Coronavirus Today: Is it over yet?

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Jan. 11. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

One evening last week, about 200 people gathered on Olvera Street for the Día de los Reyes procession. The annual event, which dates back to the 1970s, was canceled last year at the height of the fall-and-winter surge. This year, there was a strong desire to bring it back even though coronavirus case numbers were reaching new heights.

“There comes a point where you have to get back to being with families and visitors and customers,” Valerie Hanley, treasurer of the Olvera Street Merchants Assn. Foundation, told my colleague Andrew J. Campa. “It’s important.”

Across Southern California and around the country, there’s a growing sense that people are no longer willing to keep hiding from the coronavirus. Instead, they’re doing their best to live with it.

On Olvera Street, that meant getting vaccinated, wearing masks and staying a modest distance away from members of other households. With those precautions in place, attendees commenced the procession. Then they ate Mexican sweet bread and drank champurrado.

The more time we spend with the Omicron variant — now estimated to account for more than 98% of all coronavirus specimens in the U.S. — the more it seems like a strain we can coexist with. Though it’s more contagious than its predecessors, the spike in infections hasn’t produced a corresponding rise in COVID-19 hospitalizations or deaths (at least so far).

Scientists say we’re on the right track with this thinking.

“We want to get to a place where we are no longer concerned about preventing infections, but instead worried about preventing severe symptoms and death,” Chunhuei Chi, director of the Center for Global Health at Oregon State University, told my colleague Deborah Netburn.

But we still have quite a ways to go.

How far? Here’s one way to look at it: A trio of experts suggested that COVID-19 should be no worse than other viral respiratory diseases in their most virulent years.

They used the 2017-2018 season as a reference point. That year, the flu sent 710,000 Americans to the hospital and caused 52,000 deaths. Meanwhile, respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, was responsible for 235,000 hospitalizations and 15,000 deaths.

Adding those together, the worst week of winter saw about 35,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths, the three experts wrote last week in the Journal of the American Medical Assn.

That’s still far below the current numbers for COVID-19. For the week that ended Jan. 4, the U.S. had 115,206 hospitalizations and 8,722 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID Data Tracker.

Tun-hou Lee, professor emeritus of virology at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, offered another yardstick: mortality rate. For every 100,000 people in the United States, there are 1.8 influenza deaths — and 255 COVID-19 deaths.

The 255 figure is sure to fall as immunity spreads, vaccines improve, and more treatments become available. It will surely take awhile to dip into the single digits, but at least it’s not a pipe dream.

“I think of this time as a transition,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Assn. “The virus is transitioning, and as a society we are transitioning and learning to live with it.”

That’s what they were doing last week on Olvera Street.

“People have been scared for a while, so it’s nice to see a good crowd,” said Donna Arce, a high school senior who played the Virgin Mary in the procession. “A lot of people have followed the steps, like getting vaccinated and being masked, so we should continue this tradition.”

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:50 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

The military, vaccines and politics

Back in 1998, the Defense Department added a vaccine to the list of shots service members were required to get. It was a vaccine against anthrax, and it had been licensed for use since the 1970s. The military encountered some resistance from people concerned about side effects, but only a handful opted to quit their jobs rather than roll up their sleeves.

Fast-forward a couple of decades or so to the COVID-19 era. The Pentagon urged services members to get a COVID-19 vaccine when they were able, and in August, after the Food and Drug Administration formally approved the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for people 16 and older, that recommendation became a mandate.

This time, the resistance was far more intense. My colleague Melissa Hernandez reports that according to the latest data, about 30,000 active-duty personnel are still unvaccinated. The fact that so many people would defy a military order “is a striking illustration of how deeply politicized the pandemic has become in the United States,” she writes.

It’s no secret that many Americans in the civilian world have resisted calls to be vaccinated. Challenges to President Biden’s plans for a far-reaching vaccine mandate have made it to the U.S. Supreme Court.

