Op-Ed: Ben Carson should approach HUD the way he did medicine: First do no harm

- Share via

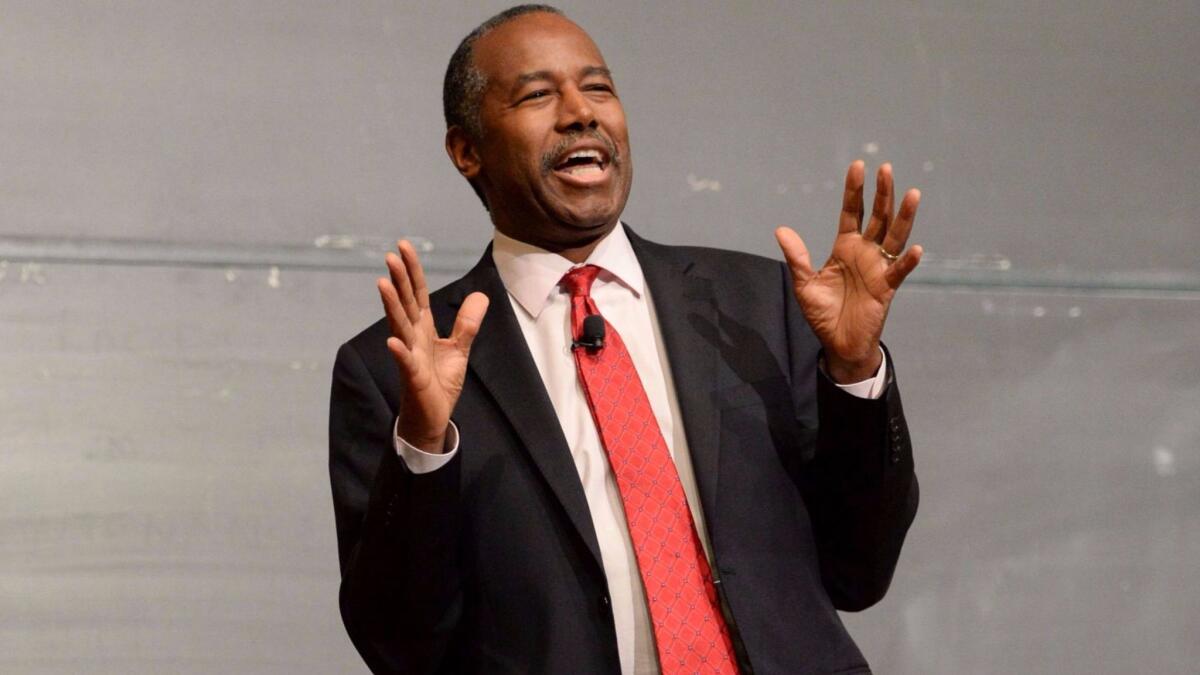

On Thursday, the Senate holds hearings to confirm Ben Carson as the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s new secretary.

As a physician, Carson had to abide by the Hippocratic Oath of ethics. The oath calls on doctors to remember the basic humanity of their patients and the ravages of disease on their economic stability. It reminds doctors to respect the knowledge of experts who have gone before and to emphasize the role of caregiver.

Carson should renew that oath if his nomination is confirmed and he assumes office at HUD.

The outgoing HUD secretary, Julián Castro, aptly characterized HUD as “the Department of Opportunity.” But HUD is also America’s Department of Mercy. As much as any part of the federal government, the agency works to soften the hardest edges of poverty for families, seniors and veterans. To preside over HUD is to support the life chances of more than 30 million vulnerable Americans.

How will [Carson] cut housing voucher and infrastructure programs that already turn away the majority of eligible people and communities?

At its heart, HUD is a safety net that provides emergency shelter, private-market housing vouchers and long-term housing for very poor seniors and families. It looks out for rural families as well as urban ones. Under President Obama, HUD led the effort that reduced veteran homelessness by 47% since 2010.

The department’s mission also goes beyond alleviating poverty. It is a mortgage lender, helping middle- and working-class families build wealth and stability through homeownership. In 2016 alone, its Federal Housing Administration helped more than 1.2 million Americans obtain mortgages to purchase a home, and its efforts have been central to easing the ravages of the foreclosure crisis that precipitated the recession of 2008.

When homes, communities and livelihoods are devastated by floods, wildfires or other natural disasters, HUD works with FEMA to help with the rebuilding. During Obama’s two terms, HUD invested more than $18 billion in disaster recovery efforts in California, Texas, Louisiana, the Northeast and other areas. With the intensifying weather extremes that characterize global climate change, this wing of the agency’s mission already faces new levels of strain.

Above all, the agency operates at the center of an issue that defined the 2016 campaign and election: the chronic adversity facing workers left behind by advanced manufacturing, the knowledge economy and global trade. Such workers live not only in Trump’s rural strongholds but in urban communities of color, like Carson’s hometown of Detroit.

HUD must be part of the new administration’s answer to that challenge, financing infrastructure to modernize poor communities. With investments in wireless access, sewage lines, lead abatement and neighborhood parks, HUD has been a linchpin of federal efforts to bring communities’ into the contemporary economy.

We know little about Carson’s and Trump’s housing policy positions, but their approach to taxes and to the safety net indicates that Trump’s HUD is likely to be defined by cuts across all of these programs. Before Carson is confirmed, senators should ask him the questions he will face over and over as the new president and the new Republican Congress assume control of HUD’s purse strings: Who will lose housing? How will he cut housing voucher and infrastructure programs that already turn away the majority of eligible people and communities?

If Carson fails to defend the beneficiaries of the agency he is tasked to lead, he will find himself in a position similar to that of President Reagan’s HUD Secretary Sam Pierce, who implemented nearly $20 billion in cuts to HUD’s subsidized housing programs. By the end of Reagan’s terms, nearly 10 million additional Americans had fallen below the poverty line and more than 2 million people had become homeless, despite rising federal spending overall and dramatic tax cuts for the wealthy.

Carson has said he wants to make HUD “a springboard” rather than “a hammock.” If he becomes the secretary of Housing and Urban Development, he will learn anew what he surely saw personally in his youth, watching his mother work several jobs: There is no hammock for those trapped in American poverty or homelessness. Indeed, a sick bed is a closer analogy. We truly hope that Carson will return to his doctor’s oath to “do no harm” to the people and communities who need HUD’s help to get by and then get ahead.

Michelle Wilde Anderson is a professor at Stanford Law School and Shamus Roller is executive director of the National Housing Law Project.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.