The Democrats’ far-reaching budget bill: An antidote to the filibuster?

- Share via

Senate Democrats unveiled the outlines of a bill this week that would implement the bulk of President Biden’s domestic agenda, assuming they can keep their party united behind the details still to come. And though progressives may be disappointed that it did not go further, the measure could deliver the largest expansion of federal support programs of any single piece of legislation since the 1960s.

Which is not to say that it’s radical. Instead, Biden and his Democratic allies are seeking to build on a wide range of programs that haven’t kept pace with the public’s needs. Even the new elements, such as paid family leave and universal pre-K, mirror existing programs at the state level. And in a sense, they’re just trying to seize an opportunity that previous Democratic presidents were denied by polarized politics and ailing economies.

The fact that they might be able to do so with tenuous Democratic control of the House and Senate illustrates a separate point: If the filibuster isn’t a factor on legislation this important (and expensive), why should it be a factor on any bills?

The proposal comes in two parts: a budget resolution for fiscal year 2022, which starts Oct. 1, and a budget reconciliation bill that turns the resolution’s nonbinding instructions into law.

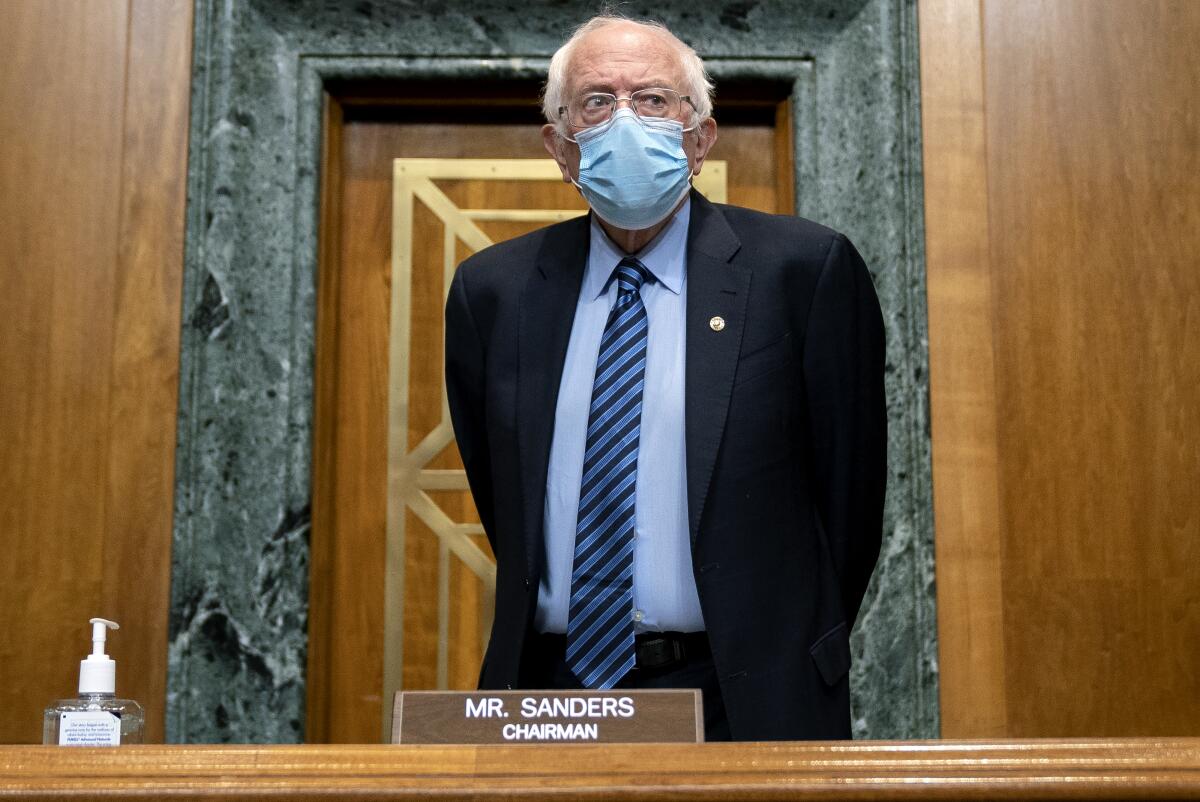

So far, Democrats on the Senate Budget Committee, which is led by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), have agreed only to a set of bullet points about the package: It will call for a whopping $3.5 trillion in additional spending over the coming decade, mainly in social programs and responses to climate change. And it proposes to pay for the new spending with a combination of tax hikes, spending cuts and economic growth.

There is much to like in the outline, particularly the clean energy initiatives and the expansions in tax credits and subsidies for low- and moderate-income workers and families. There are significant provisions that have far too little detail, such as the ones to expand Medicaid in the states (all Republican-controlled) that have declined to do so, to invest in housing and to extend legal permanent residency status to more immigrants. And there are elements that could be good or bad, depending on how the blanks are filled in.

The proposals to raise taxes on high-income individuals and corporations can’t be judged because they’re far too vague at this point. But the Biden administration has persuaded more than 100 countries to agree on a minimum tax level for multinational corporations, so the groundwork has been laid to mitigate the competitive effects of any increase in corporate taxes here.

For all the missing detail, though, there’s no mistaking the senators’ ambition, or that of Biden’s effort to bring federal social programs into line with 21st century realities — and with what other industrialized nations have been doing for years. The magnitude of the package is mainly a reflection of how badly the federal government has neglected many of the commitments it made over the last 60 years.

It’s worth noting that the outline is supported both by Sanders, who’d wanted a $6-trillion bill, and by Sen. Mark R. Warner (D-Va.), one of the least liberal members of the Democratic caucus. And because budget bills aren’t subject to filibusters, Democrats won’t need 60 votes to push the package through the Senate — they can do it with the 50 votes in their caucus, plus Vice President Kamala Harris’ tiebreaker.

Put another way, the single most consequential piece of legislation to come through Congress in years will be decided by a majority vote. So why, again, would it be so destabilizing and destructive to tradition if every piece of legislation could be decided that way, instead of requiring 60 votes to get past the seemingly unavoidable filibuster?

Defenders of the filibuster, including Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin III of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, have argued that policies backed by larger, bipartisan majorities tend to be better and more sustainable. They may be right, but that’s not how Congress has operated for the last decade or more. Incredibly consequential pieces of legislation, such as the 2010 Affordable Care Act and the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, were enacted with the support of just one party, often by exceedingly narrow margins.

Policies change back and forth with elections because elections matter. And so do the opinions of the unelected masses, who aren’t nearly as polarized as the people they’ve sent to Washington. Key details remain to be seen, but the outlines of the Democrats’ budget package reflect the wishes and needs of those masses. So do proposals to guard against voter suppression, overhaul our immigration laws and invest in critical infrastructure. The filibuster shouldn’t be available to use against any of them.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.