Coronavirus Today: Why things are getting worse

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, May 31. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Just a few short months ago, the end of the pandemic seemed close at hand. The Omicron wave was in the rearview mirror, leaving widespread immunity in its wake. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated the way it measures COVID-19 risk and determined that 72% of Americans lived in counties where indoor masking was no longer necessary. The term “endemic” entered our vocabulary.

And let’s not forget the ultimate metric of pandemic progress: This newsletter reduced its frequency to once a week.

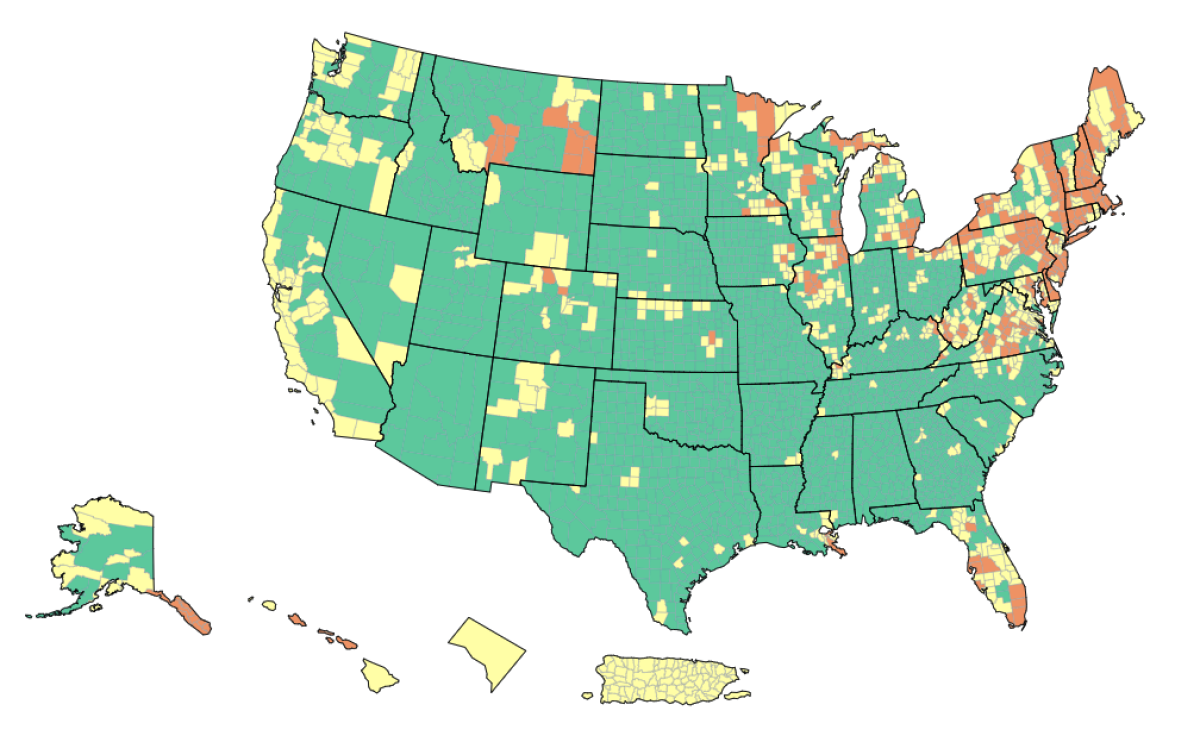

Now the coronavirus is making a comeback. In California, 19 counties lost their status as having “low” COVID-19 community levels and were bumped into the “medium” category, indicating a greater degree of risk. After the CDC’s updated assessment on Thursday, 78% of the state’s residents lived in “medium” counties — a list that includes Los Angeles and Orange counties, the entire San Francisco Bay Area, and every single county along the coast.

The East Coast looks even worse. From Maine to Virginia, counties with “high” COVID-19 community levels are just as common — if not more so — as counties in the “medium” and “low” tiers. Counties with “high” community levels are also prevalent in the Midwest and in Florida.

How did we get here? A pair of infectious-disease experts lay out several factors in a commentary published Friday in the Journal of the American Medical Assn.

Dr. Carlos del Rio of Emory University and Dr. Preeti N. Malani of the University of Michigan start with Omicron and its many subvariants. The original Omicron variant sparked an unprecedented surge that saw the seven-day average of new cases peak above 800,000 per day, more than three times higher than the worst days of the previous winter’s devastating surge. Deaths during the Omicron wave weren’t quite as high as they’d been the previous year, but at its height, the country was averaging more than 2,700 COVID-19 deaths per day.