But in the military, a medical directive is an order that’s expected to be obeyed.

Hernandez talked to Lori Hogue, who served as a combat medic in the Army in the 1980s. Hogue recalled when soldiers were suddenly told to get flu shots. No drama ensued.

“We all knew what we had to do,” she said. “When you raise your right hand, you agree to all that stuff. You don’t have a lot of rights in the military. They tell you what to do.”

That’s been fine for the vast majority of active-duty forces. More than 97% of them have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

But that remaining 3% amounts to thousands of vaccine resisters. More than 12,000 have requested exemptions to the order on the grounds that it violates their religious beliefs. They object to the fact that cell lines derived from aborted fetuses were used to develop the shots. (As Hernandez notes, the same is true for aspirin and ibuprofen.) So far, the military has granted a grand total of zero such requests.

Others are turning to lawsuits. The Defense Department, the heads of each branch of the military and the FDA have all been sued.

Brian Stermer, a sergeant first class in the Army Reserves, is one of the plaintiffs. He said he didn’t trust the government’s assurances that the vaccines are safe and effective. Nor does he take comfort in the fact that more than 9.4 billion doses have been administered around the world, including 520 million doses in the U.S.

“It’s a new technology and there’s a nefariousness behind it,” he said.

He may have gotten that impression from the anonymous military-themed social media accounts that have been spreading misinformation about the shots. Among the false claims making the rounds is an allegation that the coronavirus is harmless to children but the vaccines have been killing them.

A handful of cadets have dropped out of the prestigious United States Military Academy at West Point to avoid the vaccine. There are also service members close to retirement who are willing to risk losing their pensions.

The Marine Corps has discharged at least 169 troops for defying the vaccine mandate. More are expected to follow when their exemption requests are denied and they run out of appeals.

The Army has reprimanded 2,767 soldiers and relieved some officers and battalion commanders of their duties. It doesn’t appear that any amount of resistance will cause the military to back down.

“We need our soldiers to be ready to fight and win,” said Lt. Col. Terry Kelley, an Army spokesman. “If this virus is spreading through our ranks, that would obviously have an impact on our readiness.”

