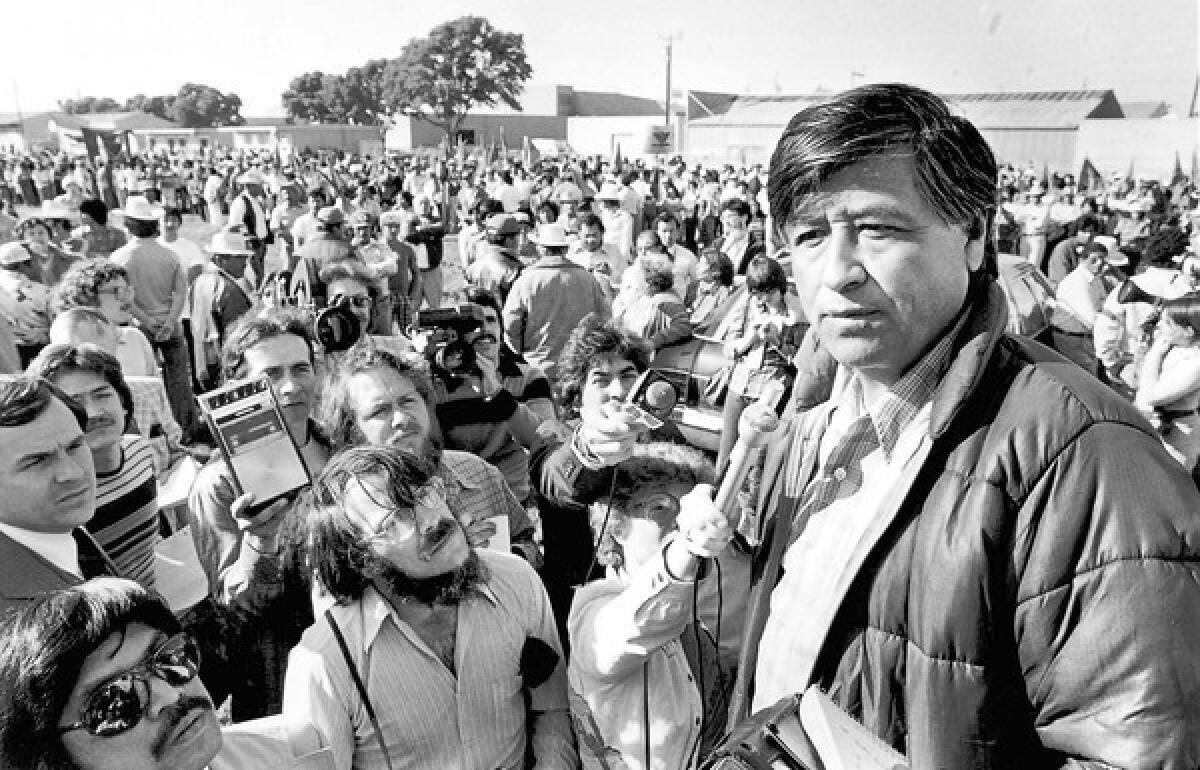

Cesar Chavez, flawed hero of the fields

- Share via

Cesar Chavez died in 1993, but the Mexican American labor leader’s prominence continues to grow. Streets in many American cities bear his name; his face appeared on a postage stamp; President Obama embraced Chavez’s slogan, “Sí, se puede” (“Yes, it can be done”) in his 2008 campaign; and Apple featured the United Farm Workers founder in its “think different” campaign.

These honors have all served to heighten public awareness of Chavez, who for a time seemed to be winning the battle to bring justice to the farm fields of California. But they have obscured another part of his legacy, one of miscalculation and failure. That legacy is also important to consider as the UFW celebrates its 50th anniversary this month.

For more than a decade, starting in 1962, Chavez fought against the odds to achieve union recognition for farmworkers in California. In 1975 the UFW achieved collective bargaining rights for these workers under the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act. The act, often touted as “the best labor law in the land,” created a state-run Agricultural Labor Relations Board that oversaw union elections and settled disputes between employers and employees. Such state-sanctioned justice for farmworkers presented Chavez and the UFW with a pathway to becoming the nation’s strongest union representing those who work in the fields.

At first, the UFW seemed destined for success, with a multiethnic coalition that included farmworkers, clergy, students and other labor groups. After the movement succeeded in persuading many consumers to boycott grapes from California and Arizona, growers were persuaded to sit down at the bargaining table and politicians jumped in to enact reforms. In his most recent election, California Gov. Jerry Brown held up creation of the ALRB as the signature achievement of his earlier terms as governor and as a reason why Latinos should trust him.

So, why is it that conditions on farms in California today still resemble those that existed before 1962?

Although the UFW and its advocates point to many reasons, few have been willing to give any of the blame to Chavez for his failure of leadership. To be sure, the ALRB had its problems, including inadequate funding and some political appointees to the board who opposed the union. Yet, by 1976, the UFW had won more elections than it had lost, and its legal team had cleared the way for more gains by reaching an agreement with its rival union, the Teamsters, to leave fieldworkers to it.

In spite of these achievements, Chavez turned away from the goal of organizing workers to concentrate on building a community at the union’s Kern County headquarters, La Paz. Chavez fashioned his “intentional community” in the likeness of Synanon, a cult-like drug rehabilitation program that demanded obedience to the leader, Chuck Dederich. Although many executive board members and veterans of the boycott stepped in to prevent Chavez from turning the UFW into a cult, his decision to abandon organizing at a critical moment, concentrating instead on the union’s hierarchy, prevented him and the union from realizing their full potential.

Acknowledging Chavez’s faults is quite difficult for consumers of his popular image. But many of the movement veterans I have interviewed in recent years acknowledge their former leader’s mistakes, including his failure to take the advice of his advisors to create a structure of governance that made him accountable to the workers he represented.

As one former member told me, Chavez was no “plaster saint” — colorful and noble on the outside, hollow and devoid of substance on the inside. He dealt with complex problems that sometimes led to destructive emotions, including frustration, fear, anger, conceit and even vengeance. And Chavez, like many other leaders before him, was unable to rise above those feelings or channel them into the creation of a stronger organization.

For those who seek to learn from the past, his story offers lessons about the very nature of leadership. Ultimately, understanding Chavez as a tragic hero rather than a saint is essential to analyzing what went wrong with the UFW, and to avoiding the mistakes of yesterday in trying to make conditions in today’s farm fields more humane.

Matt Garcia is director of the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies at Arizona State University and the author of “From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.