Trump’s immunity arguments are laughable, unpersuasive — and dangerous to democracy

- Share via

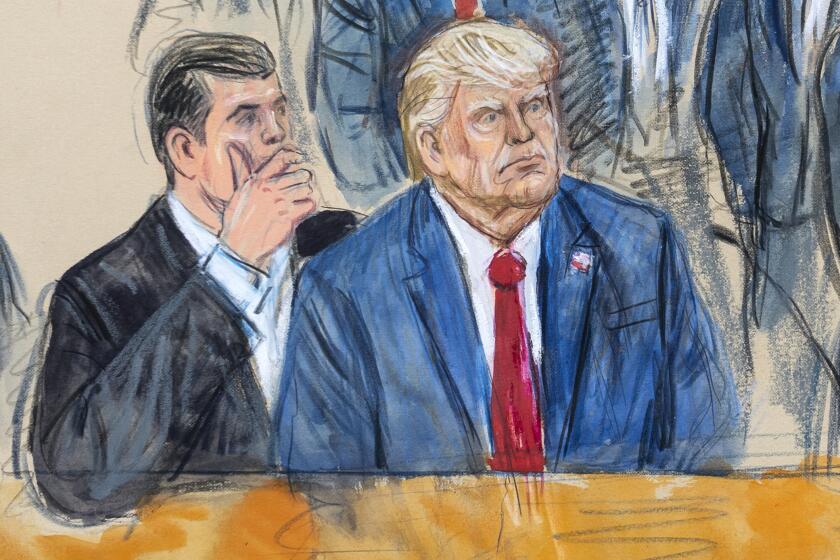

On Tuesday, a federal appeals court in Washington will hear arguments on a question of vital interest to the rule of law: whether former President Trump is immune from prosecution for alleged crimes related to his elaborate efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit must reject Trump’s claim, not only to ensure that he faces a jury but also to deter future presidents from acting criminally — and not just when they try to cling to office after losing an election.

The Supreme Court declined a request from special counsel Jack Smith to rule on this case before the appeals court weighed in. If the appeals court rules in a timely fashion, the high court could still review the immunity issue in time for Trump to be put on trial before the Republican National Convention in July. (On Friday the justices said they would take up another controversy involving Trump, agreeing to review a Colorado Supreme Court decision holding that he was barred from the ballot in that state because he engaged in insurrection.)

Special counsel Jack Smith has the right to ask the Supreme Court to expedite the former president’s case. Time is of the essence because Trump could be the GOP’s 2024 presidential nominee.

In arguing for immunity for Trump, his lawyers suggest that the actions alleged in Trump’s indictment by a federal grand jury — which include efforts to assemble fake electors and press Vice President Mike Pence to reject electoral votes for Joe Biden — fall within the “outer perimeter” of the president’s official responsibility.

The “outer perimeter” language appeared in Nixon vs. Fitzgerald, a 1982 Supreme Court decision holding that former President Nixon couldn’t be sued by a former Air Force analyst who claimed he was fired because of testimony to Congress about cost overruns. The court said that a former president is entitled to “absolute immunity from damages liability predicated on his official acts.” Trump’s lawyers suggest that the Fitzgerald case, which involved a civil lawsuit, means that Trump is also immune to criminal prosecution.

An amicus brief from the group American Oversight argues persuasively that the former president’s immunity claim doesn’t qualify for immediate appeal.

That argument is unpersuasive. First, the actions for which Trump has been charged lie outside even a loose definition of decisions within the “outer perimeter” of the president’s official responsibility. Trump’s lawyers strain to characterize the actions for which was Trump was indicted as “official acts” that “reflect President Trump’s efforts and duties, squarely as chief executive of the United States, to advocate for and defend the integrity of the federal election, in accord with his view that it was tainted by fraud and irregularity.” That characterization is laughable; Trump was acting in his political self-interest, not as a disinterested champion of election integrity.

Second, there is a distinction between civil lawsuits and criminal prosecutions. In a concurring opinion in the Fitzgerald case, Chief Justice Warren Burger stressed that the court wasn’t recognizing “sweeping immunity for a president for all acts.” He emphasized that “immunity is limited to civil damages claims.” In a brief filed with the appeals court, Smith’s office made another important point: The Supreme Court’s concern in the Fitzgerald case about former presidents being subjected to “highly intrusive” lawsuits from “countless people” doesn’t apply in the criminal context.

Thanks to courts, prosecutors and, yes, the voters, the last year saw many of the worst actors in our parlous politics indicted, convicted or ejected from the spotlight.

Finally, Trump’s lawyers point to an “unbroken tradition” of not prosecuting current or former presidents. To which Smith’s office has a pithy reply: Other former presidents haven’t been prosecuted, not because of a tradition of criminal immunity, but because most presidents have done nothing criminal.

The special counsel also notes that “President Ford’s pardon of former President Nixon covering acts during the latter’s presidency rested on the assumption that no post-presidency immunity from criminal prosecution existed.”

Trump’s lawyers are also making the equally unpersuasive claim that Trump can’t be prosecuted because he was impeached and acquitted of inciting an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. That argument depends on a far-fetched interpretation of language in the Constitution saying that an official who has been convicted by the Senate at an impeachment trial can be prosecuted — which doesn’t mean that a president who was acquitted can’t also be criminally charged.

None of Trump’s arguments pass muster legally. But if such expansive concepts of presidential immunity should prevail, they would, as Smith’s office pointed out, protect “a president who accepts a bribe in exchange for directing a lucrative government contract to the payer; a president who instructs the FBI director to plant incriminating evidence on a political enemy; a president who orders the National Guard to murder his most prominent critics; or a president who sells nuclear secrets to a foreign adversary.”

Like his efforts to overturn the 2020 election, Trump’s attempt to have the courts grant him immunity from criminal liability poses a threat to democracy. The appeals court should quickly reject such dangerous theories and the Supreme Court should follow suit.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.