Unfortunately, Omicron didn’t rest on its laurels. The original BA.1 strain has been followed by a series of subvariants that have spread even more readily than its highly transmissible forebear.

BA.2, for instance, has 29 mutations on its spike protein. Those changes make it more difficult for an immune system familiar with an earlier version of the coronavirus to recognize this incarnation. As a result, BA.2’s effective reproduction number — a measure of how many people will catch the virus from one infected person — is 40% higher than BA.1’s.

As if that weren’t bad enough, BA.2 spun off another subvariant, called BA.2.12.1. It includes a mutation seen in the Delta and Lambda variants that helps the virus latch onto key receptors on human cells “and thus become more transmissible,” Del Rio and Malani write.

BA.2.12.1 is now the dominant coronavirus strain in the U.S., accounting for an estimated 59% of infections during the week that ended Saturday. One reason for its success: A previous bout with the original Omicron — let alone with Alpha, Beta or Delta — doesn’t do much to protect people from BA.2.12.1, the pair write.

The same goes for the subvariants known as BA.4 and BA.5, which the World Health Organization considers variants of concern. These two haven’t gained much traction in the U.S., but that could change.

The Omicron offspring have also proved adept at overcoming immunity generated by vaccines. Getting two doses of Comirnaty or SpikeVax “provides limited protection” against COVID-19, Del Rio and Malani write. Protection “increases substantially” with a booster shot, though the benefit begins to wane “within months,” they add. For most people, following up with a second booster doesn’t do much to improve the situation.

That’s not to say the vaccines are useless, the pair point out: “As is the case with other vaccines, the goal of vaccination against COVID-19 is to protect against serious illness, not prevent all infections.”

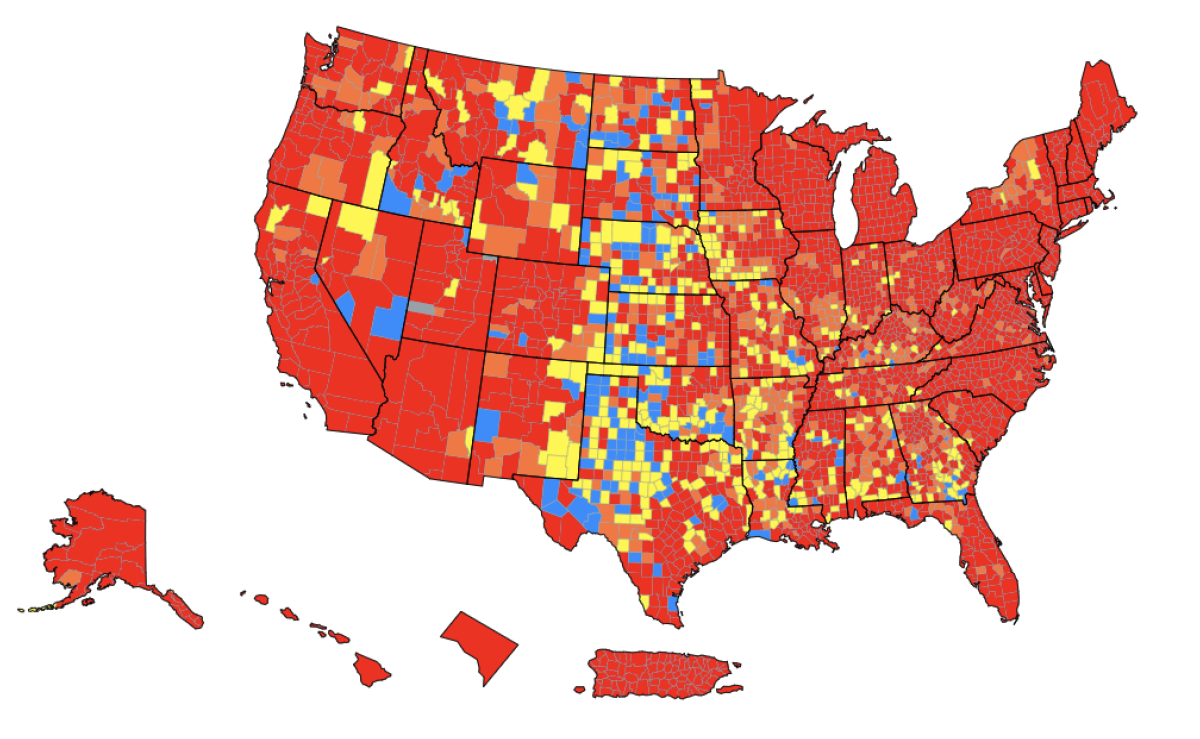

If you’re not inclined to bury your head in the sand, these trends sound like something to worry about. But it’s easy to miss the big picture. That’s because the CDC has multiple ways of conveying risk, and they paint wildly different pictures of the current state of the pandemic.

