Using old equipment, Oaxacan photographer Citlali Fabián records her even older culture

- Share via

There’s no way of knowing exactly how many Oaxacans live in the Los Angeles area — maybe 50,000, maybe 250,000. Since the 1970s, and even before, they have come, from one of Mexico’s poorest states, for the usual reason — work. But they’ve brought with them the richness of their indigenous cultures.

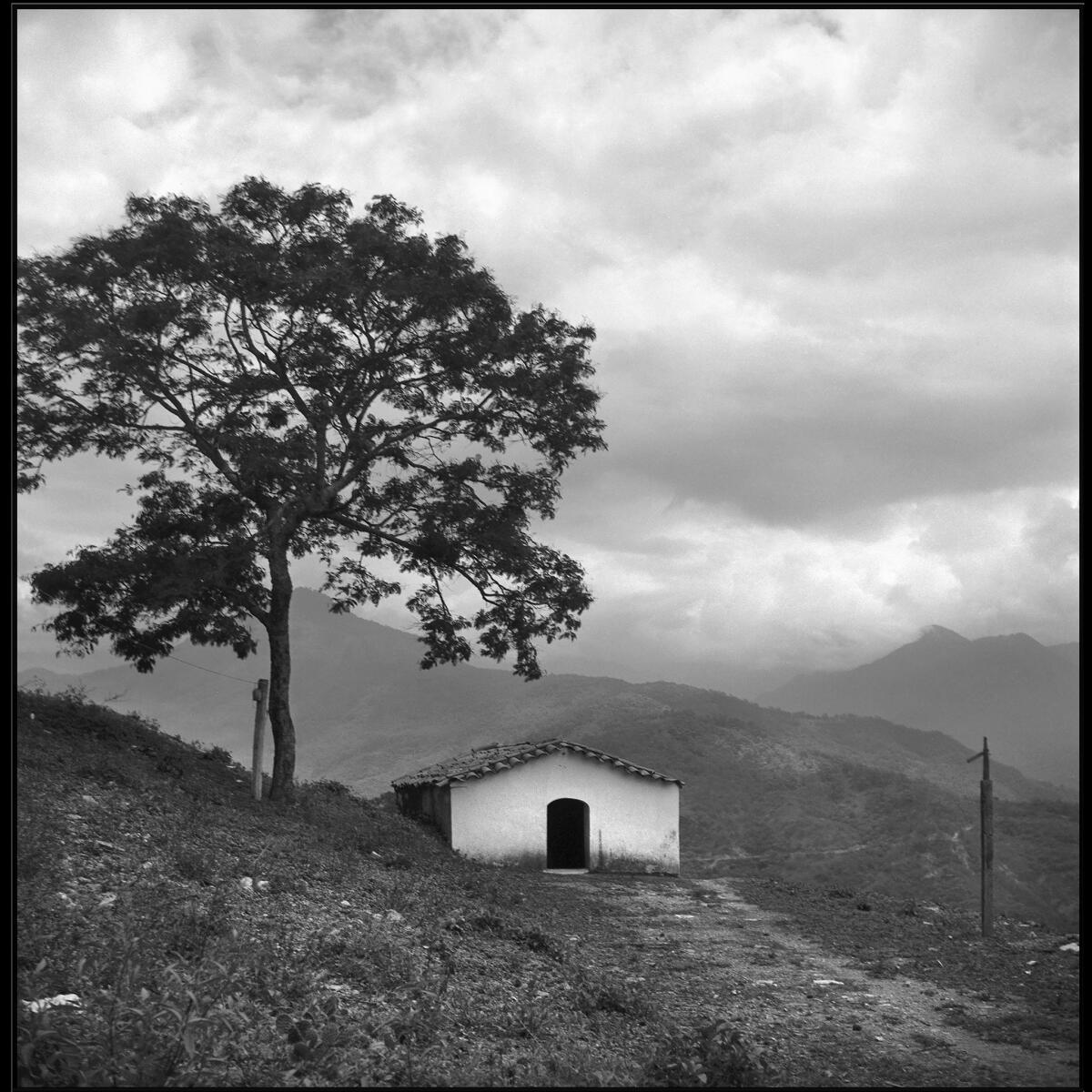

Citlali Fabián is one of their own, a Yalaltec Oaxacan, an artist whose medium is photography. She uses 19th century photo technology to make portraits like her “Mestiza” series, luminous images of indigenous women — including her own mother — whose faces could be out of the 16th century, from exactly 500 years ago, when Hernan Cortes conquered Mexico. Fabián and her odd old cameras just spent time photographing Oaxacans in Los Angeles, recording images for a sort of family album of the transplanted, pictures of one people making their lives in two countries, separated by an ever more impenetrable border but united by culture and centuries.

Click here for the full archive of "Patt Morrison Asks" podcasts »

What exactly brought you to Los Angeles?

My main interest is to document different aspects about the Yalaltec community. The Yalaltec community is an indigenous group from Mexico, and it has spread around Mexico, in Mexico City, in Oaxaca City, in Veracruz state, but also here in Los Angeles.

