In Shanghai, a Jehovah’s Witness finds freedom — and space to question her beliefs

- Share via

A lot of people seem to know when their life needs to change. Author Cheryl Strayed went on a hike expressly to “change her life.” I was waiting for things to change, sure. But I had been raised as a Jehovah’s Witness — change had nothing to do with me. That was God’s department. My role was to preach about the end of the world, Armageddon, which I knew was imminent, and to wait for the paradise on Earth that God promised would follow.

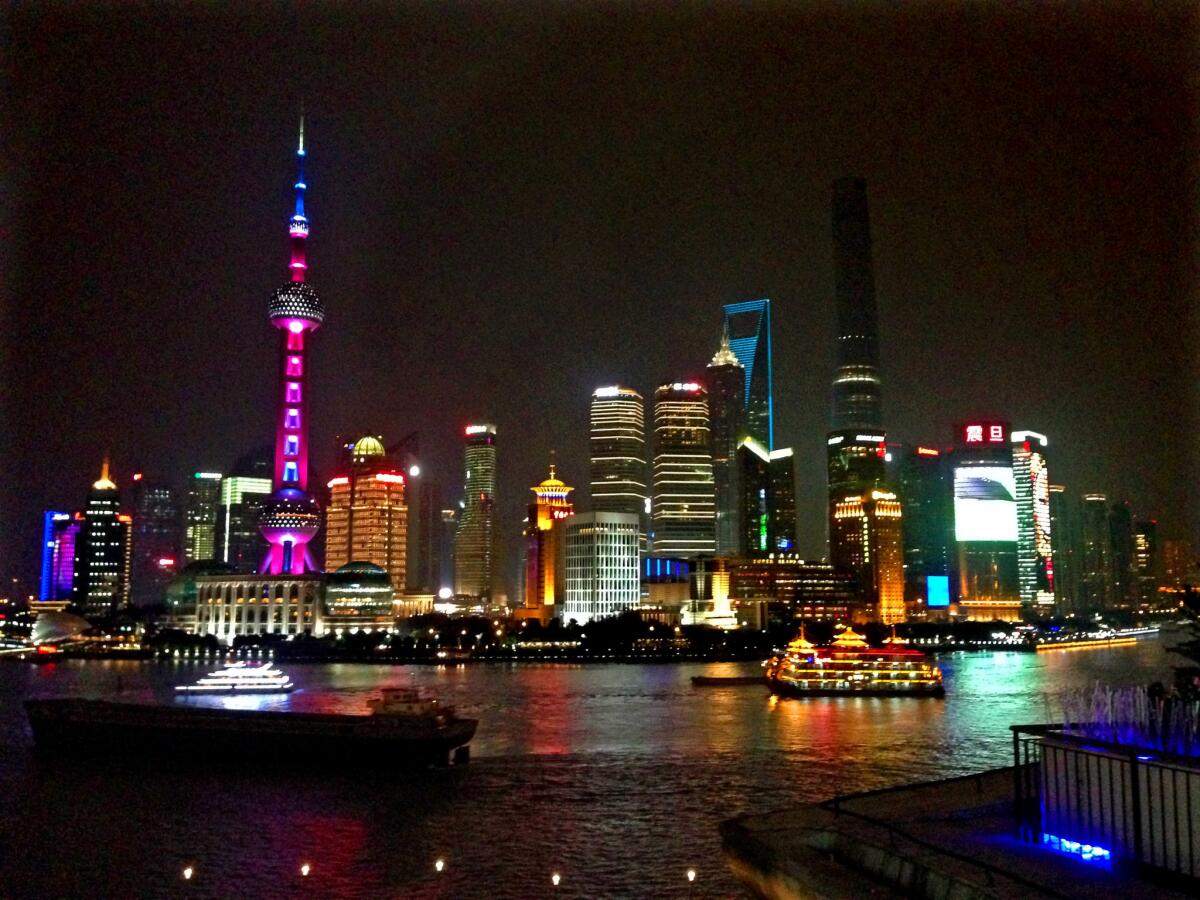

Of course, only God knew when the apocalypse would come, so it helped to keep busy in the meantime. I had figured a good way to pass the time until Armageddon would be to learn Mandarin and go to China to preach. With this in mind, my husband and I — married at 22 — moved to Shanghai. Our relationship was not good, but our religion forbade divorce, so we distracted ourselves by learning Chinese, preaching 70 hours a month and finding potential converts.