Let’s go back to the COVID-19 community levels mentioned earlier. That measure is designed to gauge whether local healthcare systems are at risk of being inundated by seriously ill COVID-19 patients — a situation that would put anyone needing medical attention for any reason in jeopardy. It also accounts for the fact that official case counts are less reliable now that so many people are testing at home (and not necessarily reporting the results).

Based on COVID-19 community levels, fewer than 8% of U.S. counties were in the “high” category as of Tuesday. Yet at the same time, two-thirds of U.S. counties have “high” levels of community transmission, another CDC metric that combines the number of new cases per 100,000 people over the past week with the positivity rate for coronavirus tests that confirm an infection by looking for viral RNA.

The CDC says it publishes the community transmission rates for the sole benefit of healthcare facilities and encourages the general public to let COVID-19 community levels guide them in determining how cautious they should be about walking into a grocery store without a mask or dining inside a restaurant. Del Rio and Malani see that as a big mistake.

“The existence of 2 different CDC metrics that provide almost opposing information adds to confusion and makes recommendations on the use of nonpharmacologic interventions, such as masking, more difficult,” they write. “In addition, focusing on the COVID-19 Community Levels metric contributes to the myth that the pandemic is over, something everyone wants to believe is true but certainly is not.”

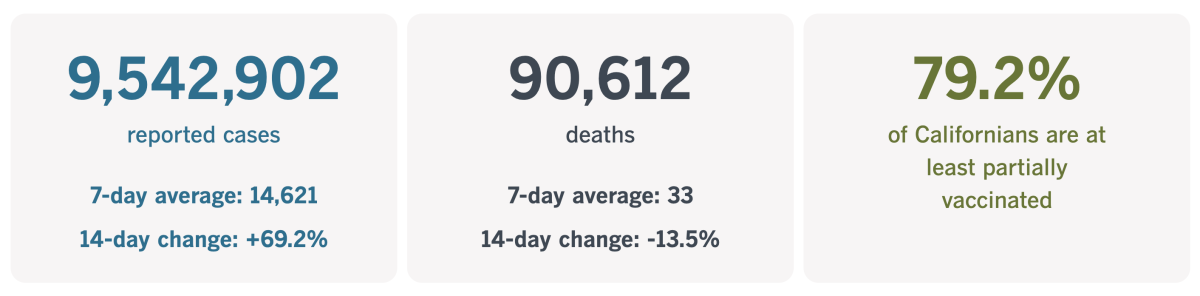

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:35 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

A reset for restaurant workers

“Resilient” is a word many of us have come to associate with the pandemic. It describes people who have battled illness or are still coping with the aftereffects. It applies to those who have carried on with their lives after losing loved ones. It covers the doctors, nurses and therapists who put their own health at risk to help others heal. And it extends to people who lost their livelihoods when COVID-19 turned the economy upside-down.

Restaurant employees were in a unique spot. On the one hand, they were hailed as essential workers — especially in the early lockdown days when we became well acquainted with apps like Doordash and Grubhub. But they were also being laid off in droves — nationwide, about 5 million people lost jobs at restaurants and bars in March 2020.

My colleague Samantha Masunaga caught up with former restaurant workers who used the pandemic to take a time out from their careers and reassess their priorities. Some of them stayed in the industry but upgraded their jobs; others found entirely new paths. Their stories are a reminder that silver linings are everywhere.

Gaby Mlynarczyk is a prime example. The 55-year-old had been bartending since she was in college, and for decades she thrived.

“There’s an energy of working in a restaurant or a bar — it’s different every single day,” she told Masunaga. “It can be a little bit of a grind at times, but you meet such amazing people working in restaurants and bars.”