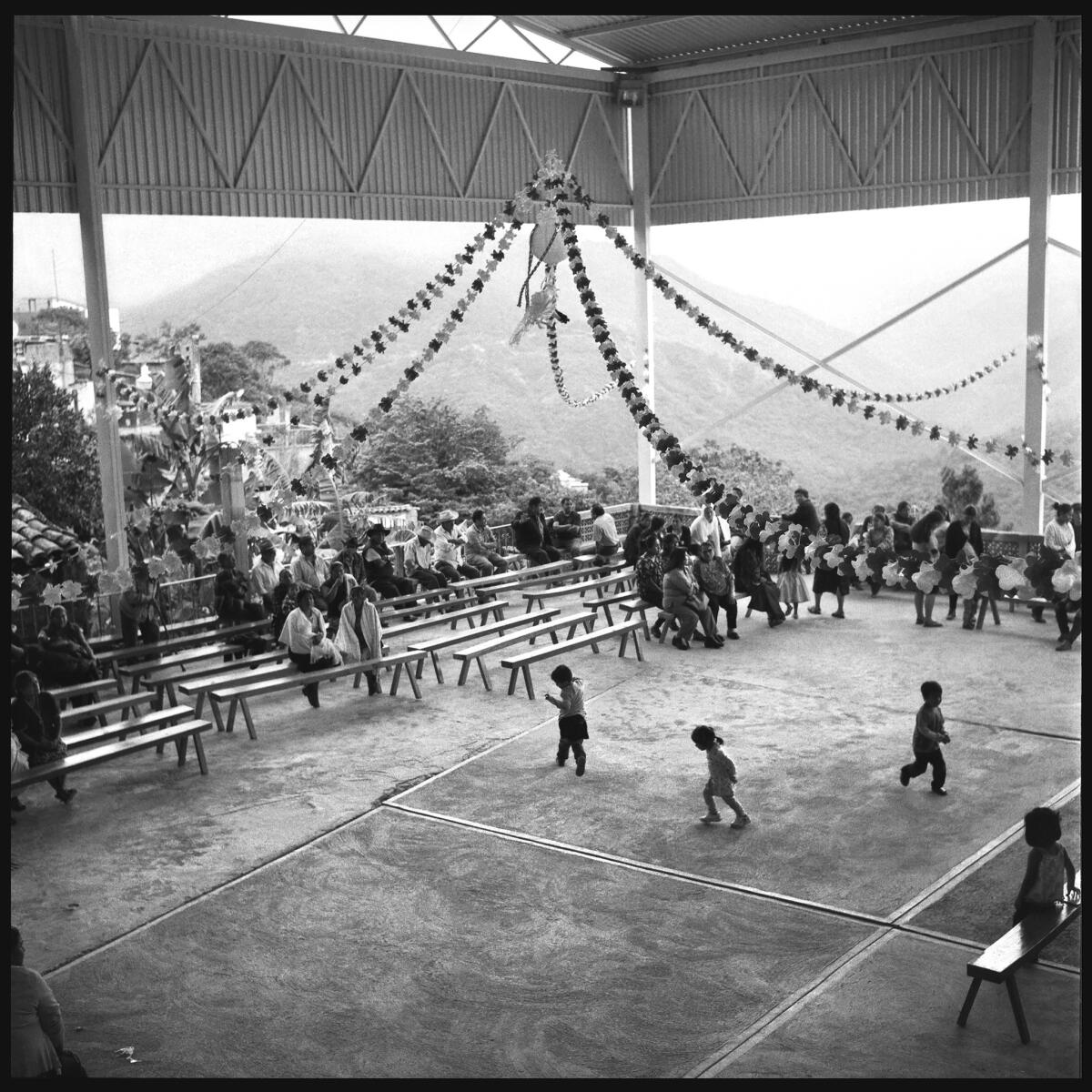

In Los Angeles you can find the biggest community of Oaxacan people outside of Oaxaca. It’s really interesting to see how culture migrates, also. I went to one local celebration of Yalaltec people here, and I was impressed about the amount of people that attend to this. And I was more impressed when some of them tell me, oh, this is not as big as it used to be!

It’s interesting how the culture endures, and they keep passing it from generation to generation. You can see three generations of Yalaltec Americans here. Because [many] are Americans, they can travel, and some of them — most of them — I met in Yalalag last year.

People in this country might look at those who come here from Mexico as a single culture. What's distinctive about Oaxacan culture in Los Angeles?

I think Oaxacan culture is one of the most proud of their origins. They keep their music, their food, and they keep them every day. They've tried to re-create all this wherever they go.

It’s interesting how you re-create not just the traditions but the community itself. We have a word called tequio. That means that everyone in the community has to work for the community. So public works are made by the people; there is no one who receives a payment for doing that. It’s something that everyone does at some point in their lives.

Why did you want to photograph this community?

Because I'm from the community. My grandparents and my parents are from this community. Even when I was raised in Oaxaca City, I was surrounded by my culture there, my Yalalta culture.

Oaxaca is one of the states with more diversity, culturally speaking; there are 514 different towns with different cultures. The Zapotec, where I’m from, is one of them. But there are Triquis, Mixtecos, Chamulas — so many different groups.

This [photographic] work is for us, more than for the outside world. Because at the end, it is a way to reconnect us. We know the people in the images. Someone tells me, “Oh, this is my uncle Fidel, and I don’t see him in, I don’t know, 10 years.” Or, “this is my cousin.” I like the idea to create a dialogue over the images.

