Haunting photos from Kent State made me wonder: Where were the black students?

- Share via

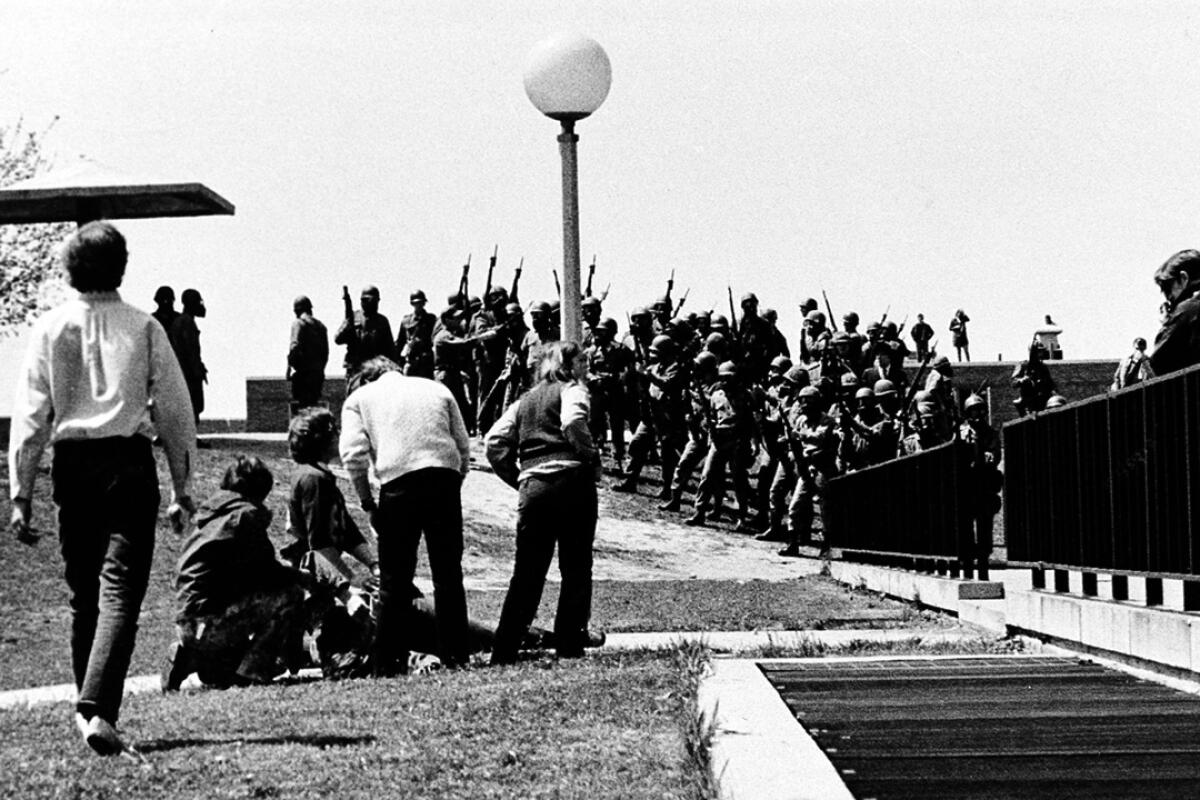

The images from that day are horrific: National Guard troops, armed with rifles and bayonets, advancing across the campus lawn; an anguished teenage girl kneeling beside a young man on the pavement as he bleeds to death; a clutch of students gathered on a grassy hill, comforting a classmate who’s taken a bullet in the chest.

The reality was even worse: Four students were killed and nine wounded by National Guardsmen who fired without warning into a crowd of unarmed students protesting the escalation of the Vietnam War on the campus of Kent State University in Ohio.

Monday is the 50th anniversary of that American tragedy. And the photos taken that day offer a sobering glimpse of a nation at war with itself — a nation not so different from the one we live in today, steeped in conflict and struggling to manage fractious ideological, social, racial and generational splits.

Ohio’s hard-line governor — who’d summoned the National Guard — used the deaths to shore up political support in an election year. He called campus protesters the “worst type of people America harbors … worse than the Brownshirts and the Communist element and also the Night Riders and the vigilantes.”

In a Gallup Poll taken days after the shootings, 58% of respondents blamed the students for the bloodshed and only 11% blamed the National Guard.

But college students across the country saw things very differently. The carnage sparked a national student strike, which mobilized more than a million young people and forced the shutdown of hundreds of universities.

I was a sophomore then at an all-black Cleveland high school, a 40-minute drive from the Kent State campus. Like many of my classmates, I would be the first in my family to attend college, and Kent had seemed like a good fit — far enough away that I could live in a dorm, but close enough that I could bring my laundry home.

But those images — of students fleeing tear gas and bullets, and huddling over the dead bodies of friends — would haunt me for years and knock Kent off my college list. And the photos made me wonder about something else. Where were the black students?

I can still remember, after the shock subsided, my non-college-going friends began teasing me: If those troops could shoot white kids so nonchalantly, why do you think you would be safe?

And as the anniversary of the tragedy rolled around again, I decided it was time for answers to a question I’ve carried around for half a century: What did it feel like to be in the eye of the storm back then, when there were so many things that needed protesting?

I was talking about that with my sister-in-law, and she mentioned that her uncle had been president of the Black United Students on campus at the time of the massacre. Last week, I talked with him.

“It was not some sort of extreme place,” said Charles Eberhardt, a retired Cleveland math teacher who earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Kent State. “There were all types of peace initiatives and nonviolence campaigns.”

It was the presence of the National Guard, he said, that shifted the tenor of antiwar rallies that spring.

Eberhardt, now 70, explained that members of his group were allied with the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which organized antiwar protests on campuses across the country.

“We supported their issues, including ending the Vietnam War,” Eberhardt said. “And they supported ours.”

But on May 4, 1970, race presented an unexpected dividing line.

The rally that day followed a weekend of unruly rallies that had drawn thousands of students outside to protest President Nixon’s decision to invade Cambodia, prolonging an unpopular war he’d promised to end.

When the ROTC building on campus was torched, to the cheers of exuberant activists, troops from the Ohio National Guard were dispatched to quell the protests and protect the smoldering husk.

When Eberhardt saw hundreds of helmeted troops carrying rifles and bayonets, positioned around the campus, he sensed this was a battle the students wouldn’t win.

He’d been a teenager in Cleveland when race riots swept the city four years earlier. “I knew this would be a bad scene,” he said, remembering heavily armed Guardsmen patrolling street corners and rolling down his block in military tanks. “You don’t forget how that made you feel.”

The Black United Students had planned to join the peaceful protest scheduled for noon on Monday, May 4. Instead, Eberhardt spent the morning urging black students to remain in their dorms “and avoid any contact with the Guard.”

“To be honest, we didn’t think they would shoot or kill anybody on campus,” he says now. “But we didn’t want to have anything to do with them.”

So while white students were defiantly protesting on the Commons, never imagining they could be shot, black students were uneasily sheltering indoors because they imagined they’d be easy targets.

“A lot of us wanted to be out there,” he said. “Most of the students on campus were antiwar.”

Eberhardt was in his room when he heard the volley of gunshots; he dashed across campus and into the melee, where he got the news that several students had been hit. “I was stunned, just totally shocked,” he said.

“I couldn’t believe they were shooting, with live ammunition, on a college campus. I couldn’t believe they would do that against white students.

“I was shocked, totally shocked. And overcome with sadness for a long, long time,” he said. “For the kids who died, for their parents, for all of us.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.