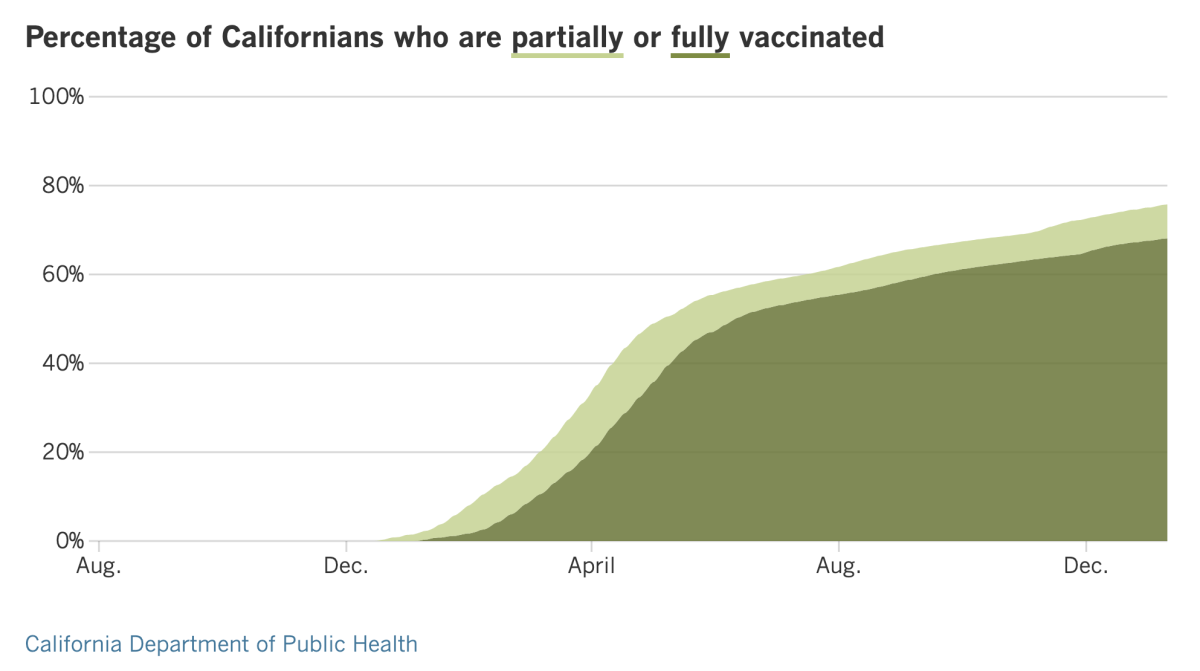

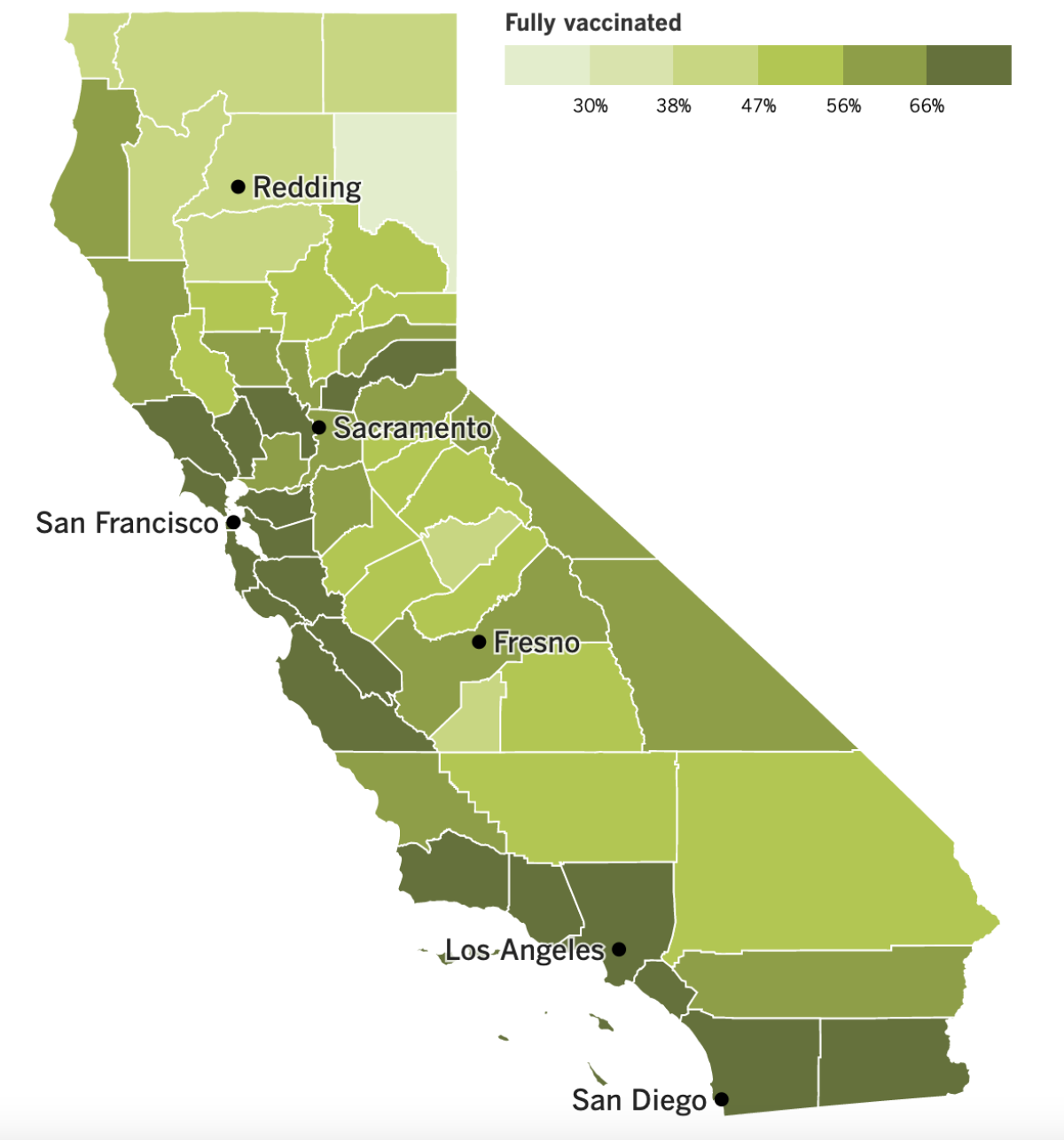

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

It’s been a week for big numbers — and it’s only Tuesday.

California recorded its 6 millionth coronavirus infection since the pandemic began, and Los Angeles County crossed the 2 million mark. Both totals are surely an undercount of the true number of infections since they don’t include the results of at-home tests, let alone people who tried to find tests but couldn’t.

It took less than eight weeks for the state’s tally to climb from 5 million to 6 million. When we hit 5 million in mid-November, new infections and hospitalizations were both on the decline. A week later, the Omicron variant burst onto the scene and changed the trajectory of the outbreak.

“Thankfully, because of the high level of immunity and vaccination protection, the rate of hospitalization is lower,” said Dr. Mark Ghaly, the California health and human services secretary. However, he added, “even with a lower percentage being hospitalized, it still means quite a bit of work, quite a bit of pressure on our healthcare delivery system.”

Indeed, the number of hospitalized patients with coronavirus infections in the state has more than tripled in the past month, reaching 11,048 on Sunday. Many of them were admitted for something else, however, and the number of critically ill COVID-19 patients isn’t rising quite as fast.

The (say it with me) grim milestone reached by L.A. County followed a new record for weekly cases (more than 200,000).

Among them were 562 members of the L.A. Police Department, Chief Michel Moore said. That’s up from 424 the previous week. As of Tuesday, 803 LAPD personnel were out of commission because they were either isolating or quarantining at home, Moore said. That’s about 6.6% of the entire LAPD workforce.

