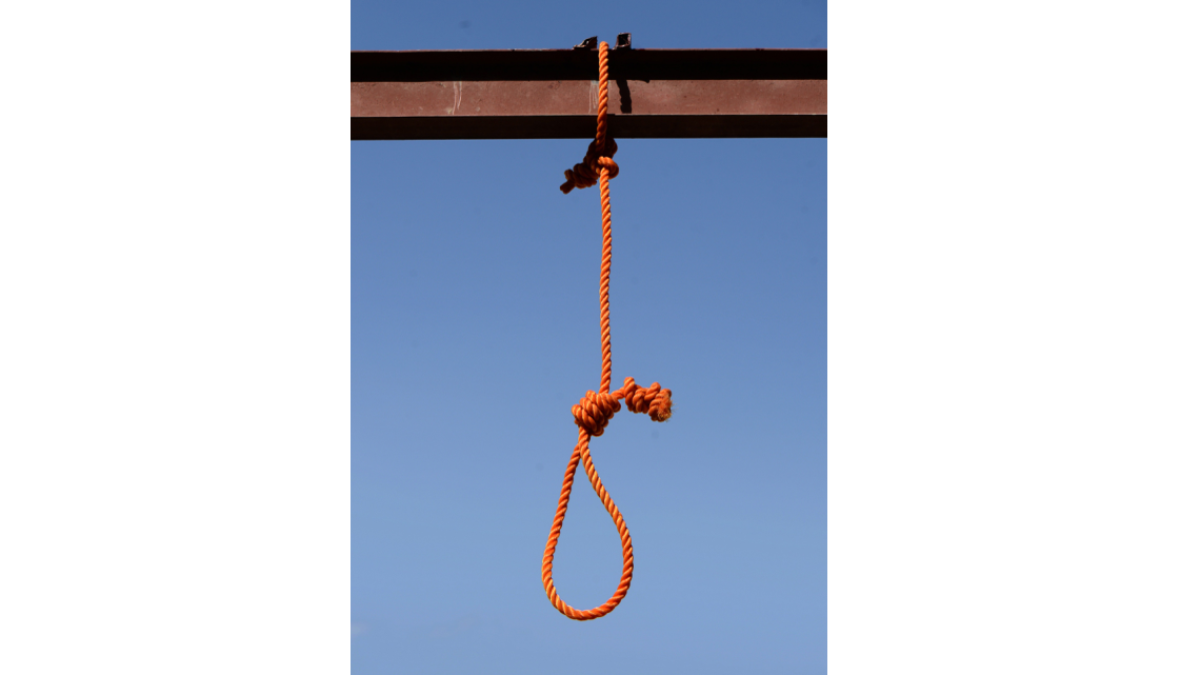

Op-Ed: The ominous symbolism of the noose

- Share via

Two nooses were found hanging at high schools in Los Angeles County on Oct. 15 and 16. At Bellflower High, the hangman’s knot was accompanied by graffiti declaring that God hates black people. At nearby Mayfair High, the noose wasn’t captioned, and a Sheriff’s Department sergeant told The Times, “A noose in itself is not making any correlation to anything.”

But is that ever true?

The hangman’s knot, a rope looped and secured with multiple wrapping turns or coils, probably was adapted from knots used in horseback riding, fishing and sailing. It looks a lot like a heaving-line knot, used by sailors to add weight to a rope thrown from boat to shore. Whatever its derivation, it was ultimately put to use hanging humans by the neck until they were dead.

Hanging has been a method of execution for thousands of years. In colonial America, on the Western frontier and well into contemporary times, records show that at least 9,324 people have been hanged legally in this country. In 1996, Billy Bailey of Delaware became the last to be executed by hanging.

The majority of those hanged, or executed by any means, were poor and racial or ethnic minorities. Of the approximately 15,000 people executed in all in this country, from 1608 to 2002, the top three occupations were slave, laborer and farmhand; 11% were slaves.

But it is extra-legal hangings that make the hangman’s knot especially ominous. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, an epidemic of lynchings swept the nation. At least 4,700 people — mostly men but also women and children — were brutalized, mutilated and hanged from trees, telephone poles and bridges across the nation. Some were Mexican American, Native American and even Irish, but three-fourths of them were African American. Lynchings were social events, documented in photographs like a day at a county fair. Look closely at the pictures (if you can stand to) and you’ll see, not always, but often enough, a perfectly tied hangman’s knot.

Mob lynchings dissipated after the 1930s, but the noose never died. It became a stand-in for vigilantism, for murder by community, an unveiled threat and a symbol to brandish to keep blacks, especially, “in their place.”

On May 3, 1939, in Miami, a Klansman held a hangman’s knot outside a car window during a “parade” through an African American neighborhood the night before a municipal election. In the late 1950s a noose was mailed to NAACP Secretary Roy Wilkins. And on Sept. 11, 1956, in Texarkana, Texas, a noose appeared, dangling in a schoolyard tree during a battle over desegregation.

In the 60 years since, the details of the back story may have faded for some, but the noose has lost little of its fearful power. I interviewed an African American man who found a noose on a time clock at the small manufacturer where he worked in Elwood, Ind., in 2010. When he saw it, lynching was the first thing that came to his mind.

“It’s almost like I could see myself hanging from that particular rope,” he said. “I had a vision, like I was in a movie or a photograph. And I saw myself hanging from a tree. Seriously! Me, hanging from a tree.”

In Jena, La., in 2006, white students hanged two nooses from a tree in the schoolyard. The white students were surprised by the horrified reactions from black students; they claimed they didn’t know the history of lynching — a history with deep roots in their home state. No matter: Jena was roiled by racial turbulence and division.

I’ve been tracking such contemporary incidents since 2010 and can account for almost 100 of them across the country. In October 2010, a few weeks after moving into a predominantly white neighborhood in Noblesville, Ind., an African American family found a noose in their yard. In the weeks before the 2012 election, some of the many noose incidents directed toward President Obama involved hanging chairs — a reference to Clint Eastwood’s GOP convention speech in which he addressed an empty chair representing the president. In April 2013, a black mayoral candidate in Meridian, Miss., found a noose hanging outside his office.

As late as 1981, the noose’s deepest roots were again unearthed. A black man named Michael Donald was found suspended from a tree in Mobile, Ala. He had been kidnapped, beaten, strangled and had his throat cut before he was hanged by two Klansmen to “show Klan strength,” according to the later testimony of one of the killers, James Knowles. In the courtroom, Knowles testified to the effort he put into cutting and sealing the ends of the rope and then tying the hangman’s knot, getting it just right. Knowles, then a teenager, knew exactly what the noose meant.

Perhaps the nooses hanging at Mayfair and Bellflower High Schools are more pranks than hate crimes, but American history offers one long denial that they “make no correlation with anything.” At the very least, they betray profound cultural ignorance; their true menace is clear. A Bellflower student got it immediately: “It’s honestly disgusting,” he told a TV reporter. “There should be ... no hatred between anyone. It’s wrong.”

Jack Shuler is an English professor at Denison University and the author of “The Thirteenth Turn: A History of the Noose.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.