NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft is awake and cruising toward Pluto

- Share via

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft is awake and doing fine.

The spacecraft bound for Pluto roused itself from its latest hibernation on Saturday at noon PST. One and a half hours later, it sent a radio signal to Earth to confirm it had successfully turned itself back on.

The spacecraft is currently 2.9 billion miles from our planet, so even though the signal was traveling at the speed of light, it took 4 hours and 26 minutes for it to reach NASA’s Deep Space Network in Canberra, Australia. Mission operators at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory confirmed that New Horizons was indeed in “active mode” at 6:53 p.m. PST.

“Technically, this was routine, since the wake-up was a procedure that we’d done many times before,” said Glen Fountain, New Horizons project manager at APL in a statement. “Symbolically, however, this is a big deal. It means the start of our pre-encounter operations.”

New Horizons has spent the past nine years traveling through nearly 3 billion miles of space. For two thirds of that time it was in a state of half-sleep. A few of its instruments continued to collect data about the solar wind and dust particles in the interplanetary emptiness, and a beacon allowed scientists to track its movements through space.

NASA woke New Horizons up at least twice a year to check its instruments and practice maneuvers it will make around Pluto. After this wake-up, however, the spacecraft will not be going back to sleep. It will begin to make distant observations of Pluto on Jan. 15.

Considering that Pluto is right here in our solar system, scientists know remarkably little about it. It was first spotted in 1930, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that astronomers started to realize that it was not alone in its distant orbit. Instead, it is part of a complex system of more than 1,000 bodies called the Kuiper belt.

To this day, experts are divided on whether Pluto can even be called a planet.

“The geophysical definition of a planet is that the object has enough mass that its gravity holds it in a perfect sphere,” said Harold Weaver, of Johns Hopkins and the principal project scientist on the mission. “Pluto is almost a perfect sphere, and on this mission we will find out if has enough mass that it deserves to be in the planet category.”

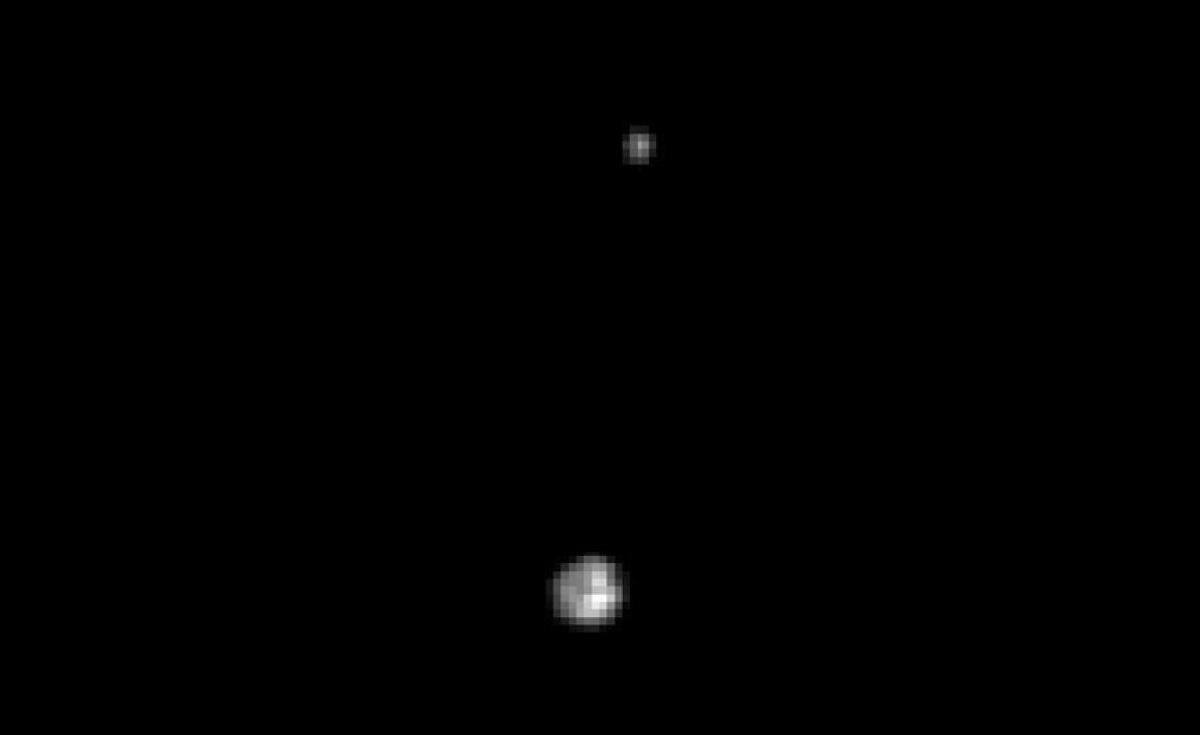

Also, no one really knows what it looks like. Neither of the Voyagers visited Pluto on their journey through the solar system. That sad pixelated picture above is the best image of Pluto and its moon Charon ever taken. It was taken by the Hubble telescope in 1994.

But all this lack of knowledge is about to change. Over the course of New Horizon’s mission, high-definition cameras on the spacecraft will capture such detailed pictures of Pluto that you could easily spot a feature the size of a pond in New York City’s Central Park on its surface.

Other instruments will study the chemical makeup of Pluto’s atmosphere and surfaces, map its topography, see how it reacts with the solar wind, and look for rings.

“We are so very looking forward to turning this very fuzzy little image of a distant planet into something real,” said Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute, and the principal investigator of the New Horizons mission. “Our knowledge of Pluto is like our knowledge of Mars, 50 years ago.”

The spacecraft still has a ways to go before it reaches its destination. It is currently 162 million miles from Pluto. At its closest approach to the planet in July 2015, the spacecraft will get within 7,700 miles of Pluto’s surface.

But for researchers on the project, Saturday’s wake-up call was an important milestone.

“The final hibernation wake-up Dec. 6 signals the end of a historic cruise across the entirety of our planetary system,” said Stern in a statement. “We are almost on Pluto’s doorstep!”

Science rules! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.