Climate policy’s twin challenges

- Share via

Climate change presents two distinct problems. The first is linear: A little more warming causes a little more damage. The second is nonlinear: A little more warming pushes some part of the climate system past a tipping point and the damage becomes catastrophic.

We need smart climate policies that address both problems, so we can slow incremental damage while also taking out an insurance policy against the growing risk of catastrophic damage.

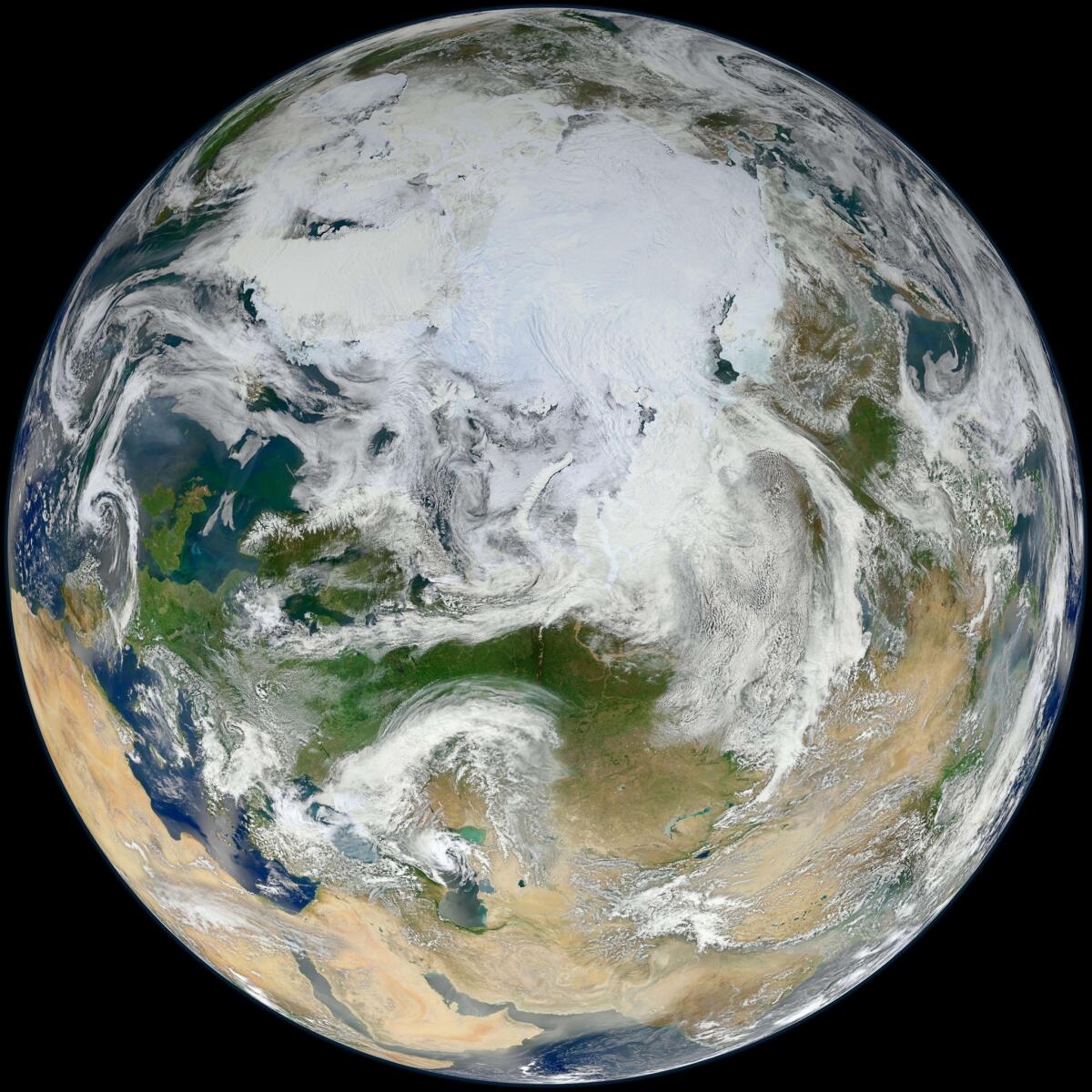

The Arctic is a prime example of a potential tipping point. It is already warming at twice the global rate, with Arctic sea ice disappearing faster than previously predicted. Some scientists calculate that it could disappear for all practical purposes later this decade.