And what did you get here?

I went to the celebration of San Antonio de Padua — that’s one of the main saints from the village.

St. Anthony of Padua, an Italian saint.

I know! That's why I love all about culture. Every culture takes from everywhere; it’s transformed and evolves. So when someone asked me about some image that maybe is not precisely pure indigenous — everyone takes from everywhere.

What aspects of American life have you seen the Oaxacan community here adapt to?

As an example, [at one event] they were selling traditional food from Oaxaca. Also they were selling burgers. To me that was something funny.

One thing that caught a lot of my attention was a couple of years ago. Yalaltlan people here organized a dansa, a traditional dance. They call it chusca — that means “fun dance,” something that is making a joke. It was interesting to see this chusca dance representing superheroes — and they were dancing to the traditional music from home!

I saw it because someone did a transmission on Facebook, and nowadays we can feel a little more connection with people that's really far away from us, because of social media.

My idea is to complete this project documenting the Yalalta diaspora around Mexico and the U.S. As I say, for me, this is a family reunion.

Your father runs a photo lab, so you’ve been seeing people taking pictures from the time you were old enough to know they were photographs.

When I was young and growing up in Oaxaca, Oaxacan families went to the photo store to develop their memories. Now that’s changed, because people don’t print [pictures] as they used to.

They don't print the photos — they keep them all in their phones.

Exactly. And they lose them sometimes in the phones!

Right now images look so good sometimes that you don’t care about them, like you put a lot of filters in them and you sometimes didn’t even recognize the people.

