A Michigan businessman who promotes emerging defense and energy technologies, Lyssenko likes to do things his way, and sometimes he ruffles feathers. People use words like “interesting” and “a real character” to describe him.

He grew up near Chicago hearing stories about ships that had gone down in the Great Lakes. As teens, he and a friend went out in a rickety boat, looking for wrecks. “It’s a wonder we weren’t killed out there,” he said.

When scuba divers created a media-stir by discovering a World War II-era TBM Avenger on the bottom of Lake Michigan, Lyssenko and his partner changed their focus. Soon they found a plane under the water, too, a Wildcat fighter.

That was in 1977, and they moved on to other things: college, military service. In 1986 they began hunting for planes in earnest, eventually using side-scan sonar and other equipment. They learned that dozens of planes had crashed in the lake during the war as 63,000 pilots trained nearby, many of them taking off and landing on the USS Wolverine and the USS Sable, paddle-wheel luxury ships that had been converted into aircraft carriers.

Lyssenko’s company, A and T Recovery, pulled up several planes and sold them to museums interested in restoring them. That drew the attention of the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Fla., which was trying to build its own collection.

“Lake Michigan really opened a whole new chapter of Naval aviation history on display,” said Hill Goodspeed, the museum’s historian. “Before that, the Navy, despite accepting thousands of airplanes into service during World War II, had saved very few of them.”

A and T Recovery got contracts from the Navy to retrieve more planes. “It’s not about the money,” Lyssenko said. “These aircraft represent a story of us, the people of the United States of America. It took people from all over the country to build these planes, to train to use them, to take them across the ocean to go to war in them. People from all walks of life. These aircraft continue to tell that story of us.”

Over time, the recovery contracts became more specific. The Navy wanted planes of historical significance that eventually could be displayed not just in Florida, but in museums across the country. And they wanted them in restorable shape. Lyssenko would videotape the wrecks on the lake floor, fill out condition reports and send them to the Navy for a yes or no answer.

On one of its wish lists, the Navy wanted an SBD-1 Dauntless. That was the dive bomber’s first variation, built by the Douglas Aircraft Co. in about 1940. Because it had a limited fuel range, the Navy ordered modifications, and only 57 of the SBD-1s rolled off the assembly line in El Segundo. Several were damaged or destroyed at Pearl Harbor, and some were used on scouting missions in the Pacific, but my mid-1942, most were back in the United States, used for training.

“As the earliest version of the airplane, it is significant,” Goodspeed said. “It tells an important part of the overall story.”

The SBD-1 that Lyssenko went hunting for, bureau number 1612, was the 17th one built. Herbert McMinn was flying it when he disappeared on that Saturday in November of 1942.

Navy records Lyssenko reviewed included a written statement from a businessman who was standing near the lake at about 11 a.m. He said he saw a plane glide down to the water — “It looked as though it was a perfect landing,” he wrote — and then sink. He surmised the engine had quit because he didn’t hear it as the plane descended. The businessman included the street address near where he was positioned and estimated the plane had gone down about five to 10 miles out.

