Oil put L.A. on the map. It may have exaggerated the city’s quake risk too

- Share via

Hoping to escape traffic on her way home from Los Angeles International Airport, Susan Hough found herself driving down La Cienega Boulevard through the heart of the Inglewood Oil Field. It was a jarring scene: Scores of black pump jacks nodded lazily in the scrubby hills, like a herd of mechanical giraffes.

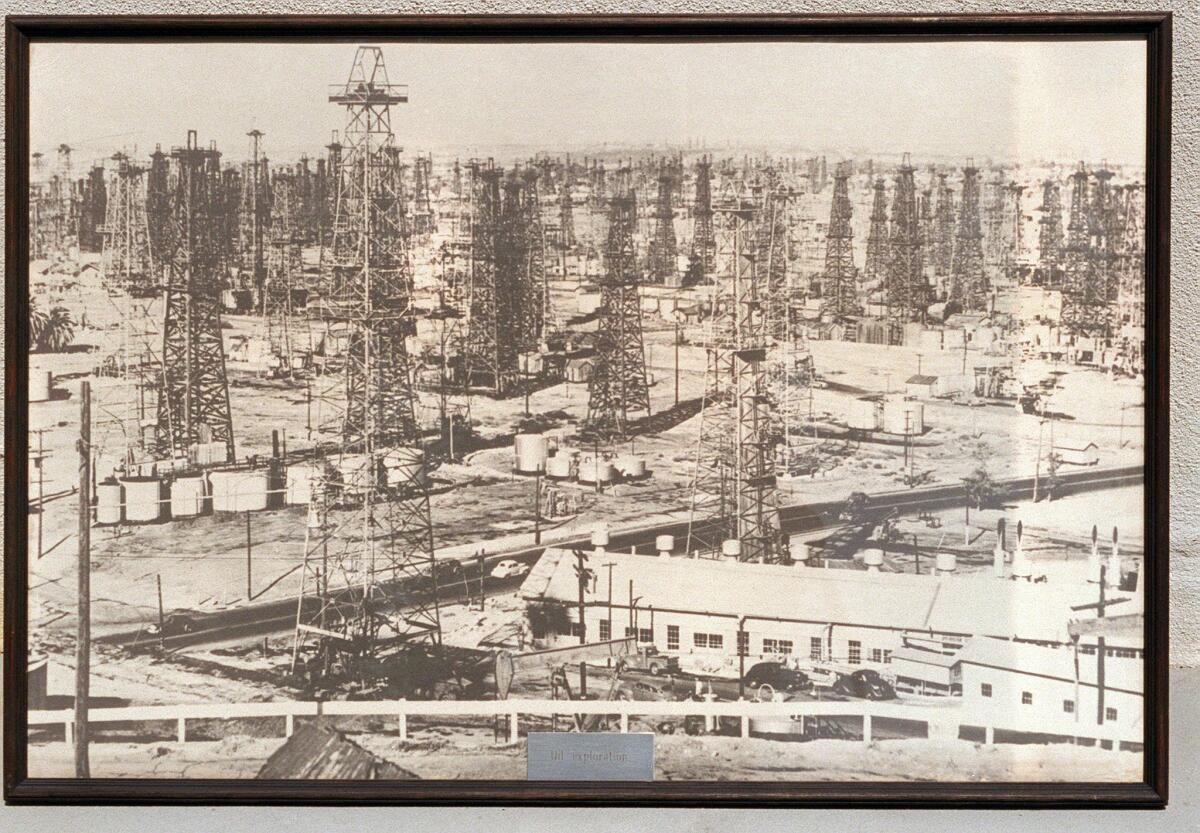

One hundred years ago, this would have been a common sight. Rows of derricks once stood watch over Huntington and Venice beaches. The spindly towers crowded the top of Signal Hill and flanked the La Brea tar pits.

Oil put Los Angeles on the map, and by the 1930s, the city helped California produce nearly a quarter of the world’s supply.