Her relationship with customers changed after the pandemic hit. Mlynarczyk was working at a cafe-bar in Playa Vista and noticed that patrons had stopped tipping. The following year, when working as bar director of a pop-up, a patron who couldn’t get into an event because of COVID-19 capacity limits spat on her mask. It was the final straw.

“I got home that night, and I was just like, ‘That’s it. I can’t do this anymore,’” she said.

She isn’t. Mlynarczyk now works as a brand ambassador for a Napa aperitif company, promoting the product throughout Southern California. She makes more money and has a boss who respects her opinions.

Karen Fu had a similar epiphany. Before the pandemic, she was so committed to her work that she’d put in 10- to 12-hour days managing staff and guests, even when recurring ankle injuries made it difficult to stay on her feet. She was finally forced to rest when she was furloughed at the start of the pandemic.

The unexpected break taught her to cherish her personal time. When she had the chance to come back to work, she declined — on multiple occasions.

Instead, she devoted herself to volunteering for the Restaurant Workers Community Foundation. She now serves on the board of directors and co-chairs the grant-writing and nonprofit partnerships committee. It’s “more viable and productive in terms of giving back to the industry that I do love and enjoy being a part of,” Fu said.

She had hoped to make a new career out of nonprofit work, but the right opportunity hasn’t come along yet. So she took a job managing bar operations at a hotel in Beverly Hills. The pay is better, she has health insurance, and her schedule is more balanced.

“It has felt right,” Fu said. “I hope to make effective change from within.”

Schuyler Mastain decided to leave his job as a waiter at Rossoblu in downtown L.A. not because of his bosses or customers. It was because the pandemic inspired him to “recession-proof” his life.

“Restaurants feel volatile,” the 39-year-old remembers thinking. “My job feels like it’s not going to be here tomorrow. I need something where I can provide for a wife and, hopefully, children.”

So in August, he quit Rossoblu and started teaching English to high school students. The pay is actually lower — about $900 a month less — but that will change as he moves up the pay scale. To bolster his bank account, he plans to return to the restaurant this summer while school is out, then will begin teaching drama full-time at a high school in the L.A. Unified School District.