I think the reason I’m still doing an analog process is because I believe the image needs a support, a physical support. I honestly don’t trust that much on digital. I feel like sometime I could lose my hard drive or, I don’t know, the Cloud can collapse!

I always say that I have a romantic relationship with photography because it’s like, I need the body, I need to know that it’s there and exists in some way.

You shoot always, or often, in black and white, and with an old 5-by-7 large-format camera.

My personal projects I shoot on film and wet-plate collodion. Wet-plate collodion is that process from the 19th century, and it's made on plates of glass or tin. When you get an image, it is a unique photo. It’s not like a negative on film, that you can reproduce. The plate is going to be the only one. And more than that, I think the relationship that you are able to build with the sitter is completely different.

That’s expensive and time-consuming, so you want to get the one photo right, as opposed to a digital camera phone where you can take one per second.

I honestly don’t think I expend as much [time] as if I would do it digitally, because digital you need to have the best camera, and the best camera costs thousands sometimes. And you need to improve your computer, because your computer can’t be the one from three years ago. You need also a faster one to process big files, right?

Do you think you help people to see things differently because you take photos in black and white?

Taking photos in black and white helps me to get focused on the subject and not get distracted by other elements. Mexican culture has so many colors itself. Sometimes color is really distracting. I like to take more care about the shapes and the person in the images than other elements that could be distracting.

How did you get this very old-fashioned camera, and isn’t it hard carrying it around and explaining it to people?

Oh, yeah, always at the airport it’s a nightmare!

I got this camera from when I was living in Mexico City. I have a really good friend who’s also a photographer. He says, “Oh, you need to buy this one,” because, I remember, it was ridiculously cheap at that time; everyone was trying to sell their film equipment.

At the celebration I went to [here], some people started to ask me about the images, if I do a lot of Photoshop, or how I do this type of images. Because they looked surreal to them — especially the project of “Mestiza,” the images in the series.

They didn't understand the process of this images. I was telling them, well, this is an interpretation. Always in photography, you need to see it like that. Especially nowadays; everything could be just fake. The wet-plate, you cannot erase any wrinkle. You cannot burn or lighten anything from the plates, because the plates are un-manipulable.

What reaction did you get here as you were photographing people?

When I shoot on the Rolleiflex, I think for the large format [camera], you impose yourself, because obviously the equipment is so big, you cannot carry the camera just with your hand.

It’s an entire circus to do the wet plates. But the Rolleiflex gives me some kind of privacy; I call the attention of the people because the camera is old and looks strange, and I'm not looking on the viewer — I'm looking on the glass. I’m always looking down. I’m not looking in front. In some kind of way, that lets me hide a little.

I also like the idea of saying, OK, we need to wait to develop the film. Then you're going to see that image. We just get used to seeing the image there in the same moment as we took it, and erase it if I don’t like it — I’m just gonna delete it, right?

Right now we’re in the 500th anniversary of the Spanish conquering Mexico. And your images seem so striking because they are evocative of indigenous people.

We are living in a new wave of documentary projects, especially about native cultures. And I think of these as a result of an attempt to decolonize the idea of how we represent ourselves and how we see ourselves in the world.

I like the idea precisely to show how the culture migrates and moves, and that is not something just specific from my culture.

I believe in the possibilities that we have to show these other cultures in the world. We are going to see the things that we share with them, even when we don't dance in the same way or even if we don’t eat the same food.

And I think that could give us a better idea of how diverse the world is, and how we are part of that diverse world. I’ve been thinking more about all these decolonization processes and that individual that maybe we’ve been trying to erase in the last hundred years. And now we are in these lucky times when we can try to honor and give the cultures in the world their place.

As I say, we have been trying to get homogenized in some kind of way, and we forget about the relevance that each culture has in the world.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

MORE PATT MORRISON ASKS

Guess what? The rich really are different from everyone else — and it ain’t pretty

Have tech companies like Facebook tricked us into abandoning our humanity?

Ken Burns on making his Vietnam War documentary: 'I was humiliated by what I didn't know'

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.