The department is still meeting its minimum patrol requirements, using overtime to ensure that shifts are being filled, Moore said. If necessary, leaves or days off could be canceled, a step the L.A. Fire Department has been forced to take.

A contingent of 200 California National Guard members have been deployed around the state to help staff coronavirus testing sites, freeing up clinical staff to remain in hospitals and clinics. More Guard members could join them at testing sites next week.

Hospitalizations in Sonoma County have nearly tripled in six days, climbing from 28 to 76 in a jurisdiction with roughly 500,000 residents. That prompted health officials to order a 30-day ban on large gatherings, beginning tomorrow. Indoor assemblies will be limited to no more than 50 people, and outdoor congregations will not be able to exceed 100.

A budget proposal from Newsom would put an additional $2.7 billion toward the state’s COVID-19 response. Some of those funds would go to hospitals, some would shore up vaccine and booster drives, and some would “battle misinformation,” the governor said. If the Legislature agrees, the first chunk of funds — $1.4 billion — would be earmarked for additional testing capacity and to fight outbreaks inside state prisons.

Back in Los Angeles, hundreds of thousands of students returned to L.A. Unified campuses Tuesday for the first time since going out on winter break. All students, teachers and staff were required to take a coronavirus test in advance of the big day, and those tests turned up more than 62,000 active infections.

According to The Times’ LAUSD coronavirus tracker, there are more than 760 schools with at least 10 cases each, and more than 140 schools with at least 100 cases each. Six high schools in the district each had more than 300 infected students and staff.