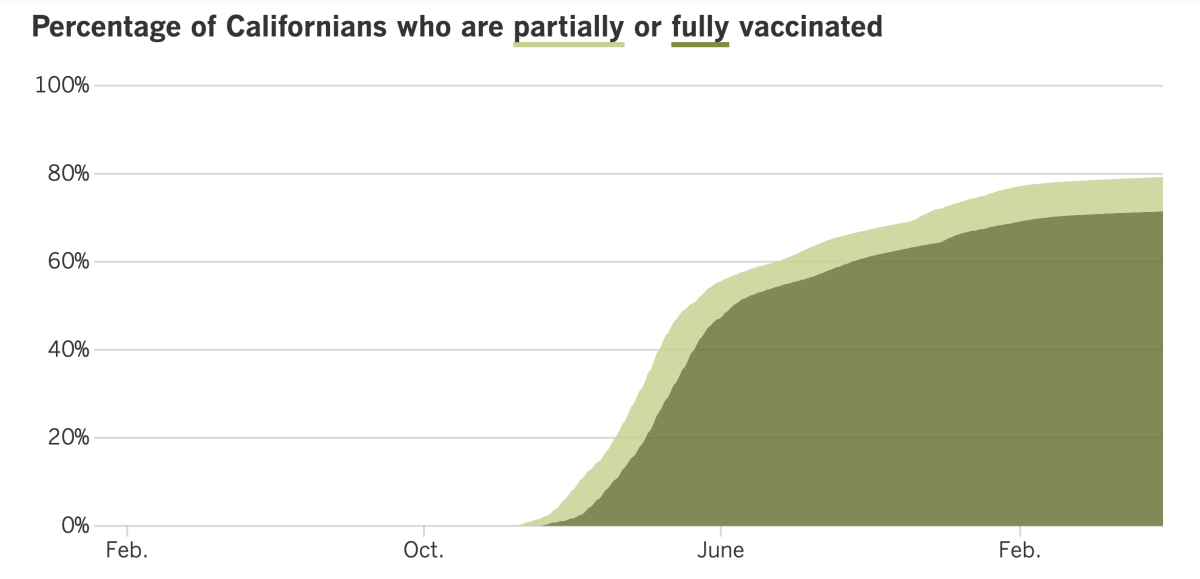

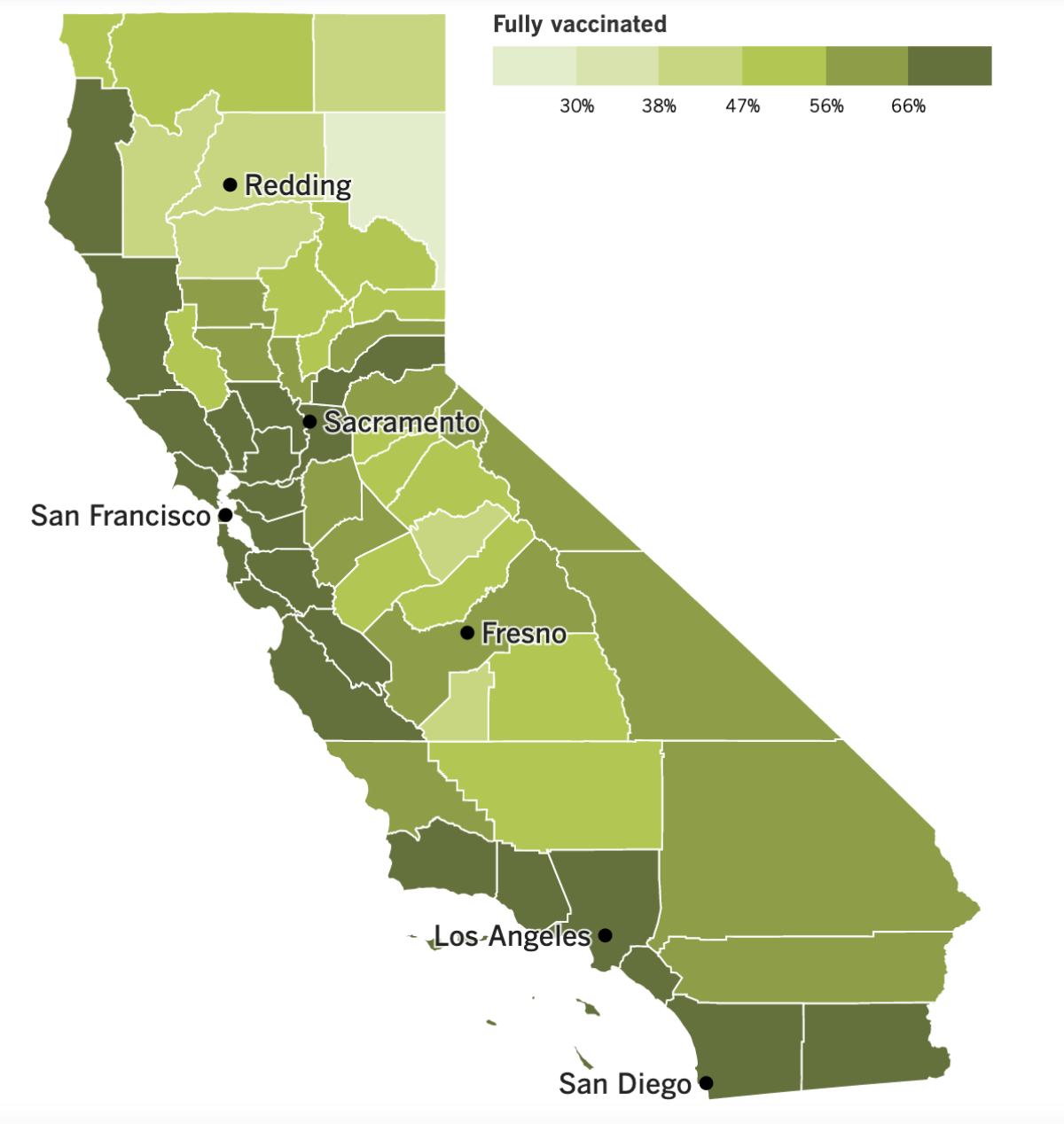

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

The reality of the coronavirus situation is beginning to set in, prompting UCLA and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo to reinstate indoor mask mandates.

Cal Poly SLO brought back its mask rule Tuesday in an effort to counteract the school’s rising caseload. It applies to all students, employees and visitors — even those who are vaccinated and boosted.

“When we informed the campus community in February that we were lifting the campus’ indoor mask mandate, we indicated that we would monitor health and safety conditions and would reinstate the mandate should those conditions require it,” explained Anthony J. Knight, Cal Poly’s executive director of public safety. “Unfortunately, that time has come.”

