Op-Ed: How not to raise a workaholic

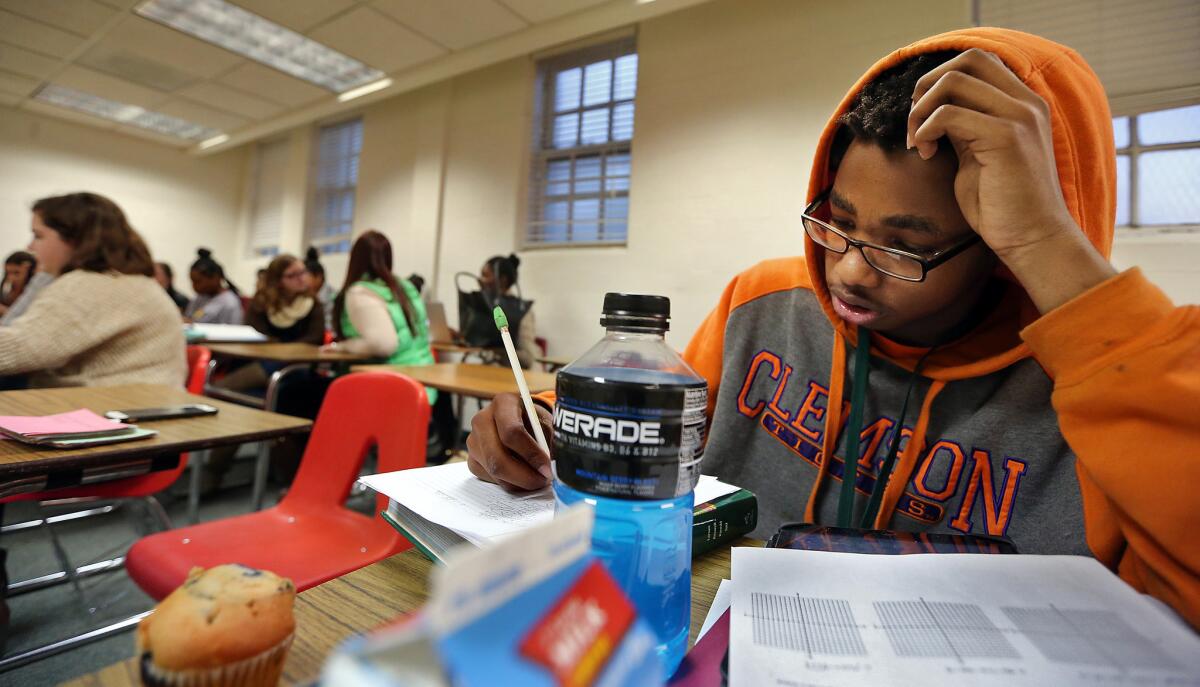

A student studies for an upcoming algebra exam at an after-school program in Charleston, S.C.

- Share via

When she was 13, my diligent daughter was assigned a science project on cell biology. She had to make up “families” of cell parts, complete with personality traits based on their functions. A clever idea, but it was impossible for Shelby to devote the deep thought it required amid all her other nightly schoolwork: studying for Spanish tests, reading history, writing essays, completing math problems.

The night before it was due, I found Shelby anxiously working away near midnight. She was far from done, but I bugged her to go to bed until she grudgingly turned out the light. In the morning, I discovered that she had woken up again at 3 a.m. to finish the project — even though she had to be at school at 7 a.m. for chorus practice.

We adults encourage kids to take on activities with good intentions ... [but] we are actually throwing the balance of their childhoods gravely askew.

I recognized that compulsion to work. In my first job as a lawyer on Wall Street, I sometimes stayed at the office for days at a time, barely sleeping or eating. I even landed in the hospital with a herniated disk from too much time at my desk. My daughter’s task-bound life was the same, except for an important difference: I was a young adult. Shelby was a child. Plus, I could, and eventually did, quit that job. She didn’t have that option.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Education researcher: An op-ed published Jan. 29 referred to Mary Helen Immordino-Yang as a neuroscientist at UCLA. She is on the faculty at USC.