In China, most religions are banned, and our preaching was illegal. When I wasn’t working part time at a podcast company that teaches Mandarin, I was out in the city, a secret missionary. I used a fake name. At times, I was followed. My cellphone was monitored. Emails were blocked.

But in spite of this seeming control and constriction, for the first time in my life I had some freedom. Unlike at home, there were no meetings three times a week, no meet-ups every morning for preaching. There were no rules against getting close to “worldly” people. To preach, you first made friends, and when you were fairly certain the person wouldn’t turn you in, you slipped the Bible in.

This new way of living was disorienting, and on top of that I was speaking Mandarin, a language so different I almost had to change the way I thought in order to speak it. As I taught my potential recruits about the end of the world, it was as if I heard what I was saying for the first time, in this new tongue.

And some of what I was saying began to sound odd to me.

When my students told me about their ancient culture, it made me feel arrogant. Here I was, a white person, instructing them to trade in their thousands of years of cultural wisdom in favor of my 120-year-old American religion. Cracks in my faith began to form.

One day at work, a customer named Jonathan emailed me after his first online Chinese lesson. He linked to a video that showed a man being hit by a bus, then crawling out from under it alive — a metaphor for learning Chinese. I could relate. Since it was my job to reply to the students, I wrote back. Jonathan responded immediately. He told me he lived in Los Angeles and had flunked out of Mandarin in college, but that my company’s podcast had rekindled his interest.

Corresponding with a worldly person was a dangerous line to walk for a Jehovah’s Witness. I was married, and a Witness woman was not supposed to be overly friendly with a man who wasn’t her husband, let alone not a Witness. But there were so many barriers between Jonathan and me — a computer screen, the great firewall of China, an ocean, even — that it seemed a safe enough distance to write back once, twice, 10 times, then answer the Gchat that popped up one morning.

We spoke a lot about learning Chinese and life in China. But my religion was 90% of my world, so it was inevitable that the conversation turned toward spirituality. In vague terms, of course. As the Witnesses in China told me when we arrived, the government had 2 million people monitoring the internet.

When I started to tell Jonathan my beliefs, he stopped me. “Wait. What religion are you part of?” he asked. When I told him, he said, “I knew you were under the control of something.”

I was taken aback. And mad. He was forceful and didn’t care about tact. But I was just as sure of myself. My beliefs were between me and God, and none of his business, I insisted. This was the beginning of an argument that, in between our other conversations, continued for months.

Jonathan began to educate himself about my religion. He looked up information about mind control. He read articles by psychology experts and a book by a former Witness leader. He watched videos made by people who had escaped indoctrination.

Because we were forbidden from reading anything critical of our religion, I was afraid of what Jonathan might tell me. But I started listening.

After a year of this, I had begun to see that some things in my religion were simply untrue. Yet I had built my whole life around these beliefs. Without them, who was I? If I renounced my religion, I would be shunned by everyone, including my family and friends. I had been a Witness my whole life. I didn’t know how to live without it.

Jonathan and I met. I had a stopover in L.A., and he picked me up at the airport. When I said hello I felt as if I was being pulled by some force. I did not expect to be attracted to him. I knew that the internet distorted perceptions and everything would be different in real life. But it wasn’t.

I made the decision to commit adultery without really making it. A kind of robotic force propelled me to do it; not desire, not lust, nothing purposeful. It was more a passive action. I needed a way to bring about my own apocalypse, because that was the only ending I understood. In my religion, there was no other way out.

Years later, shunned by my family and friends, I became interested in understanding how something that was so obviously false had so fully controlled me, a reasonably intelligent human being. Had I been in a cult? Was mind control the reason I stayed so long? I scoured all the research I could find.

One night, I found this: “Although some people do … think their way out of the [cult], it is much more likely that an alternate, escape hatch attachment relationship is the key to breaking free.” Such a relationship, it said, brings resolution and a new way of thinking.

Even though I am no longer religious and do not feel bound by rules from an ancient book, I still feel shame at times for ending my marriage the way I did. My husband had admitted he didn’t love me, but I still felt bad for hurting him by burning everything down.

Now I understood: The great irony was that I had needed to. I had to commit this biblical sin in order to find my God-given freedom.

To get out, I had to let someone in.

Amber Scorah is author of the memoir “Leaving the Witness: Exiting a Religion and Finding a Life.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.