UCLA restored its mask rule on Friday and said it would remain in place at least until June 15. It applies to students, faculty, staff, visitors and anyone else on campus, regardless of vaccination status.

The indoor mask order is “an important strategy to curb the spread of COVID-19,” school officials explained in a letter posted Thursday. The hope is that by wearing masks, students can safely finish the quarter without canceling in-person classes, and that graduation ceremonies will go off as planned.

L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said she thought UCLA’s mask rule would make a difference. Despite her endorsement, she said a similar mandate for the county as a whole was not in the cards unless COVID-19 patients started putting serious strain on the region’s hospitals.

Dr. Ashish Jha, the White House COVID-19 coordinator, made an interesting observation last week about the nationwide increase in coronavirus cases: This is the first time since the start of the pandemic that an increase in infections has not been accompanied by an increase in deaths.

“What has been remarkable ... is how steady serious illness and particularly deaths are eight weeks into this,” he said. “COVID is no longer the killer that it was even a year ago.”

The Biden administration hopes to keep it that way by making the anti-COVID drug Paxlovid more accessible across the country.

Federally sponsored test-to-treat sites are being opened in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New York City and Minnesota, all hard-hit areas. Regulators are also hoping to increase the uptake of Paxlovid by sending clearer guidance to doctors about how the antiviral interacts with other drugs. High-risk patients who begin taking Paxlovid within days of becoming infected can reduce their chances of hospitalization or death by about 90%.

“We are now at a point where I believe fundamentally most COVID deaths are preventable,” Jha said, “that the deaths that are happening out there are mostly unnecessary.”

Elsewhere in the nation’s capital, inspectors general from various government agencies told members of Congress they needed more authority to go after fraudsters who had taken advantage of COVID-19 relief programs.

Currently, the IGs can administratively prosecute cases only if they involve $150,000 or less; anything above that amount falls to the Department of Justice. But the DOJ rarely bothers with cases worth less than $1 million. That gap leaves plenty of significant frauds unpunished, the IGs said.

Their proposed solution is to raise the limit on fraud claims they can handle administratively to $1 million. And would you believe there is bipartisan support to do just that? Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) is sponsoring a bill that would make the change, and Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) is its co-sponsor.

In other legislative news, lawmakers in Louisiana are working on a bill that would prevent governments and state-run educational institutions from requiring proof of COVID-19 vaccinations to enter their buildings. Those that do would face fines.

Opponents of the bill say local governments shouldn’t be penalized for trying to contain coronavirus spread. But they seem to be outnumbered by those who say governments shouldn’t be inquiring about individuals’ health history.

On the research front, a report out last week from the CDC suggests that senior citizens face a higher risk of long COVID compared to younger adults. Among people 65 and older who had COVID-19, 1 in 4 still had symptoms up to a year after they became infected. Among younger adults, 1 in 5 had lingering symptoms.

The most common problems included difficulty breathing and muscle aches. In addition, seniors were more likely to suffer strokes, brain fog, kidney failure and mental health problems.

Over in North Korea, officials are proclaiming a stunning success in quashing their COVID-19 outbreak, and outsiders say it’s literally unbelievable.

The famously secretive country said 3.3 million citizens had had coronavirus infections bad enough to cause fevers but only 69 of the patients had died. If true, that would be a fatality rate of 0.002%, something no other country has achieved.

“This evidently proves the scientific nature of our country’s emergency anti-epidemic steps,” North Korea’s main newspaper said Thursday.

Medical experts are highly skeptical. North Korea has limited access to COVID-19 vaccines, so most citizens are unvaccinated. In South Korea, the fatality rate for unvaccinated people infected with Omicron has been 0.6% — 300 times higher than what the North claims.

“Scientifically, their figures can’t be accepted,” said a professor from South Korea’s Ajou University Graduate School of Public Health.

And finally, I have a clarification regarding the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine. Last week I mistakenly implied that the vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna are made from fetal tissue. As we’ve discussed in earlier editions, fetal tissue was used to develop and test those vaccines, but it’s not an ingredient in the actual shots.

