Op-Ed: If IBM’s Watson had legs, it would jaywalk

- Share via

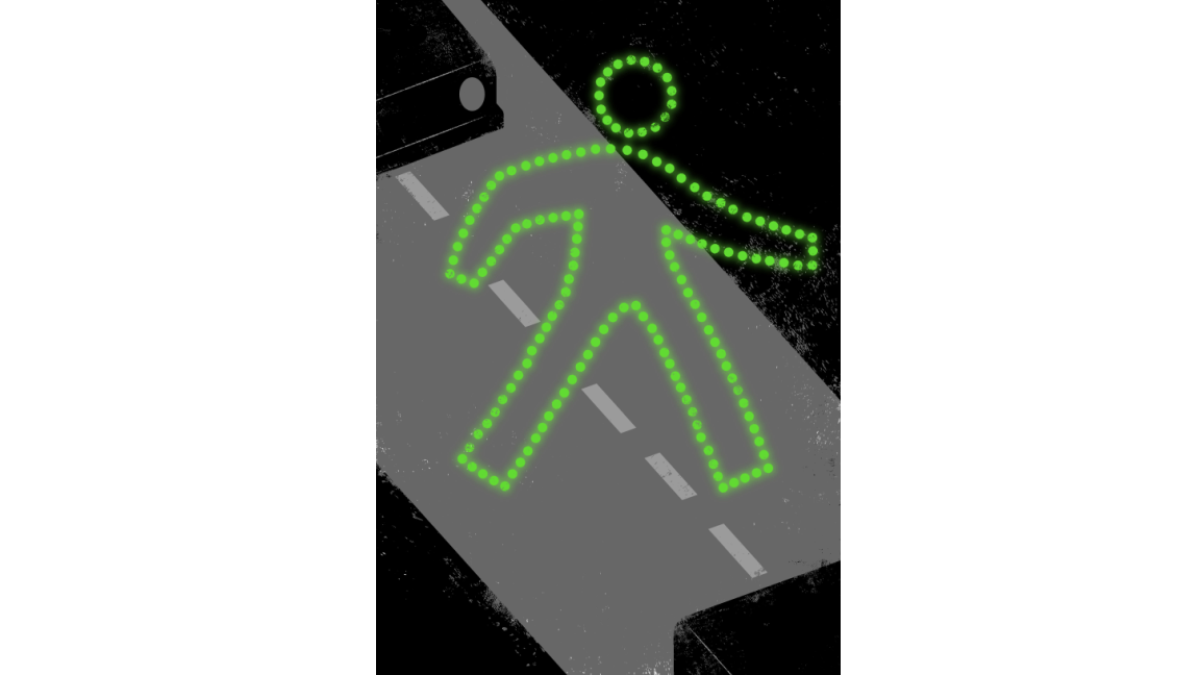

It’s strange to walk the streets of Seattle and San Jose, two of the world’s great software capitals, and see people behaving like machines. I’m referring to jaywalking or, more precisely, the lack of it. You see packs of knowledge workers huddled on street corners. They appear able to ignore the data streaming in through their eyes and ears that would make it clear to other creatures — dogs, squirrels or, for that matter, New Yorkers — that the coast is clear and it’s safe to cross. Instead they wait for a blinking machine to issue orders.

This approach, like much of computer science in its early years, is based on rules. Because cars are killing machines, they must stop at red lights. And because pedestrians can be killed and maimed by cars, they too must obey the signal. To save a motorist and a pedestrian from a deadly rendezvous, authorities force both driver and walker to follow strict rules.

Computer programs, traditionally, feature long lists of such rules. If X happens, do Y. This is ideal for listing names in alphabetical order and countless other memory and logic tasks. But rule-based thinking is what makes computers so thickheaded. They struggle to adjust to change. The human brain, by contrast, adjusts almost effortlessly. It picks up changing context, is alive to nuance and adjusts to exceptions. This is why when someone tells us his name is spelled Ximenez, we shrug and accept it, while the spell-checker on the computer stubbornly insists on changing the X to a J. Rules, by their very nature, are dumb.

Researchers in artificial intelligence are working to overcome them. They program machines, such as Watson, IBM’s “Jeopardy” computer, to analyze evidence and to calculate the odds for the best response. This is what jaywalkers do. We carry out advanced analytics involving a host of variables: the perceived speed of the oncoming truck, our walking speed and the width of the street, the worst-case chance that the driver will accelerate or swerve, and our ability in such a scenario to run.

Now, there’s always a good defense for rules. Traffic authorities no doubt agree that human beings have fabulous brains, which are fully capable of looking left and right, drawing conclusions and crossing the street when safe. But many people are not using their brains for this important work. They’re talking on their phones, listening to music or fiddling with umbrellas. Some are drugged. Some are lousy at calculating their chances against oncoming traffic.

So the only way to keep them safe is to treat them like herd animals and bypass independent analysis with ironclad rules.

That approach certainly makes sense for governing vehicles, at least until the computer scientists make these killing machines “smarter.” But I’d argue that we people should be as free as possible to navigate our bodies as we see fit. That includes the right to cross an empty street against a red light.

And what about the people who walk obliviously into traffic wearing headphones or messaging on Google Glass? Where jaywalking is legal, or at least tolerated, they have a choice. They can either wait with the masses for the red light or pay attention. If they choose neither and wander into traffic, an angry motorist will honk at them or scream out the window or, in the very worst case, hit them.

This does happen. In the jaywalking hotbed of New York City, 168 pedestrians were killed last year, according to police. It’s a grave problem. Mayor Bill de Blasio vows to go after outlaw pedestrians as well as fast-moving cars and trucks. In Los Angeles, where 72 pedestrians died in 2013, the police justify handing out $250 tickets to people who step into crosswalks downtown as the “walk/don’t walk” signal begins to count down because of “too many accidents and deaths.”

Despite such crackdowns, jaywalking is a constant in most cities. It’s factored into our commuting and delivery schedules. It’s also part of what makes a city feel footloose. As the years pass, I think we’ll especially treasure this freedom of movement because in so many areas we’re going to be less free. Increasingly, governments, employers and insurance companies, among others, are going to have the tools to monitor and optimize our behavior, in every area from the dinner table and the workplace to our cars.

In fact, the same push for safety that punishes jaywalkers will likely lead us to driverless vehicles. They’ll be a lot safer, since automatic drivers don’t drink, text, turn around and scream at kids or fall asleep. At the same time, though, we passengers are bound to feel a bit shackled as the cars convey us, under the speed limit and following the most efficient route, to our destination.

At least we should be free to jaywalk. It will be a tiny refuge for self-expression. And here’s the best part. In this future, driverless cars will screech to a halt if a pedestrian crosses their vision. It will no doubt be programmed into their operating system as a rule.

Stephen Baker is the author of “Final Jeopardy: Man vs. Machine and the Quest to Know Everything.” His novel “The Boost” came out in May.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.