But Hough, a geophysicist at the U.S. Geological Survey in Pasadena, thinks there may have been another consequence of all that pumping. Her research suggests it could have caused nearly all of the moderate earthquakes that struck the Los Angeles Basin in the first half of the 20th century, which have previously been attributed to geologic forces.

If true, that could be good news for the region.

“The L.A. Basin could be a generally safer place for natural earthquakes than what we’ve estimated,” Hough said.

Hough has spent years investigating possible links between oil extraction and seismicity. She and her colleagues have analyzed historical damage reports to determine the exact locations of earthquakes that occurred before high-quality seismic monitoring began in the 1950s. They’ve also pored over detailed oil production data for the Los Angeles region to calculate how pumping would have affected local faults.

Again and again, the researchers found suspicious connections.

“The earthquakes are darts, and they are falling pretty close to the bull’s-eyes where the stress changed,” said Hough, whose latest study on the subject was published late last year in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

The idea is controversial. It’s difficult to determine the precise cause of any earthquake, especially one that occurred so long ago. And as scientists often say, correlation is not causation.

But Jenny Suckale, a geophysicist at Stanford University, said Hough and her colleagues have done good detective work.

“They really tried to pull together the various pieces,” said Suckale, who was not involved in the research. It “might seem like the obvious thing to do, but it’s not often done — not in that level of completion.”

‘The same story over and over’

Human-induced earthquakes have rocked states such as Oklahoma and Texas in recent years as oil and gas production there has soared. That got Hough wondering whether anything similar had happened during L.A.’s oil boom in the first few decades of the 20th century.

There were no seismometers back then, but there were plenty of people around to feel the flurry of earthquake activity. After an event, postmasters distributed questionnaires to residents asking whether the shaking rattled their china or knocked them over. Newspapers reported where the worst damage occurred.

Decades later, this information allowed researchers to estimate the strength and location of historical earthquakes. And in 2016, Hough and her USGS colleague Morgan Page published a study proposing that oil extraction may have caused many of L.A.’s early 20th century earthquakes. The events occurred close to oil fields, and they tended to coincide with changes in activity there, the researchers noted.

A magnitude 5 quake in 1920 that toppled chimneys and brick facades in Inglewood occurred soon after the discovery of natural gas at a local oil field. Another that struck Whittier in 1929, knocking houses off their foundations, hit after production ramped up at the nearby Santa Fe Springs oil field.

By far the most significant was the 1933 Long Beach earthquake. The magnitude 6.4 event killed at least 120 people; destroyed houses, churches and schools; and damaged buildings 30 miles away in downtown Los Angeles. It came about six months after Superior Oil Co. drilled into a 4,000-foot-deep deposit off Huntington Beach.

Hough said that the two events may have been linked but that it’s impossible to say for sure. “We just have the spatial and temporal association,” she said.

Soon after the Long Beach temblor, scientists finished installing the first network of seismometers around Los Angeles. When the war effort touched off another oil boom in the late 1930s and early ’40s, the devices recorded eight more moderate earthquakes.

Researchers could then use seismic data to locate the epicenters, but Hough said the results weren’t very reliable and often conflicted with where people reported the strongest shaking.

So she and Roger Bilham, a seismologist at the University of Colorado, consulted newspapers and shaking reports to refine the locations of these events. Some were off by as much as five miles, they found.

Once the records were corrected, the researchers noticed that all of the earthquakes fell close to active oil fields. And when Hough and Bilham factored in oil industry data, they saw that quakes tended to occur after an increase in production or the deepening of wells.

For instance, a magnitude 4.5 event shook the port just after Christmas 1939, stopping clocks and producing a deep roaring sound that unsettled Malibu residents. It struck soon after extraction ramped up at the Wilmington oil field, one of the largest in the region.

Then, in the fall of 1941, a temblor occurred close to the Dominguez oil field, where a new well had recently hit oil two kilometers beneath the surface.

