Pay back the Bruces for Bruce’s beach

- Share via

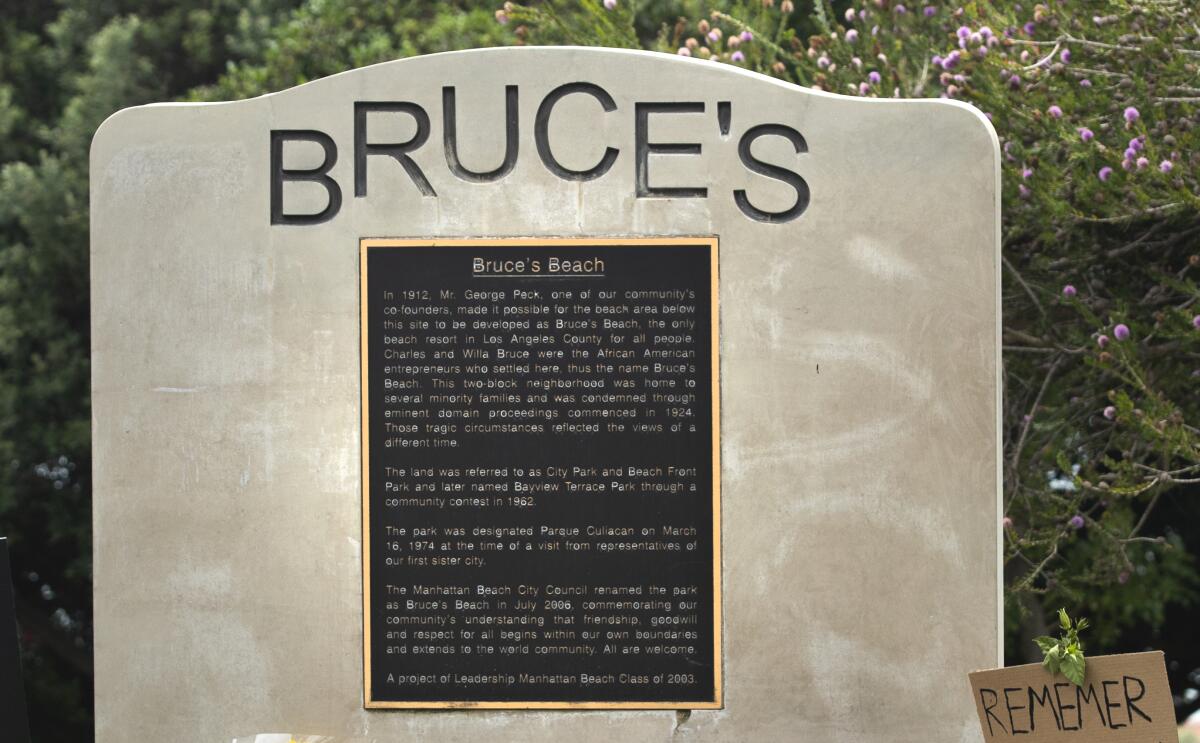

The last straw for the leaders of Manhattan Beach in the 1920s may have been the big party thrown at Bruce’s Beach, a Black-owned sliver of property extending down to the shore and one of only two patches of beachfront open at the time to Los Angeles County’s African American residents. Alarmed at the number of Black partygoers and worried that their presence could be a portent of things to come, the South Bay city’s board of trustees condemned the land to turn it into a public park. The Bruce family was bought out, along with adjacent property owners, keeping the wealthy city mostly white up until the present day.

Now Manhattan Beach is being roiled by a debate over how to make amends for the city’s early 20th century racism — and whether amends are even called for, and whether racism was really at play, as opposed to a commendable civic drive to make all beachfront equally accessible to all.

Of course amends are called for. And of course it was racism. The surviving Bruces should be compensated for their family’s loss, which most certainly wasn’t covered by the small payment the family received. The city also owes the public a greater acknowledgment than it has yet made that it grew and prospered on a legacy of racist exclusion. And it owes the Bruces an apology.

The racism at the heart of the forced sale of the Bruce property and the closing of the shore to Black beachgoers followed a pattern of emerging Southern California Jim Crow segregation that would have been at home in the Deep South. L.A. city officials, for example, segregated the city’s public swimming pools in 1925. Meanwhile, Black people who wanted to go to the beach had only two options: the “Ink Well” in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica, and Bruce’s Beach, bought by Willa Bruce in 1912.

As told by historian Douglas Flamming in his book “Bound for Freedom: Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow America,” the new “public” beach that replaced Bruce’s Beach was leased to a private operator, Oscar Bassonette, for a dollar a year — and Bassonette granted access only to whites. That cannot have come as a surprise to Manhattan Beach’s leaders.

A Black college student tested the restriction and police ordered her to leave. She refused and was thrown into jail in her swimsuit.

After a swim-in organized by the NAACP resulted in more arrests, Manhattan Beach agreed to open the beach to all, at least formally. The Los Angeles Times editorialized that the move would keep the shore “free from private exploitation or the erection of barriers.”

So that was it, right? Injustice corrected? Hardly. Black beachgoers were made unwelcome and felt unsafe. Restrictive covenants kept Black buyers from purchasing beach-adjacent properties in the South Bay, mirroring one of the tactics used to close down the Ink Well a few miles up the coast.

The land that was the Bruces’ is now owned by Los Angeles County, and county Supervisor Janice Hahn is considering several options for fixing the historical wrong. The passage of time makes each option somewhat thorny. For starters, it’s hard to argue for cutting off public access to the beach, even if it’s in the name of restoring rightful ownership of the adjacent land. But the fact that the situation is complex is a poor argument for not compensating the family for its loss.

Some who oppose any apology or recompense argue that racism could not have been a factor because Manhattan Beach condemned adjacent white-owned land as well as the Bruces’ and other Black owners’ property. The pattern of racist practices at the time — the segregation of pools in neighboring L.A., the racial restriction under Bassonette, the private covenants barring sales to Black owners — puts the forced sale in its proper context. Of course its purpose was to eliminate the Black presence.

And why should modern-day Manhattan Beach residents apologize for and shoulder the burden of acts by their predecessors nearly a century in the past? Because they, like all of us, benefit from privileges we sometimes see as a birthright when they are in fact the inheritance we gain from historical wrongs. An apology is an acknowledgment of that truth, and monetary reparation is a partial payback for unjust gains and losses.

The question gets even harder when applied to thefts and cruelties inflicted further back in history. What, for example, can repay the dispossession and genocide of Indigenous people and the forced labor of Black slaves? But the difficulty of such questions is no reason to slow justice in this case, in which the injustice occurred in living memory and close descendants continue to claim their family’s legacy. Should it be the county that repays the Bruces, or the state, or Manhattan Beach? All worthy questions. But begin with the apology.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.