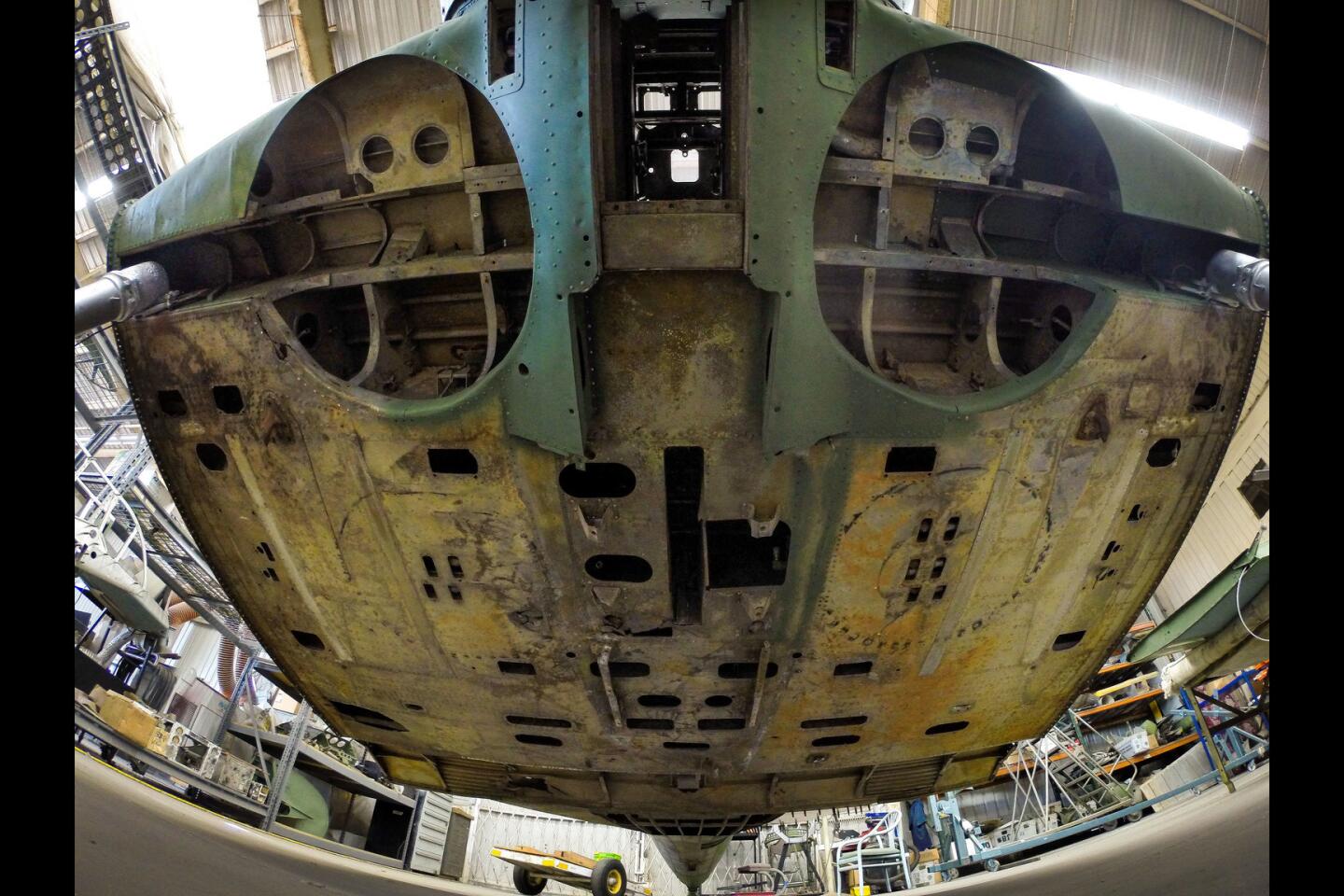

And that’s pretty much where they found it, on March 29, 1994. The bomber was in 50 feet of water. It was upright, clearly damaged, but mostly intact. There was no sign of the pilot.

‘I like challenges’

Navy officials looked for a museum with the interest, money, equipment and staff to restore the Dauntless so it could be displayed to the public. It went first to the USS Alabama, a battleship museum in Mobile, and then to the Midway Museum on the Embarcadero. In 2012, the Midway traded it to the Flying Leatherneck Museum for another plane.

Located adjacent to to Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, the Leatherneck Museum was keenly interested in the SBD-1. After the Navy rejected that variation because of range limitations, it gave the planes to the Marines. The one pulled from Lake Michigan, museum officials believe, is the only one remaining.

It arrived in pieces.

Cramsie heard about the project and volunteered. The 63-year-old Rancho San Diego resident saw it as a way “to give back to the community, to say thank you to the military.” He’s spent his career working around airplanes, first as a mechanic at PSA, then Lockheed Martin, and now as a test technician for Northrup Grumman. The scars on his wrists from carpal tunnel surgery attest to the many hours he’s spent driving rivets and turning wrenches.

