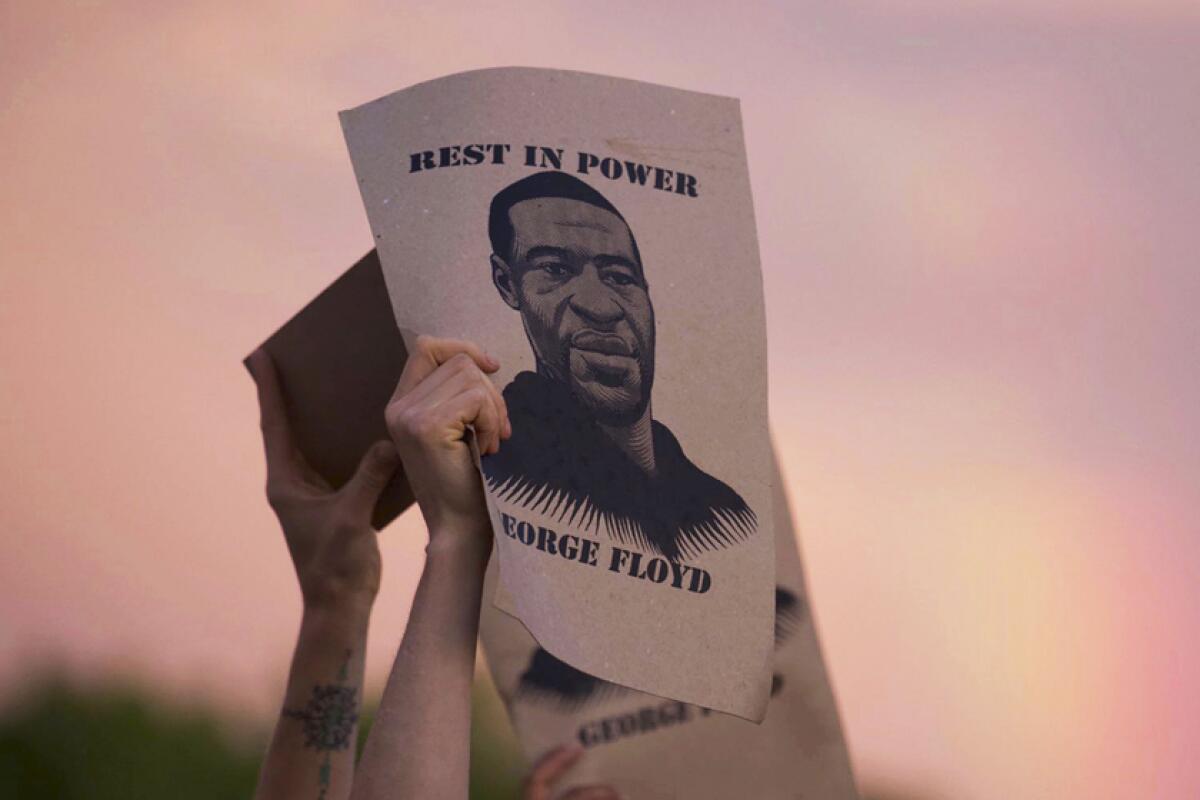

One year after George Floyd’s murder, has the ‘reckoning’ begun?

- Share via

It was a frightened and weary nation that headed into Memorial Day weekend 2020, having been drained by a divisive impeachment trial, shocked by Kobe Bryant’s death and traumatized by a worldwide pandemic unlike any calamity in living memory. Americans had grown tired of waiting in line for groceries, hoarding toilet paper, arguing over which workers are or are not “essential,” managing schoolchildren without schools, missing baseball, basketball, restaurants, amusement parks, movies and malls, being shut in and locked down (or, at great risk to themselves, serving those who were shut in and locked down). They were advised to spend the summer’s annual three-day launch party at home, but many were having none of it and saw the long weekend as a chance to finally put the crazy first part of the year in the rearview mirror.

The days were long and getting longer, and in northern parts of the country such as Minneapolis, it remained light well into the evenings. The sun was still in the sky shortly before 8 p.m. on May 25, Memorial Day, when George Floyd bought a pack of cigarettes at Cup Foods in the Powderhorn Park neighborhood, and a young store clerk who believed Floyd had used a fake $20 bill called 911. The sun was still up at 8:08 p.m. when Minneapolis Police Officers J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane approached Floyd in his SUV, at 8:17 p.m. when Officers Derek Chauvin and Tou Thao arrived, a few minutes later when Chauvin began to kneel on Floyd’s neck, and through the next nine minutes and 29 seconds, as Floyd pleaded that he couldn’t breathe, called in agony for his mother, said he was dying and finally went limp and silent. The evening sunlight illuminated the images caught by 17-year-old Darnella Frazier on her cellphone and by the officers on their body-worn cameras.

Many police leaders and criminal prosecutors — officials who are generally quick to condemn atrocities by civilians yet insistent on reserving judgment when the assailant is a law enforcement officer — were shocked and quick to label Chauvin’s killing “murder.” Meanwhile, those of us in the sometimes excessively cautious news media described the same killing in self-consciously awkward and noncommittal terms, writing for example that Floyd “died under the knee” of a police officer. Only after the jury said it was murder, nearly a year later, did the news consistently affirm the grisly reality we had all seen.

The Times Editorial Board examines the reckoning of the last year and considers what it means for policing and protest in Los Angeles and elsewhere.

Reporters, editors and commentators also searched for a term to sum up the protests, the violence, the recriminations, the racial inequities, the questioning of police powers, the wider-than-ever use of words such as “structural” and “institutional” racism. We called it “a national conversation” about race, and indeed there were conversations of a depth and breadth and intensity not heard here in quite some time, but we’ve been having that conversation in one form or another through the entire life of our nation, and it was renewed in this generation even before the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and Eric Garner and Michael Brown in 2014. This time seemed different, perhaps because everything in 2020 was different. In headlines, news stories, columns and editorials we called it a “reckoning,” and used the word so often with insufficient examination that it became a cliche.

But it just might be the correct term after all. A reckoning is an acknowledgment of a debt owed and still unpaid. It calls to mind the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s accusation delivered nearly 60 years ago at the Lincoln Memorial that the nation refused to pay when Black people tried to cash the metaphorical check written by the founders in language promising that all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with unalienable rights.

“It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned,” King said.

It is a reminder of the compensation for forced labor — “40 acres and a mule” — that was promised to freed slaves but quickly revoked.

It is a reminder of the comparative puniness of the alleged forgery that led to Floyd’s murder.

In a series of editorials this week, we will examine the reckoning of the last year, consider what it means for policing and protest in Los Angeles and elsewhere, and note that this time around Memorial Day happens to fall on the 100th anniversary of the violent, racist eradication of “Black Wall Street” in Tulsa, Okla. The chains that link Tulsa and Minneapolis, Los Angeles and Ferguson, Mo., 2021, 1865, 1776 and 1619 are still unbroken and the debt still unpaid. The interest is accumulating.

This is the first in a series of editorials.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.