“You see the same story over and over with these earthquakes,” Hough said.

The researchers also modeled how pumping would have changed the stresses on local faults. By 1940, it would have started to affect rocks at the depths where earthquakes occurred, they found.

It’s not proof, but the calculations bolster the argument that oil extraction was capable of causing earthquakes in the L.A. Basin, said Gillian Foulger, a geophysicist at Durham University in the U.K. who was not involved in the study.

“They’ve done an extremely impressive piece of work,” she said.

Oil pumping leads to sinking — and shaking

If these quakes were caused by oil extraction, they happened for different reasons than the ones in Oklahoma, Hough said. There, the culprit seems to be the large amounts of oil and gas wastewater that are injected deep underground. This can increase the pore pressure on faults, making it easier for them to slip.

Oil extraction, on the other hand, should cause pore pressure to decrease, reducing the chance of an earthquake. But it can have other consequences.

“If you suck oil out of a reservoir,” Bilham said, “what you’re effectively doing is removing the support for all the rocks above it.” That can cause sinking — and shaking.

It’s a phenomenon scientists have noticed at oil and gas production sites around the world, Suckale said. In the Netherlands, protests over a rash of induced earthquakes prompted the government to announce the closure of a massive natural gas field.

The same thing may have happened in Los Angeles.

Consider the Wilmington oil field, where pumping created a miles-wide depression. It nearly swallowed the Southern California Edison electric plant on Terminal Island and buckled rail lines leading into the port. As the problem worsened, the Navy warned it would have to close its increasingly soggy shipyard if oil extraction didn’t slow down. By 1958, some areas had dropped more than 25 feet.

Finally, business leaders brokered a solution.

Oil companies began injecting water underground to counteract the sinking and to boost oil production in depleted wells. Water flooding, as the practice was known, soon became standard.

The Los Angeles Basin hasn’t seen nearly as much earthquake activity since the middle of last century, even though the district still produces 23 million barrels of oil a year. Hough said that may not be a coincidence.

Water flooding could have stabilized the stress on faults, she said. Or extracting all that oil may have finally caused the faults to clamp shut because of decreased pore pressure.

Either way, Hough’s studies and others suggest there aren’t many other sizable earthquakes in the last 100 years that don’t have some circumstantial connection to oil, she said.

Hough knows her ideas are contentious. “Induced earthquakes have been something of a third rail in seismology for a long time,” she said.

Her findings conflict with a 2015 study led by Caltech seismologist Egill Hauksson that found no evidence for a clear link between oil extraction and earthquakes in L.A.’s past. But that analysis spanned 80 years from 1935 to 2014, a period that saw big changes in drilling techniques. And Hauksson’s team used the original locations for historical earthquakes.

John Vidale, a USC seismologist and director of the Southern California Earthquake Center, said the different conclusions could also reflect the researchers’ willingness to go out on a limb.

“Sue does like to make claims that are speculative,” he said. “And most of them have held up.”

Vidale agrees that this one is plausible. It’s not the only possible explanation for the cluster of 20th century seismic events, he said, but “the association of the earthquakes with oil withdrawals seems reasonable and at least halfway convincing.”

If Hough and her colleagues are right, the Los Angeles Basin may be less seismically active than scientists thought.

“It would downgrade the rate at which we expect big earthquakes,” Vidale said.

Clearly, as the 6.7 Northridge quake in 1994 demonstrated, the Greater Los Angeles region faces very real seismic risks. And the faults that crisscross the city continue to move, which means they remain a danger no matter what caused earthquakes in the past, Hauksson said.

But one thing is certain: The early earthquakes — especially the 1933 Long Beach event — awoke Californians to the dangers beneath their feet. Even if the disaster was caused by oil drilling, it catalyzed efforts to impose stricter building codes and other seismic safety measures.

“That earthquake in particular has made everything safer moving forward,” Hough said.