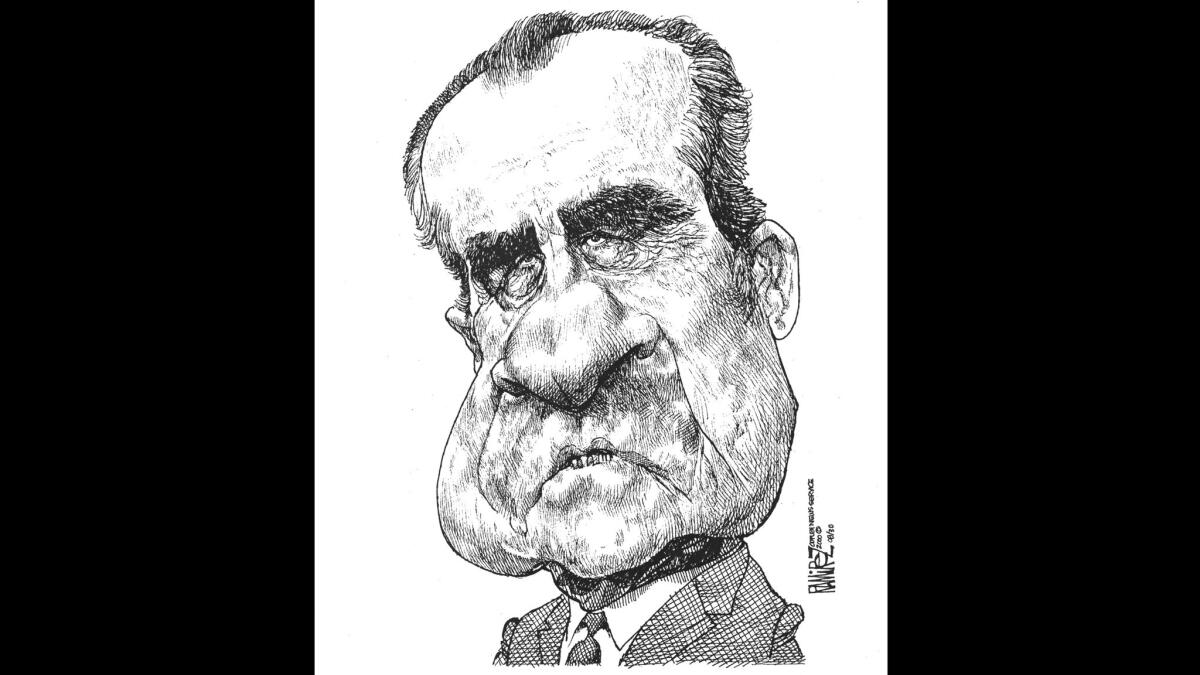

Op-Ed: Richard Nixon — upbeat sweetheart

- Share via

The image of Richard Nixon as scheming trickster, deeply embedded in the American psyche, is fed by Hollywood, comedy and the liberal media. And, it should be said, by historical truth: Nixon could be manipulative and cunning. He often used secrecy and duplicity in politics and statecraft. But there wasn’t just one Nixon; our most reviled president contained multitudes. There was the sweet Nixon, who could be tender and wanted to be upbeat; and the fearful, fretful Nixon, who confronted the Watergate scandal with confusion and politically fatal indecision.

Of his worst side, Nixon left us vivid evidence: the White House tapes. There is a reason Nixon spent millions of dollars in legal fees in a vain effort to keep them under wraps. They make him seem mean, petty and bigoted. At least some of them do.

On many of the 3,700 hours of tape, Nixon comes across as shrewd, commanding and arrogant. In other instances he sounds fake and insecure. When he swears and blusters, Nixon seems to be showing off, pretending to be the macho man he really wasn’t. Once, when an advisor went on about curing global poverty, Nixon turned to another aide and stage-whispered, “Doesn’t it make you want to puke?” (For a revealing comparison, listen to Lyndon Johnson’s White House tapes. Nixon was never clever enough to say, as Johnson did, “I’d rather have him inside the tent pissing out than outside the tent pissing in.”)

Nixon often said he didn’t like talking to intellectuals (too “feminine,” he said), and that he preferred talking to athletes. This boorishness, however, was just pretense. A poor athlete, Nixon was himself an intellectual. He read widely and deeply; his many volumes of political philosophy and historical biography, which he underlined and starred, are at the Nixon Library. “No more Harvard bastards!” Nixon would exclaim. But when he was elected president in 1968, he hired as his two top aides a pair of Harvard professors, Henry Kissinger (national security) and Daniel Patrick Moynihan (domestic affairs).

Nixon resented the East Coast liberal media establishment, which he correctly believed was out to get him. As his ambassador to the Washington Post, Nixon sent Kissinger, who promptly sold out the president at Georgetown dinner parties hosted by the Post’s owner, Katharine Graham. Funny and self-deprecating, Kissinger made fun of Nixon’s social awkwardness. Nixon tried to be philosophical about Kissinger’s need to be popular with the swells, calling out, as Kissinger left the Oval Office in the evening, “There goes Henry to see his Georgetown friends!” But of course he was wounded.

Nixon ultimately did engage in a cover-up of Watergate, but only after telling his aides that the worst thing to do is cover up. Was he just cynically posturing? “But that would be wrong!” has become a kind of punch line.

It’s easy to see Nixon as a hypocrite, but he was hardly a criminal mastermind. Close attention to the Watergate tapes reveals a bewildered, uncertain Nixon, fumbling in the dark. He asks questions about the break-in and related crimes — there’s no evidence, contrary to popular belief, that he knew about these in advance — but again and again he backs off from interrogating his subordinates.

He particularly did not want to know the degree of involvement of John Mitchell, his former law partner, attorney general and head of the Committee to Re-Elect the President. Was the president protecting himself by practicing plausible deniability? Or — what I believe is more likely — was he too anxious to confront his old friend?

Nixon would say, “What if I ask him and he tells me he was guilty?” The proper answer, of course, would be to call in the prosecutor, but Nixon equivocated and dug himself in deeper. Nixon was well known among aides for ducking face-to-face confrontation. He never did take on Mitchell.

Often described as a fatalist and a pessimist, Nixon struggled to be an optimist. His daughter Julie recalled that when he came home at night, he would walk in the door whistling, turn on all the lights in the living room and put a show tune on the record player. He wanted the talk at dinner to remain light and upbeat. Late at night, he sometimes made notes to himself on his yellow legal pad (“his best friend,” his aides joked), using words like “joy,” “serenity” and “inspiring.” Nixon was describing the man he wanted to be, even if he knew he could not sustain those feelings.

For better and for worse, Nixon converted some of his insecurities into guile. How did someone so shy become one of the most successful politicians of the 20th century? Nixon made the most of being an outsider. At Whittier College, rejected by the cool kids fraternity, he started a fraternity for uncool kids — he knew there were more of them — and went on to be elected student body president. A conservative, Nixon was willing to compromise and cut deals with Democrats because he was so apprehensive about the possibility that they would outflank him. In fact, we probably owe the existence of the Environmental Protection Agency to his nerves; worried that Democratic Sen. Edmund Muskie would ride the environmental movement to the White House, Nixon one-upped him by creating a whole new department.

Nixon could be shifty and tricky; it is fair to describe Nixon as Machiavellian. But it is worth remembering that Machiavelli wanted his prince to be good.

Evan Thomas is the author of “Being Nixon: A Man Divided.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.