He grew up in Millbrae, next to the San Francisco International Airport, where he got bit by an aviation bug that never let go, although it has loosened its grip enough to let him pursue other passions, like restoring a 1949 F-1 Ford pickup. He studied aviation mechanics in junior college and later got bachelor’s and master’s degrees in aeronautical fields.

What he saw when he first encountered the Dauntless was a challenge. “I like challenges,” he said. “It’s almost like therapy for me.”

He calculates that he’s spent more than 3,000 hours on the restoration. Many of the missing parts he has to fabricate from pieces of sheet metal. He built and installed the vertical stabilizer, for example, and made from scratch the aft gun bay and doors.

There are SBD blueprints on a computer he consults when he needs to, and internet forums like the Warbirds Information Exchange that he visits occasionally for parts and advice. “It’s a giant jigsaw puzzle,” he said. “But it’s a puzzle that will be solved.”

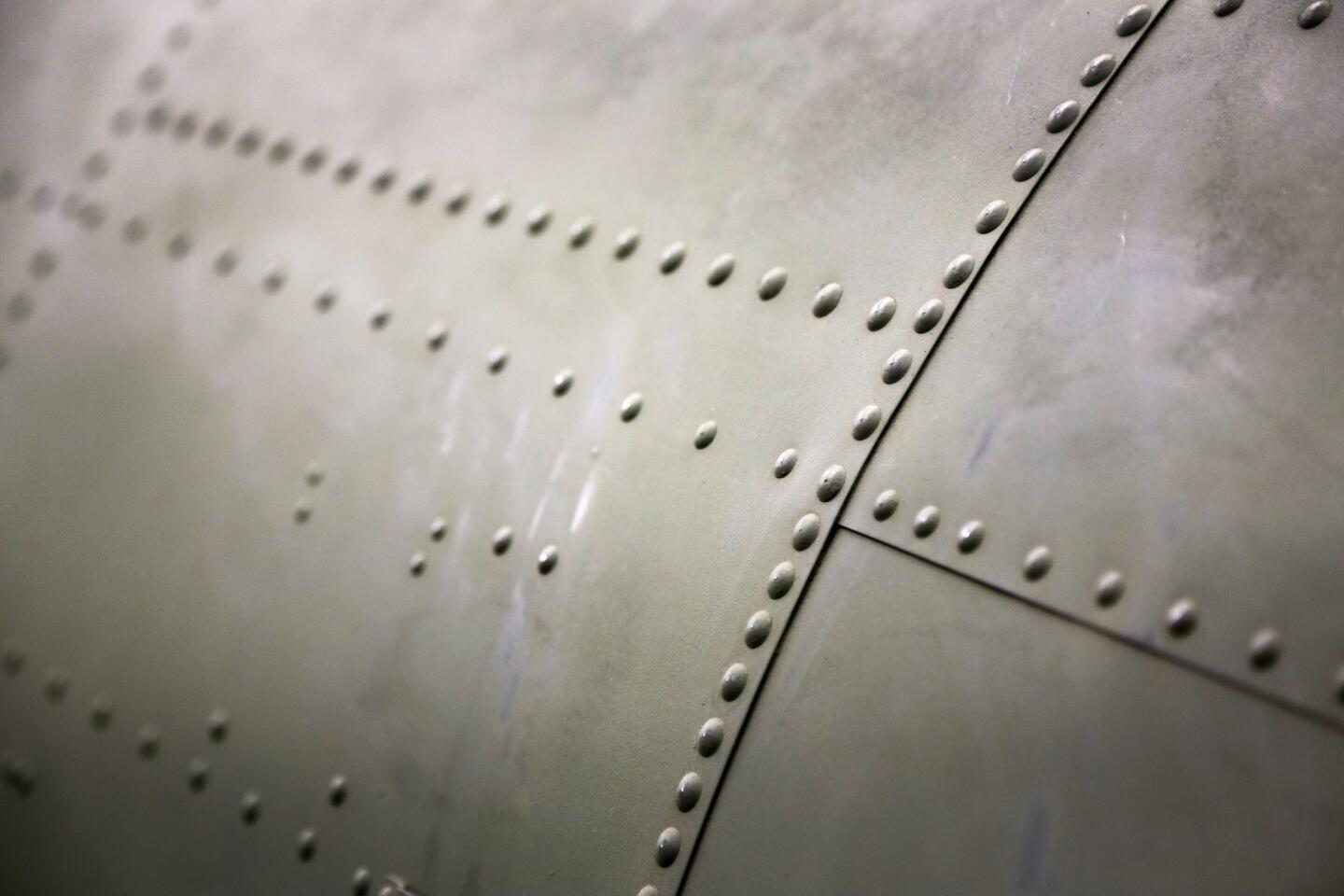

It’s important to him to be authentic. “As much as possible, nothing from Home Depot,” he said. “You’ll probably never see it, but I’ll know it’s there.”

The hangar where he works is cavernous. Several other aircraft are being restored there. The place tastes vaguely of metal, and when the compressors are running, it’s loud. Cramsie wears ear muffs.

One recent afternoon, he was piecing together the right wing with rivets. First he attached temporary fasteners to hold the metal skin in place; they made the wing look like a porcupine with its quills extended. He used a drill to make sure the holes were lined up correctly, then went to work with a rivet gun and a bucking bar.

It was hot in the hangar, and within minutes his dark blue shirt was wet with perspiration. He set down the rivet gun, took off the ear muffs and quipped, “Now just do that a few thousand times and you’re done.”

He’s had other volunteers help him, but they tend to come and go. At the rate he’s working, he said it will probably take him another four years to finish. A display board on an easel at the front of the plane shows what it will look like then: Wings painted yellow on top, machine guns in place, military insignia on the fuselage.

