Mustering up gratitude in a pandemic Thanksgiving

- Share via

As I was making my weekly grocery deliveries to my mother and my in-laws in El Monte last week, I spotted a line of more than 25 cars stopping traffic at Santa Anita Avenue. They were waiting to enter the parking lot of the food pantry there. The patiently inching cars, wrapped around the block, were another reminder that this Thanksgiving is unlike anything any of us has ever seen.

As in so many other places, the mood around town seems subdued by pandemic stresses. The only remotely festive street decorations are the banners from the spring that celebrate 2020’s college graduates. Some of the city’s recent online posts seem falsely cheery — announcements for the Turkey Trot Marathon and a Thanksgiving Tablescaping Challenge that I can’t imagine anyone around here doing.

Gratitude is difficult to muster this year, when El Monte stands among the cities in Los Angeles County with the highest COVID-19 rates. El Monte now has a case rate of more than 570 per 100,000 residents. In this way, our city resembles Pomona and La Puente and Downey and Maywood and numerous others. Naming these places feels like naming family, because their Latinx communities make up so much of the county’s frontline and essential workers. This vulnerable population accounts for 40% of reported coronavirus infections and 51% of COVID-19 deaths in the county.

At the start of the pandemic, I entered the jobs of everyone in our family on a COVID-19 exposure-risk chart and found that my wife, a social worker in a county hospital, had the highest position on the grid, her red dot alongside the one for paramedics. We paused our 4-year-old son’s daily childcare routine with his abuelitos both to lessen their risk and to reduce ours, since my wife’s mother works as a picker in a warehouse where the virus claimed a temporary worker in Building E, a death that has remained a shadowy catalyst in our worries.

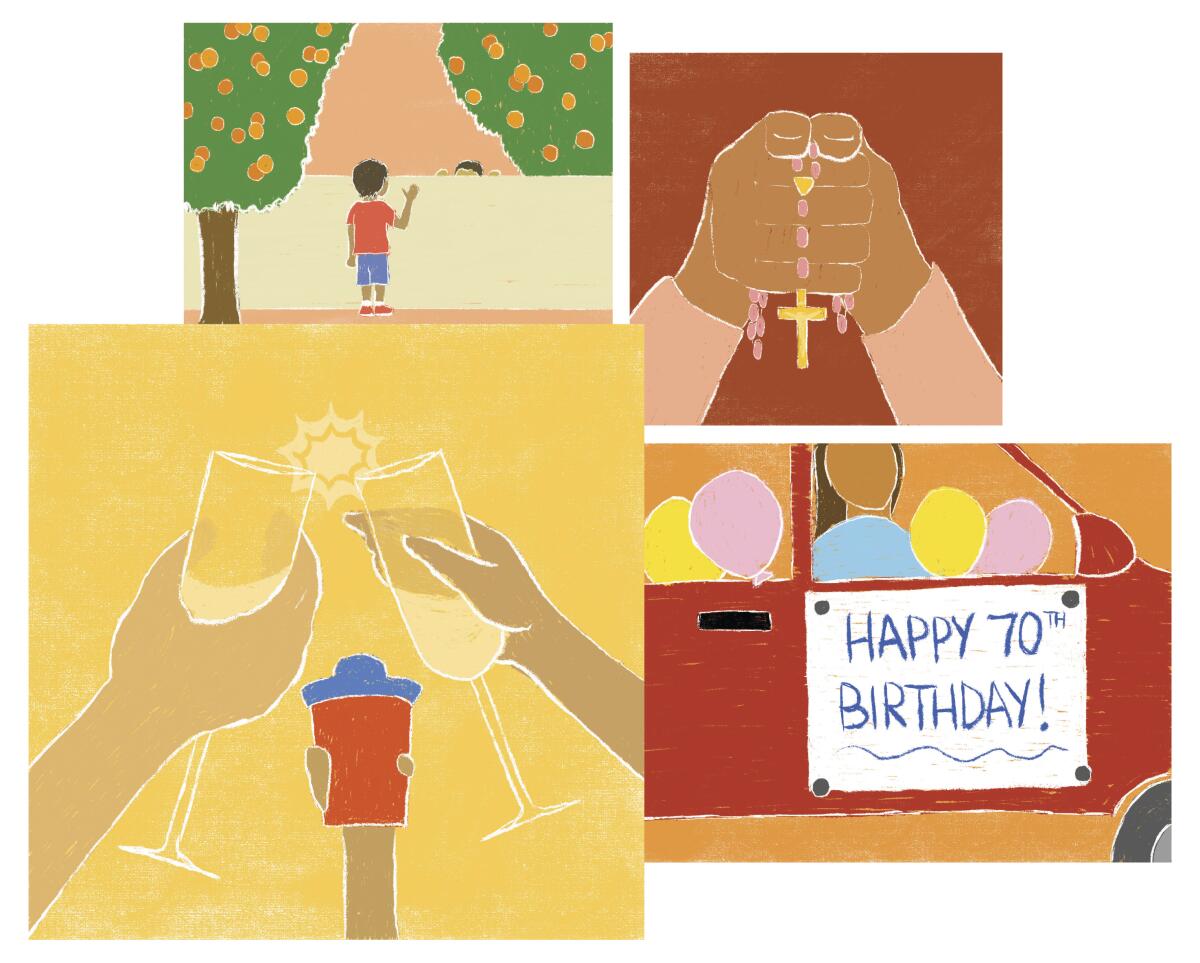

That anxiety has been a constant since the spring. One April night, our bathroom reeked so intensely of rubbing alcohol that I thought our bottle had spilled under the sink. I soon realized the odor was coming from next door. Our neighbor was wiping down every interior surface in his family’s cars because his wife had tested positive for the coronavirus. For her, that was the beginning of an 81-day ordeal that would span three hospitals, three weeks in the ICU, two weeks of residential physical therapy and countless Zoom rosary sessions. When she finally came home in July, everyone felt it was a genuine miracle.

This year was supposed to be the year my son finally got to play T-ball (“Go T-Ball Dodgers!”), the year we took him to Legoland, the year that he and a 4-year-old neighbor would become good friends. Instead, the boys continue saying hello by peeking over the wall that separates them. My son’s 2020 has been full of disappointments.

It has also been the year that my wife and I became drive-by party experts. The year that she developed admirable sign-lettering skills and I figured out that the best way to attach Happy 75th Birthday!!!/Happy Graduation!!!/Happy 70th Birthday!!!/Happy Beyoncé Birthday!!!/Happy Lisa Simpson Birthday!!! signs to our car is to use magnets, not packing tape. At each celebration, my relatives and I do a chócala with our elbows and say that we intend to stay alive so we can party for real when this is all over. But 2020 has also been the year when my wife and I confront the fact that staying alive may not be up to us.

And so we have chosen to find delight in the daily moments with our son. Delight at his index finger tapping on my arm as he sits beside me and stares at math homework on his computer screen, delight when he lines his stuffed animals across our couch so they can watch his cumbiatón dance moves. Delight as I spin him around in my arms the way my father once did with me, delight even when consoling him as he cries at crucial Dodger victories because the neighborhood’s celebratory fireworks still scare him.

If this year has any silver lining, it has been getting to be so present for the incremental developments in our child’s life. For months now, at dinner each night, we have toasted being together, the three of us, the clinking of our glasses a true act of thanksgiving, a conscious appreciation that we have gotten another day. Because he’s only 4, I don’t know what our son will remember of this time. I hope to recall as much of it as I can.

Michael Jaime-Becerra is an associate professor of creative writing at UC Riverside and author of “Every Night Is Ladies’ Night.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.