Newton: A tale of two tax plans

- Share via

In a state where Republicans have all but disappeared from decision-making, this is what constitutes a debate today: Two leading liberals are arguing over how best to raise taxes to rescue the state from its economic and social decline.

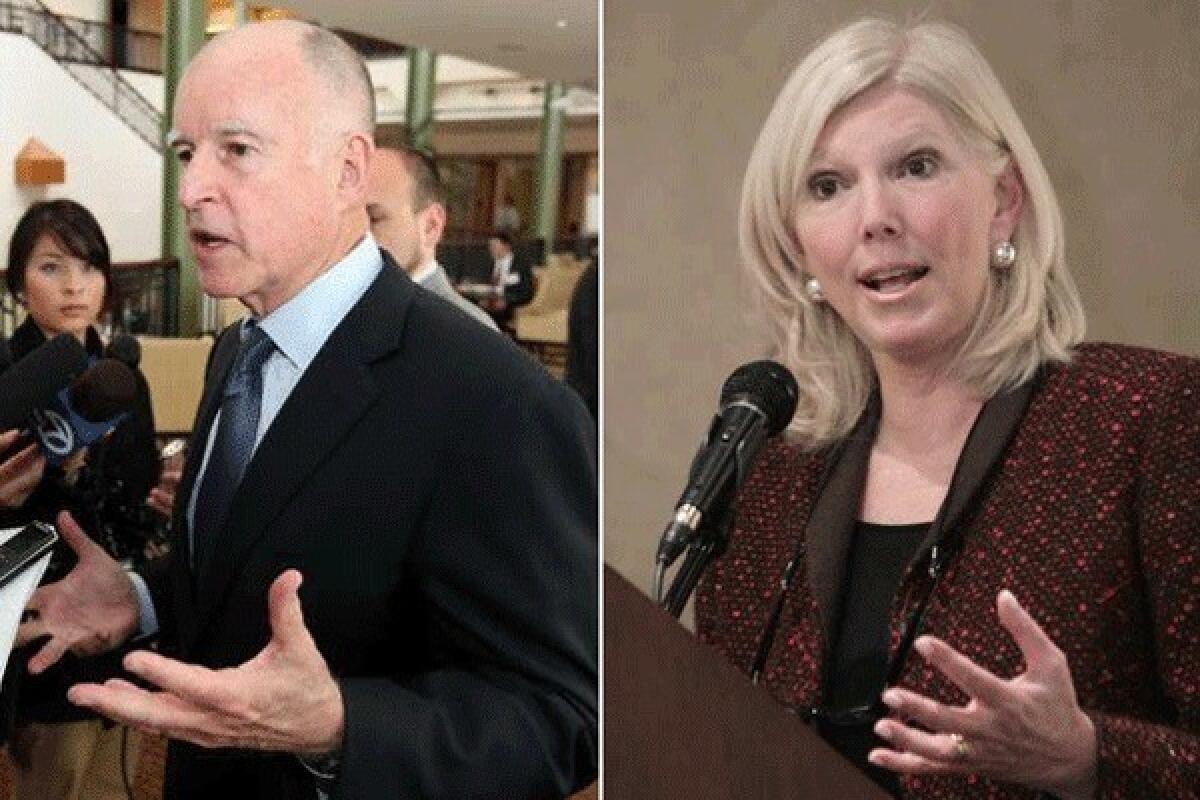

Gov. Jerry Brown, faced with a multibillion-dollar state shortfall, has joined with some of the state’s leading unions to urge Californians to approve what he calls a “millionaires tax” that would help patch up the state’s alarming budget gap, which still exists despite billions in cuts to state spending. Meanwhile, Molly Munger, an attorney who heads the Advancement Project and has a sizable fortune, is pressing ahead with a tax proposal of her own, one that would help alleviate the state shortfall but that is principally targeted toward reversing the decline in California schools.

Conventional wisdom is that each measure hurts the other; that Californians, if confronted with a pair of proposals to raise taxes, will either reflexively reject both or split their votes between the two, giving a majority to neither. Those Californians who choose one proposal over the other will also be selecting between two curious icons: a governor who got his start in politics thanks to his father, Gov. Pat Brown; and a stubbornly principled advocate who has money to spend on an initiative thanks in part to the family wealth created by her father, Charles Munger. Both Brown and Molly Munger are committed liberals, and both are tougher than they look.

“It’s awkward for friends of both of them,” political consultant Bill Carrick remarked to me last week. “I want the governor to succeed, but Molly’s put a hell of a lot of time into this, and her proposal is well thought out.”

Both measures start with the recognition that California is deeply in debt and that even years of cutting haven’t brought it into balance. Brown would address that shortfall with a combination of a sales tax increase and a tax hike on income of more than $250,000 a year. In economic terms, that’s not an ideal approach. It increases the tax burden on the poorest Californians, who pay a greater percentage of their incomes in sales taxes and who can least afford to pay higher taxes, and the richest Californians — those whose incomes gyrate most wildly with the economy and thus contribute to the instability in the state’s revenue collections.

Munger’s proposal, by contrast, avoids sales taxes altogether and boosts state income taxes by 1% across the board. That still means that high-income taxpayers would shoulder most of the burden because the income tax is progressive, but they wouldn’t shoulder all of it. And taxpayers at all levels would have to chip in. That’s more stable and more widely distributed than Brown’s plan.

When it comes to politics, the two plans also differ, though in ways that make it hard to predict which, if either, is likely to prevail.

Brown’s plan has the advantage of focusing its burdens on the poor, who don’t vote much, and the rich, of whom there aren’t very many. So a defect of the plan in terms of its economics is in fact a bonus for its political prospects. Moreover, Brown’s plan has Brown. “He’s obviously very articulate … and a great debater,” said Carrick. “He has the capacity to get the state megaphone and use it.”

Munger doesn’t have that sort of bully pulpit, but she’s tenacious and determined. We met recently at the California Club — where better to discuss taxes than surrounded by reminders of California’s bygone affluence, with a couple of members of the state’s elite playing dominoes in the next room? — and she shuffled through her stacks of statistics and analyses. Munger’s pitch is simple: California’s educational system is tragically broken, and voters, even voters who don’t usually like taxes, have said they are willing to pay something to fix it.

“This is a winner,” she said. “This is a window in which voters are willing to consider this. We need to take them up on their willingness.” To fail to let voters consider this measure when well over half say in polls that they would support it, Munger passionately added, “would be public policy malpractice.”

That’s a good message, and ads for the initiative already are on television. Early polls suggest that the initiative enjoys solid support, though by no means enough to guarantee its success — most initiatives need to start at 60% or above to withstand the campaigns against them and the voter impulse to respond to confusion by saying no. Both Munger’s and the governor’s are polling right about at that level.

One of the smartest people I know on the subject of California government was wary of commenting about all this on the record but worried that the coming collision of Brown and Munger may hurt them both. “Voters will look at this and see ‘tax increase vs. tax increase,’” this person told me. “You can’t split hairs on that with voters.”

Munger’s not so sure, nor am I. These are distinctly different approaches to addressing what by now should be universally recognized problems. Either would make life better. The tragedy would be if both lost.

Jim Newton’s column appears Mondays. His latest book is “Eisenhower: The White House Years.” Reach him at jim.newton@latimes.com or follow him on Twitter: @newton_jim.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.