The disappearing Arctic sea ice has set off a dangerous feedback loop — warming that feeds on itself — as dark heat-absorbing water replaces the white ice that used to reflect heat back to space. The warming has already pushed the southern limit of Arctic permafrost north by as much as 80 kilometers in Russia and 130 kilometers in Quebec.

Now a study in Nature reports that the world could face damage of $60 trillion if methane, a super greenhouse gas, escapes the bonds that hold it in place in the Siberian permafrost bordering the warming Arctic. This “permanent frost” may no longer be permanent. While this scenario is a low-probability risk, the consequences of a sudden methane escape would be overwhelming. And this is just one of many potential climate tipping points.

Climate policy must therefore include fast-action strategies to reduce near-term warming and to forestall potential tipping points, while also reducing near-term damage. This requires cutting the short-lived climate pollutants, including black carbon soot, which traps heat as an aerosol and also darkens snow and ice when it washes out of the atmosphere, causing the snow and ice to absorb more heat and melt faster. With its one-two punch, black carbon is responsible for half of Arctic warming.

It also requires cutting the other short-lived pollutants, specifically hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, methane and tropospheric ozone, the primary component of smog. Precisely because these four pollutants are short-lived in the atmosphere, cutting them reduces warming quickly, a vital attribute.

Success here could cut the rate of warming in the Arctic by two-thirds in a matter of decades. It also could cut the overall rate of global warming by half, while saving millions of lives every year now lost to these pollutants, reducing crop damage and slowing sea-level rise.

These strategies could be implemented immediately with existing technologies, laws and institutions, in most cases. For example, the Montreal Protocol, widely regarded as the world’s most successful treaty, could be expanded to cut HFCs, a strategy originally proposed by the Federated States of Micronesia and other vulnerable islands and now supported by more than 100 countries. President Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed to this approach at their California summit in June.

For black carbon and tropospheric ozone, the policy must start with national air pollution laws — the equivalents of the U.S. Clean Air Act. China, for example, just announced an aggressive $277-billion, five-year effort to cut its air pollution. Regional agreements also can play a strong role. Methane is a valuable fuel, and there are programs to help cities, companies and countries capture and use it, including the U.S.-led Global Methane Initiative.

To reduce the risk of setting off a methane time bomb in the Arctic and passing other tipping points for irreversible and potentially catastrophic climate damage, it is necessary to reduce long-lived carbon dioxide as well as short-lived climate pollutants.

Reducing short-lived climate pollutants can mean quick reductions in warming, whereas far slower but crucial cooling comes from cutting carbon dioxide, the principle greenhouse gas responsible for half or more of all warming. A substantial portion of carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for thousands of years, which means that cutting it today doesn’t produce much cooling for the first 50 years. Both kinds of reductions are essential for success.

Obama’s Climate Action Plan contains core strategies for pursuing both fast-action mitigation from reducing short-lived climate pollutants and long-term mitigation from carbon dioxide reductions. He’s made phasing down HFCs under the Montreal Protocol a top priority and, with Vice President Joe Biden and Secretary of State John F. Kerry, is pursuing this at the highest geopolitical level, something unique in the annals of international climate policy.

The challenge now is to encourage Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to join the agreement between China’s Xi and Obama to use the Montreal Protocol to cut HFCs. This would secure the biggest, fastest climate mitigation available to the world in the near-term. It also would build political momentum for reducing other short-lived climate pollutants, as well as for a successful U.N. climate agreement in 2015. Equally important, it would demonstrate what can be done when international climate policy moves to the head of state level, where it belongs.

Durwood Zaelke heads the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development in Washington and Geneva, and co-directs a related program at UC Santa Barbara. Paul Bledsoe is senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, and was communications director of the White House Climate Change Task Force under President Clinton.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.