------------

Demands on kids’ schedules have mushroomed in recent decades. Well-meaning adults — teachers to parents, coaches to tutors — cram children’s days wall-to-wall with obligations. Hard data on kids’ busyness is scarce, but in my travels as a writer and filmmaker to schools across the country, I’ve heard bewildered parents complain that they can’t persuade their 16-year-olds to stop working even for a weekend outing. Others say they rarely sit down to dinner with their 10-year-olds anymore, so great are a fifth-grader’s obligations. Even in preschools, research has found that children get only 48 minutes a day for free and active play. Only 8% of teens get the recommended nine or more hours of sleep.

We adults encourage kids to take on activities with good intentions, in the name of GPAs, college applications and future success. Yet we are actually gravely throwing off the balance in their childhoods.

School is already a 35-hour workweek for students. During the school day, an antiquated bell schedule keeps them churning from one quick class to the next, generating homework in as many as eight different classes per day. After the last bell, the continuing demands of take-home work, over-long practices or evening rehearsals gobble up the hours that belong to families — hours that children need to play, explore and rest to stay healthy and ready to learn.

Even families who try to slow down find it difficult to do so. Their kids are surrounded by peers with frenetic schedules, and the pressure of the insane race for college admissions feels inescapable. Organized activities, which are good for kids in moderation, tend to require massive commitments. Schools have the power to hit the brakes on many of these trends, yet most are still stepping on the gas.

In 2014, for instance, the California Interscholastic Federation capped time allotted to high school sports at four hours a day and 18 hours per week — which is better than having no limits, but still makes being an athlete a part-time job.

The pace afflicts not only students in elite suburbs, but also those for whom education is a ticket out of poverty. I met one such student while researching this issue in the rural town of Cadiz, Ky.: Summer Cottrell, a bright high school junior. Her parents didn’t go to college, and the college application stakes felt higher for her than for her more affluent peers. She was taking extra classes at the state university and participated in leadership club, drama and band. Band practice and performance alone sometime consumed 30 hours of her week.

The constant busyness affected her emotionally and physically, she said. “Most students say everything is fine and they don’t show the stress they feel,” she told me. “Under the surface they struggle with depression and anxiety and get sick a lot.”

To what end, this madness? Contrary to its intended purpose, our children’s lopsided school-to-life ratio is not readying them for success in life. It is instead creating a generation of tiny workaholics — burnt-out, stressed and paradoxically underprepared for the challenges of the post-academic working world.

For instance, children who spend more time in less structured activities (such as reading, drawing, free play or social outings) are better at setting and accomplishing their own goals than those whose pursuits were more scripted, according to researchers from the University of Colorado in Boulder.

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, a neuroscientist at UCLA, has found that when subjects’ minds are free to wander without any immediate task, they develop stronger memories, cognitive skills and social-emotional skills. Overprescribed school and home lives may also help explain the documented decline in measures of children’s creative thinking since 1990.

Restoring a sane school-life balance is the responsibility of everyone involved in kids’ lives: educators, parents, coaches and students. We should all take a serious look at a child’s 24-hour day and ask what it truly should contain. Surely health, rest and family time are high priorities. Then we can begin to ensure that our collective demands on children’s time align with what most matters.

A number of school communities have already begun these efforts.

At Burbank’s John Burroughs High School, a pair of mothers studied the scientific literature and, finding no link between excessive homework and school performance, drafted a resolution urging schools to rein in runaway assignments. The California PTA adopted their resolution statewide in 2014, and it’s under consideration this year by the National PTA.

At Irvington High School in Fremont, Calif., counselors sit down one-on-one with every student each spring and guide them toward a reasonable course load, discouraging them from taking on a crippling Advanced Placement load only for their transcript’s sake. And in Summer Cottrell’s school district in Kentucky, educators are creating longer class periods to imbue deeper learning at a more sensible pace.

Parents and educators tend to fear that less homework and more down time will make things “easy” for students, removing challenge, rigor and purpose from their academic lives. Let us free ourselves of that false notion. There are many ways to succeed in life and many paths to a sufficient and satisfying livelihood. None of them require childhood burnout.

Vicki Abeles is the author of “Beyond Measure: Rescuing an Overscheduled, Overtested, Underestimated Generation.” She also directed and produced the documentaries “Race to Nowhere: The Dark Side of America’s Achievement Culture.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.