Supreme Court looks ready to protect Maryland’s ‘Peace Cross’ in church-state case

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — The Supreme Court with new Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh faced its first church-state dispute Wednesday, and a clear majority voiced support for keeping in place a nearly century-old cross that honors soldiers who died in World War I.

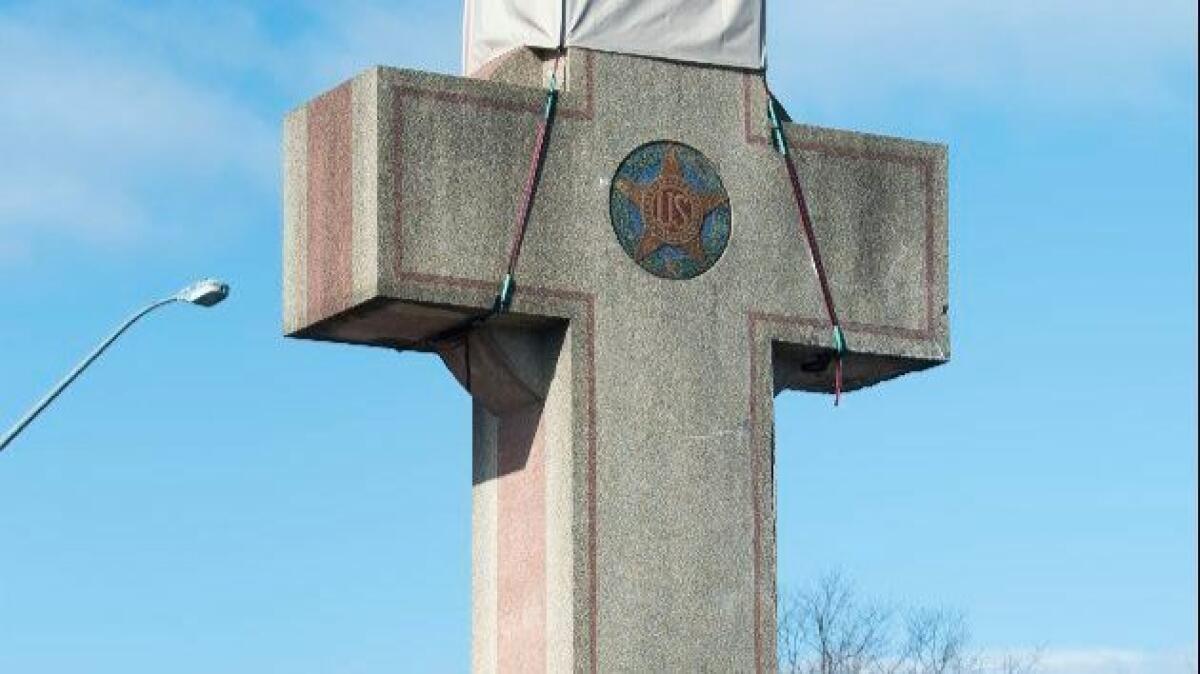

The justices, both liberal and conservative, said the so-called Peace Cross should not be torn down or moved. The 40-foot cross sits in a busy intersection in suburban Maryland.

Justice Elena Kagan said the history of the era showed why the cross should be able to stand. She said the “rows and rows of crosses” near the battlefields of World War I made the cross the “preeminent symbol of how to memorialize” in America those who had died in Europe.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer agreed. “History counts…. We’re not going to have people trying to tear down historical monuments,” he said.

But the past does not justify erecting new memorials with Christian symbols these days, he added. “And so, yes, OK, but no more…. We’re a different country now.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg noted that the United States may have been “overwhelmingly Christian” at its founding, but today it has a broad array of religious faiths.

At the same time, however, the justices struggled with how to devise a legal rule that clarifies when public displays of religion go too far and violate the 1st Amendment’s ban on an “establishment of religion.”

The two new justices — Neil M. Gorsuch and Kavanaugh — said the court’s precedents in this area were vague and confusing.

The justices spent most of Wednesday’s argument posing questions. If war memorials were acceptable for World War I, could a city use a cross to memorialize those who died in Vietnam? If a school suffered a mass shooting, could it erect a cross as a memorial? Or how about a city using a Star of David to honor the victims of a mass shooting at a synagogue or to remember the Holocaust? If religious symbols on public land are forbidden, does that extend to a Native American community?

For the most part, the attorneys avoided giving a clear answer. They said much depends on the context and the reasons for erecting the memorial.

But Deputy Solicitor Gen. Jeffrey Wall, representing the Trump administration, said it would be “quite problematic” for a town today to put up a “naked, unadorned cross” on public property.

He defended the cross in Bladensburg, Md., saying it was “an easy case.” The memorial was erected long ago to honor soldiers, and its engraved words speak of courage, valor and devotion.

While it was apparent which side would win, it was not clear from the oral argument whether the justices would issue a broad ruling that upholds religious symbols on government property or a narrow decision that preserves the Peace Cross in its current location.

Four attorneys argued on Wednesday, and they proposed strikingly different ways to decide the case of American Legion vs. American Humanist Assn.

Washington attorney Neal K. Katyal, representing the Maryland parks commission, said the court should focus narrowly on the Peace Cross. It was erected as a war memorial long ago and should remain where it is. He advised against a “radical change” in the law that would give a green light to religious displays on public land.

Washington attorney Michael Carvin, representing the American Legion, said the court’s conservatives should go broad. Religious symbols are like “religious speech,” he said, and the courts should not limit religious displays, so long as the government is not “preaching conversion.” The legion helped build the cross.

The Trump administration joined in defense of the cross, and Wall argued that religious displays should be generally upheld if they have a nonreligious purpose, such as honoring the war dead or a mass shooting.

Monica L. Miller, counsel for the American Humanists, said the Constitution “at the very least prohibits the government from preferring one religion over another religion.” And she said the court should reject the argument that the 40-foot cross is “essentially a nonreligious, non-Christian symbol that honors everyone, irrespective of their religion.” She said the park commission is “telling Jews, telling Muslims, telling humanists that the cross honors them, when they emphatically say it does not.”

She emphasized her organization was not seeking to have the cross torn down, but instead moved to private land, not public property.

The Peace Cross was built with private funds in the 1920s to honor 49 dead local soldiers, but it has been maintained on public land and with public funds since 1961.

Several residents who belonged to the American Humanist Assn. sued and won a ruling from the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, Va. In a 2-1 decision, the appeals court ruled that because the cross was the core symbol of Christianity, its prominent display on public property was an unconstitutional “endorsement” of religion.

More stories from David G. Savage »

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.