The testing requirement slowed entry onto some campuses Tuesday, but many students and parents were understanding about the delays. At Eagle Rock Junior/Senior High School, 15-year-old Jackie Pascual waited about 15 minutes as staffers checked students’ names against a paper list. Although she got a booster shot last week and was wearing a mask, she knew the coronavirus could still catch up with her.

Still, “there’s not really other options,” she said. “I obviously don’t want to get COVID, but I have to go to school.”

In Washington, D.C., members of Congress had pointed words Tuesday for the Biden administration’s pandemic response. Recent changes in isolation and quarantine guidance have made things less clear for Americans, not more, they said at a Senate hearing. Shifting views on booster shots had a similar effect.

Republican Sen. Richard Burr of North Carolina called the updates a “mess” and a “disaster.” “I’m not questioning the science,” he said, “but I’m questioning your communication strategies. It’s no wonder the American people are confused.”

Democrats joined the critique in a rare case of pandemic bipartisanship. Sen. Patty Murray complained about the lack of coronavirus tests and said some of her constituents had given up on getting tested altogether.

“People back in my home state of Washington and across the country are frustrated and worried about the course of this pandemic and its persistent challenges,” she said.

In a (surely unintentional) demonstration of the administration’s confused messaging, some speakers — including Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Dr. Janet Woodcock, acting commissioner of the FDA — kept their masks on during their testimony, as requested by Murray. But Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, removed his KN95 mask when addressing the senators.

Here’s a Biden administration initiative that even some of his critics are sure to like: Starting Saturday, health insurers will have to pay for up to eight home COVID-19 tests per month for people they cover. That means a family of four could get up to 32 tests per month.

Test kits can be obtained for free, or plan members can buy them on their own and submit claims for reimbursement. (Insurers still have to cover the full cost of PCR and rapid tests ordered or administered by health providers.) And by the end of the month, the federal government will begin mailing 500 at-home test kits to people who request them online.

L.A. County launched its own to-go testing program on Monday. Residents can pick up a PCR test kit, take their own swab and return it to a designated site for processing. More than 6,000 tests are expected to be available each day.

And finally, longtime COVID-19 vaccine backer Pope Francis has ratcheted up his rhetoric. We all have a responsibility to take care of ourselves, he said Monday, “and this translates into respect for the health of those around us. Healthcare is a moral obligation.”

It was the first time he had spoken of vaccination in moral terms. Previously, he said getting the shots was “an act of love” and that refusing them was “suicidal.”

The 85-year-old pontiff also lamented the toxic combination of partisanship and misinformation that has dissuaded people from getting vaccinated.

“Frequently people let themselves be influenced by the ideology of the moment, often bolstered by baseless information or poorly documented facts,” he said. To fix this, he called for the adoption of a “reality therapy.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Why is it so hard to find a rapid coronavirus test?

After all, the first such tests — made by Abbott Laboratories and Quidel Corp. — were authorized for emergency use by the FDA back in March. Test kits made by at least 10 more companies have been authorized since. Surely that should have been enough time to produce all the test kits we could possibly need.

Time isn’t the problem here. It’s a simple matter of supply and demand.

Before the Delta surge came along, consumers didn’t see much need for the tests — vaccinations were rising and infections were falling. Companies didn’t want to spend money making tests unless they felt confident they could sell them. So instead of ramping up their production, they did the opposite.

Abbott, the biggest player in the market, closed one plant and shut down two production lines at another. Other companies made similar moves.

So when Omicron upended everything and more people wanted to test themselves more often, the kits sold out quickly.

Now that demand is back up, once-idled production lines are running. Even the shuttered factory is back in business.

But it takes a little while to get up to full speed. Abbott said it could make 70 million tests in January and perhaps 100 million in February. Quidel said it could make 600 million tests over the course of a year.

One way to keep the pendulum from swinging back again is for the federal government to place a large order. That way, companies can afford to keep churning out tests without worrying about demand sinking. That’s one reason the Biden administration is buying 500 million test kits

For what it’s worth, the U.S. isn’t the only country grappling with a shortage of at-home tests.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.