You may soon be asked to take a pay cut to keep working from home

- Share via

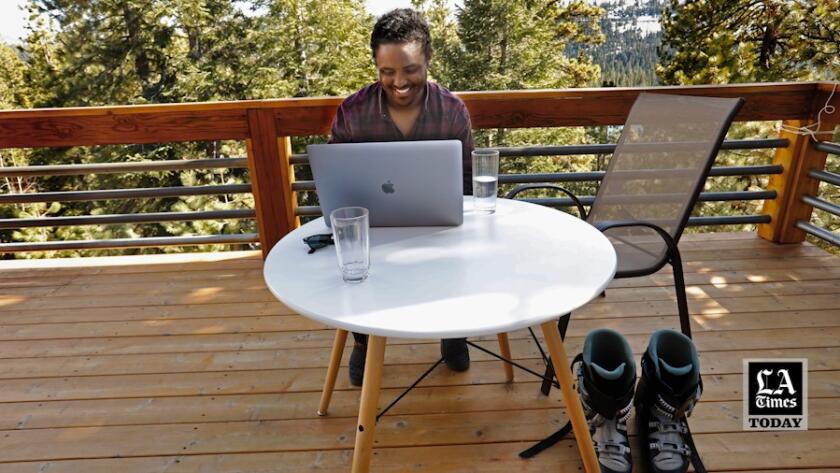

WASHINGTON — Working from home during the pandemic became a surprising success.

Many workers enjoyed a better quality of life plus savings on commuting, office wardrobe and other expenses. Companies boosted productivity and lowered costs.

Now as remote work looks likely to survive in some form for the foreseeable future, a battle is starting to brew over who should pocket those savings, with some employers arguing that working from home is a benefit that should be offset by lower salaries.

With the pandemic easing, more companies are calling workers back to the office. Even so, about 30% of all paid workdays are still being done from home, up from just 5% before the COVID-19 outbreak, according to the Working From Home Research Project led by economists at Stanford and the University of Chicago.

Paying remote workers less is a practice that is already catching on abroad. In Britain, the law firm Stephenson Harwood recently announced that employees could work full time from home on the condition that they take a 20% pay cut.

Right now, such arrangements seem rare in the U.S., probably because of the tight labor market. But that could change in the event of a recession as employers eye how remote working can lower labor costs and boost the bottom line.

The Working From Home project found that 4 in 10 employers planned to use remote work as a way to ease overall wage-growth pressures — though not necessarily by slashing salaries of existing employees. Companies, for example, can fill new openings with remote workers in cheaper markets.

According to a survey by the software and data firm Payscale, a little more than 60% of employers said last summer that they were not considering lowering pay for future employees who work partly or fully from home.

But a significant 14% of employers said they were planning to cut wages for teleworkers in lower-cost areas, and 17% said they were undecided.

In dollar terms, economists estimate that the value to teleworkers amounts to as much as 7.3% of their earnings.

“Some employers would like [working from home] to be seen as a benefit or a perk, and they expect employees to feel the same way,” said Laura Sherbin, a managing director at Seramount, a workplace research and consulting firm.

But the benefits of teleworking are by no means one-sided. In many cases, employers have reaped savings as well.

In addition to productivity gains, there is evidence that teleworkers actually spend more time on the job than do workers in the office. Some companies also have enjoyed savings by cutting back on rent and other expenses associated with maintaining a full-scale office.

Salaries in the U.S. have long reflected the living costs and competitiveness of the area where a workplace is situated.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

Even before the pandemic, some companies adjusted salaries for employees who requested to move to lower-cost markets. The practice has become more common in the last two years, led by tech companies, including Google, Facebook and Twitter.

Although remote workers often didn’t like the pay cut, it didn’t create a huge backlash, partly because people relocating to cheaper towns understood that they might still be able to have the same purchasing power.

But the practice raises vexing questions about workplace fairness: Should employees at the same company doing the same job be paid differently because one chooses to live in Fresno and the other in Manhattan Beach? Should workers who move to more expensive markets get a raise?

Sherbin recalled that a senior employee at one large company in Washington agreed to a big pay cut to relocate to Georgia for personal reasons and telework from there. But more than a year later, when he moved back to the Washington area, his employer refused to bump his salary back up.

“What the company said to him was, ‘But, yeah, you could have stayed in Georgia. We’re not asking you to come back to the office,’” Sherbin said.

Compensation experts say that demanding teleworkers take less pay risks undercutting the biggest gains of a remote-work option — enhancing productivity by being able to attract skilled workers and minimizing costly turnover.

“That feels like a shell game to me. I don’t like it,” said David Buckmaster, a senior compensation director at Wildlife Studios. “It could be demoralizing.”

Labor unions are beginning to take notice. In Seattle, hundreds of public employees who have been working from home since the coronavirus outbreak in 2020 recoiled at the mayor’s return-to-the-office policy, forcing the city to bargain with union representatives on telework policies.

Although Seattle’s current negotiations don’t involve pay structures for remote workers, that is something labor officials elsewhere are concerned about, seeing it as a potentially contentious issue down the road.

“Is this considered a benefit? That’s one of the things we struggle over,” said an official at the Communications Workers of America, noting that some union workers at call centers don’t have the capacity to work from home. AT&T, which recently extended its agreement with the CWA over telework, said its policies and wages have remained the same regardless of work location.

Many workers say they are willing to accept some trade-offs.

Tracey Parsons, 46, a translator for the United Nations who lives north of New York City in the suburb of New Rochelle, works three days from home and two in the U.N.’s Manhattan offices.

“I would definitely take a pay cut, not that I think it would be fair,” she said.

Parsons figures the hybrid work schedule amounts to hundreds of extra dollars a month — if she counts the money saved on train fares, lunches and everything else involved in going to the office.

But its value is potentially far bigger, she said. She and her stay-at-home husband would like to move farther north, where housing is cheaper and the couple could build a better future for their 8-year-old son, who has a disability.

“The positive consequences and benefits of this situation are enormous,” Parsons said. However, she wasn’t confident that she would be able to work three days from home on a permanent basis. The U.N. went from requiring one day in the office last fall to two days this year.

Raphael Kelly, an operations manager at FedEx, doesn’t think employers should put a monetary value on telework as they do for health benefits. At the same time, she said she would understand if companies wanted to consider working from home as part of an employee’s compensation package.

“I think it is a perk and a benefit,” said Kelly, 47, who has been working full time from her home in Haymarket, Va., since 2012. “And the perk is that you can be accessible to your family, you’re able to put your dinner on during your breaks, and it’s a benefit also because it’s work-life balance.”

Kelly manages a team of 25 people who went fully remote after the pandemic started. But since early summer, they have started returning to company buildings on a hybrid basis. “They are not happy,” she said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.