It will all be worth it, Cramsie said. Even though he’s never served in the military, he understands something about sacrifice. One of his uncles was a pilot in World War II whose A-20 Havoc went down in the English Channel while returning from a bombing mission on the day after Easter in 1944. No bodies — he had two gunners with him — were ever found.

No plane, either.

Reaching out

A few months ago, Lyssenko went looking for the relatives of Herbert McMinn. He combed Census records and found McMinn’s sister, Thelma, and then her son, Joe Lynch — both now deceased — and then Joe’s son, Bryan, who is the chief technology officer for a medical-device company in Houston.

Lyssenko sent Bryan Lynch a request to connect on LinkedIn. When Lynch accepted, Lyssenko messaged: “I located and recovered your great-uncle’s aircraft.” He sent links to some of the Navy documents about the disappearance.

Lynch messaged back: “Wow! I had no idea!”

He remembers his dad talking about how Uncle Herbert had been training on an aircraft carrier in the Great Lakes, “and that’s the last we ever heard of him. It was devastating to my great-grandparents, to my grandparents, to the whole family. There was never any closure.”

And now there is.

Lynch met with Lyssenko in person in late July. He saw photos of the plane after it was pulled from the lake floor. He learned about the Flying Leatherneck Museum and Cramsie. “It’s pretty amazing,” Lynch said. “I think the only sad part is that all of the people who really wanted to know what happened are gone.”

He looks forward to seeing the Dauntless. He’s a pilot, too, as was his father. And, of course, his great-uncle.

“From what I understand now, he did a good job landing it on the water,” Lynch said. “He may have had fuel issues, or maybe he was coming in for a landing and got waved off, but he did the best he could. He landed it square.”

There’s talk of a ceremony at the Leatherneck Museum, next to the Dauntless, to honor the last person who flew it. Lynch would be there. Lyssenko, too, and Cramsie. There might be speeches from Navy brass, and the display of family photos, and if all goes according to plan, some music.

Played on Herbert McMinn’s violin.

john.wilkens@sduniontribune.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.