Op-Ed: 25 years after Rodney King, video still isn’t enough to stop police brutality

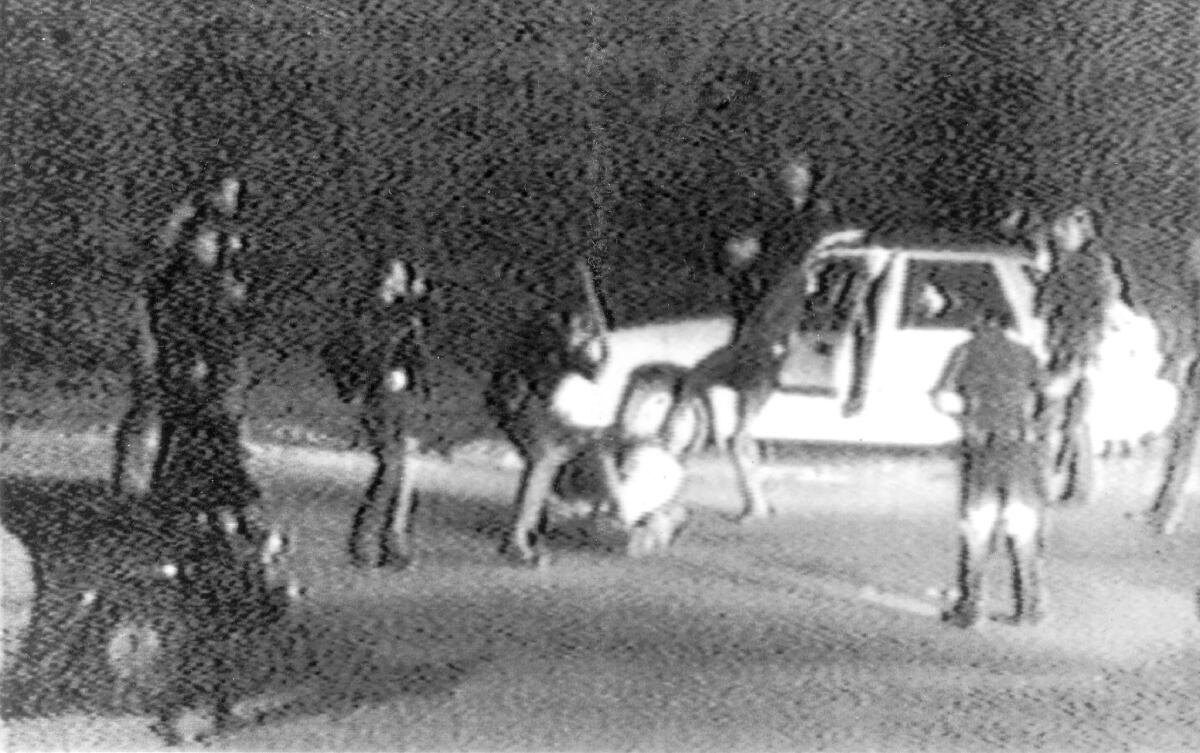

A still image taken from George Holliday’s 1991 video shows police officers beating a man, later identified as Rodney King.

- Share via

The rapper KRS-One famously posed this question to law enforcement: “Who protects us from you?” Exactly 25 years after Los Angeles police officers beat up Rodney King near a 210 Freeway offramp, the answer is the same as ever: The camera does, but only to a point.

On March 3, 1991, George Holliday, armed with an analog video camera, recorded King’s brutal treatment at the hands of at least four members of the LAPD. Local news aired the video that night, and soon CNN and other networks began to broadcast it across the nation. At once, America bore witness to what black folks have known since Reconstruction: “Law enforcement” has a much crueler meaning for citizens of a darker hue. Outrage bubbled beneath the surface of this national witnessing, and this outrage erupted when the criminal trial against the officers ended in acquittal.

We all watched the same video, yet 12 jurors (10 white and two people of color) could not agree that King’s rights had been criminally abrogated. The ensuing 1992 Los Angeles riots, one of the 20th century’s most destructive insurrections, resulted in 50 deaths, some 2000 injured and more than $1 billion in property damage. But that insurrection should not be remembered simply as an impulsive response to the King verdict; it was a reflection of the ongoing repression of black liberty.

Twenty-five years later, it is difficult to convey the potency of the Holliday video — seeing it now in its grainy glory belies the vivid influence it had on our collective conscience. I was an undergraduate in the South when the video first circulated. The clip radicalized me politically and existentially; it made me understand that any encounter that I might have with law enforcement could end in death. I remain resolute in this belief.

Many of the leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement were not yet born when Holliday began recording, but they too are intimately connected to that watershed moment. The Holliday video, its viral circulation and even the subsequent outrage in the streets of L.A. foretold our moment in protest.

Black Lives Matter activists triumphantly embrace a radical politics of the present. We need change now, they say. And they mean it.

Cellphone footage of Eric Garner in Staten Island, N.Y. — who died after a police officer put him in a chokehold — and Walter Scott in North Charleston, S.C. — shot in the back after a traffic stop — recalls Holliday’s visual document. We can all be George Hollidays now: Our cameras are smaller, better, faster. For the foreseeable future, we’ll wonder if the intermittent onslaught of snuff videos will dull our senses, make us numb, but the power of the camera (in the hands of civilians) in the ongoing struggle for equal justice under the law is unquestionable.

In the contemporary moment, not only can everyone with a smartphone become a George Holliday, but they can also become their own PR firm. Savvy activists like those associated with Black Lives Matter can distribute documentary evidence to more viewers than your favorite cable news station ever could. In many instances, the Hollidays of today use their capacity to circulate content via social media to pressure networks and news outlets to cover the stories (and atrocities) that matter to the movement.

Yet today, just like 25 years ago, video evidence isn’t enough; the U.S. criminal justice system resists indicting, much less convicting its own. The cops who beat up Rodney King were initially acquitted; the cop who put Eric Garner in a chokehold was not even indicted; the cop who shot Walter Scott in the back is out on bail, awaiting trial. There’s a vast gulf between awareness and substantive change.

Fully aware of that gulf, Black Lives Matter activists have begun an aggressive campaign to disassociate the movement from the establishment — whether that’s the Democratic Party, the black church or well-known civil rights activists. The establishment — even the establishment on the left — has for too long been invested in the kind of incremental progress that was championed by civil rights leaders. Black Lives Matter activists triumphantly embrace a radical politics of the present. We need change now, they say. And they mean it.

This decisiveness, which makes many uncomfortable with the project , might be the only possibility for both sustaining the movement and for making actual progress in eradicating the racial biases in our criminal justice system. A quarter-century from now, no one should have to explain that a video galvanized many, and changed little.

James Peterson is the director of Africana studies at Lehigh University, an MSNBC contributor and the host of the podcast “The Remix” at the Philadelphia NPR affiliate WHYY.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.