Your questions answered

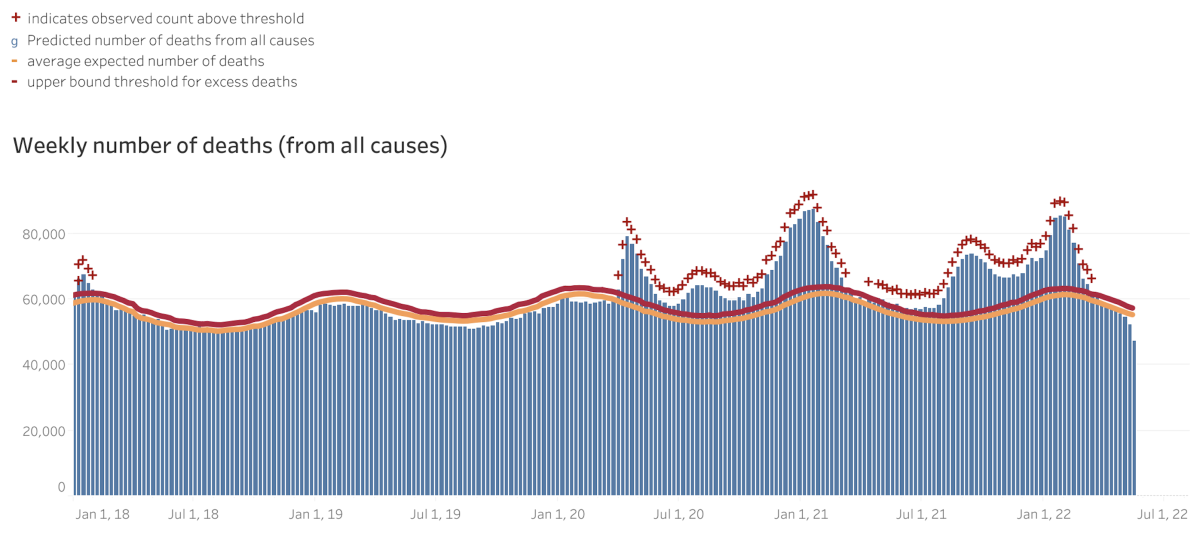

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Is COVID-19 increasing the country’s overall death rate?

This is another question we received after marking America’s 1 millionth COVID-19 death earlier this month. Several readers wondered whether the people who were killed by the new disease would have died of something else if the coronavirus hadn’t come along.

Among the country’s 1-million-plus COVID-19 victims, there are surely some who would have died over the last 2½ years even in the absence of the pandemic. But most of them would still be alive.

How can we know? One way is by counting “excess deaths.” This statistic compares the expected number of deaths in a given period of time with the actual number of deaths that occurred. Any deaths over and above the expected number are considered “excess.”

This graph from the CDC shows that the number of excess deaths per week, starting in January 2018. At first, the number of observed deaths (in blue) matched the expected number (represented by the orange and red lines) quite nicely. That changed at the tail end of March 2020, when the observed deaths suddenly jumped above the expected curve. Between Feb. 1, 2020, and March 14, 2022, the total number of excess deaths in the U.S. was 1,124,728.

Not all of these unexpected deaths were due to COVID-19, but most of them probably were — there’s just no other way to account for the sudden and often dramatic increase in weekly fatalities.

Here’s another way to look at it: The annual number of U.S. deaths rose by an average of 1.63% per year between 2010 and 2019, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. During that pre-pandemic decade, the largest single-year increase was 3.28% (seen in 2015).

Then along came 2020, and the total number of U.S. deaths increased by nearly 19% compared to the year before. It was the biggest year-to-year jump in 100 years.

COVID-19 didn’t exist in the U.S. in 2019. But in both 2020 and 2021, it was the third-leading cause of death, according to the CDC.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The photo above was taken Friday in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, when Gov. Gavin Newsom and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Arden pledged to work together to tackle climate change.

The next day, Newsom became one of California’s 9.5 million coronavirus cases.

“This AM, I tested positive for COVID-19 and am currently experiencing mild symptoms,” he tweeted on Saturday. “Grateful to be vaccinated & for treatments like Paxlovid.”

His infection is a testament to how much work it takes to steer clear of the coronavirus. Not only is Newsom vaccinated but he’s also received two COVID-19 booster shots, including one on May 18. The 54-year-old governor will work remotely while he isolates until Thursday, and perhaps longer.

Some members of the New Zealand delegation caught the coronavirus around the same time as Newsom. But Arden was fine — she had a mild case of COVID-19 two weeks ago. On Tuesday, she met with President Biden at the White House to discuss the gun control measures passed in her country after an armed white supremacist in Christchurch killed 51 Muslims.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.