When masculinity turns ‘toxic’: A gender profile of mass shootings

- Share via

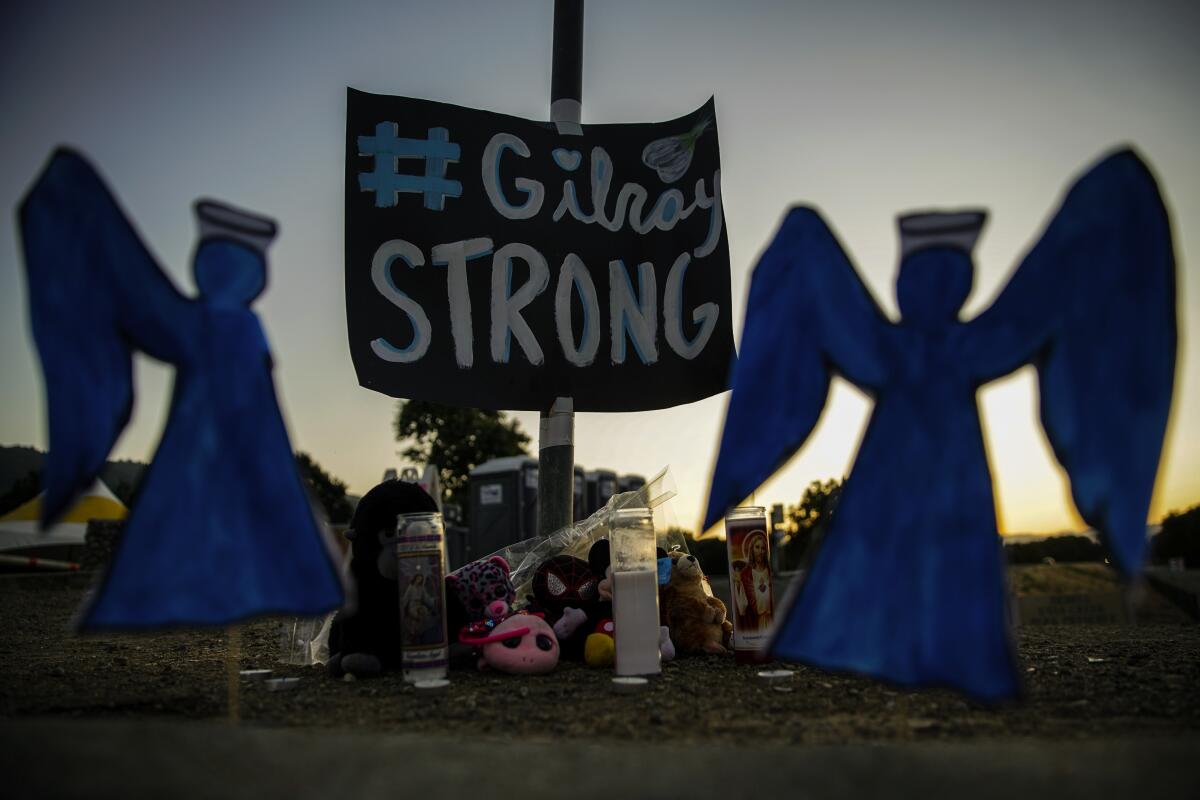

Soon after a 19-year-old man killed three people and wounded more than a dozen others at a festival in Gilroy, Calif., in late July, California Gov. Gavin Newsom noted something often taken for granted about mass shootings.

“These shootings overwhelmingly, almost exclusively, are males, boys, ‘men’ — I put in loose quotes,” Newsom said during a news conference. “I do think that is missing in the national conversation.”

Between January 2013 and August 2019, there were 11 shooting rampages in California in which the perpetrator indiscriminately shot victims in public places and killed three or more people, according to an open source database maintained by the nonprofit news organization Mother Jones. Nine of those mass shootings involved a sole male suspect, one involved a sole female suspect, and one involved a male and a female couple who killed 14 and wounded 21 others in San Bernardino.

Nationwide, there were 53 indiscriminate mass shootings in public areas during that time, and all but three involved male suspects. (The Mother Jones database excludes murders motivated by robbery, gang violence or domestic abuse in private homes.)

Newsom had his explanation for the difference. “I think that goes deep to the issue of how we raise our boys to be men, goes deeply into values that we tend to hold dear: power, dominance and aggression over empathy, care and collaboration.”

Here’s what a range of experts had to say about what might explain the gender disparity.

Eric Madfis, an associate professor of criminal justice at the University of Washington-Tacoma, said research shows that men who commit mass murder tend to feel their masculinity has been diminished in a fundamental way.

“So, there are people who have been rejected by lots of girls, or ignored by friends or by peers ― people who have experienced lots of job losses,” said Madfis, who wrote a study on the common traits of mass murderers.

Rather than working toward constructive solutions when they feel they have fallen short, these men turn their rage outward. “It is a recourse; it’s a way for someone to perform [his] masculinity by engaging in this massive act of violence,” Madfis said.

Another common trait among mass killers is that they tend to blame others for their problems. “And part of that relates to masculinity, as well, because men are much more likely to externalize blame in general; they’re much more likely to see other people as causing them problems and to act,” Madfis said.

The correlation between masculinity and homicide goes beyond mass shootings. Almost 90% of suspects arrested for any form of homicide in California in 2018 were male, a disparity that has not changed much over the decades, even as the number of homicides declined. FBI data reflect the same discrepancy nationwide.

Dr. Garen Wintemute, an emergency medicine specialist at UC Davis Medical Center and director of the center’s Violence Prevention Research Program, said myriad factors might explain why men are more likely to kill than women, including learned behavior and genetic predispositions.

“Risk-taking behavior is more common among men than among women,” he said. “So, men binge-drink more often than women do and drink heavily on a chronic basis more often than women do. And alcohol abuse is a risk factor for violence.”

Handgun buyers with drunk driving convictions on their records were more likely to go on to be arrested for a violent crime than were buyers with clean records.

He also notes that when it comes to men who commit mass violence, increasingly “there’s been evidence of specific animosity toward women.”

Caroline Heldman is a professor of politics at Occidental College, a senior research advisor for the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media and executive director of the Representation Project, a nonprofit started by Jennifer Siebel Newsom, the governor’s spouse, that is devoted to challenging gender stereotypes.

Heldman said efforts to reduce mass shootings should emphasize reducing what is often termed “toxic masculinity,” the pernicious societal norm that being a man means “you can’t show emotion, that you can’t seek help when you need it, essentially that you can’t be fully human, you can’t be vulnerable.”

Encouraging media portrayals that depict boys and men in a vulnerable and realistic way could help reduce mass shootings, she said. Parents can help by examining the ways in which they discourage boys from healthy expressions of emotion.

“We know from studies that even feminist mothers will give girls, their daughters, more sympathy when they are hurt than their sons, which encourages boys to hide their pain and to deprioritize their pain, and view it as not being something that they can show the world,” Heldman said.

Madfis said mental health professionals also could play a role in preventing violent behavior by considering their patients’ conceptions of masculinity during counseling.

“Try to address mental health from a perspective that actually addresses men as men,” he said. “Try to grapple with healthy forms of masculinity, and try to reject the more toxic and problematic forms of masculinity.”

Phillip Reese is a data reporting specialist and an assistant professor of journalism at Cal State Sacramento. He writes for Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

This story was first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.