Max Tuerk’s parents view football differently after learning son had CTE

- Share via

They were once like everyone else, gathering with family members and friends to watch the most-viewed sporting event in this country.

They were a football family, their son a standout offensive lineman at USC who went on to play in the NFL.

That was before.

Before their son’s mental health deteriorated. Before their son’s death. Before they received evidence of what football did to their son’s brain.

The Super Bowl will be played Sunday and the parents of the late Max Tuerk won’t be watching.

“Absolutely not,” said Greg Tuerk, Max’s father.

Tuerk collapsed and died June 20, Father’s Day weekend, while hiking on the Bell View trail in Los Pinos Peak in Orange County.

Max died on a hike in June 2020, an autopsy later revealing his heart was enlarged. The Trabuco Canyon native was 26.

The aversion to football shared by Greg and his wife Val has an earlier origin, the years in which their oldest son was beset by mental health troubles.

After Max’s death, Greg and Val sent their son’s brain to the Veteran Affairs-Boston University-Concussion Legacy Foundation Brain Bank.

Researchers there studied Max’s brain and confirmed Greg’s and Val’s longstanding suspicions. The diagnosis: Stage 1 chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

“It didn’t make it any easier or better, but it did provide some understanding for how things changed so dramatically, for him to go from achieving his dream and being on the top of his game to [how] he kind of lost it all,” Val said.

Determined to honor the memory of their late son, the Tuerks have joined the Concussion Legacy Foundation in its Flag Football Under 14 campaign, which discourages children from playing tackle football before high school.

“You have to understand, we had fun with this whole thing too,” Greg said. “I’m not pretending like we didn’t enjoy the ride. We just didn’t really understand it.”

The probability of developing the degenerative brain disease CTE can be linked to the amount of tackle football played. In a 2019 study of 266 deceased former football players, VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank researchers found the likelihood increased by 30% for every year played.

Max started playing tackle football when he was in the fourth grade.

His parents didn’t think anything of it. Greg was also in the fourth grade when he started playing.

Max was a nationally-ranked prospect at Santa Margarita High. He was the first freshman to start at left tackle for USC. He was drafted by the Chargers in the third round of the 2016 draft.

He made the Chargers’ roster but didn’t play a single game in his rookie season. He served a four-game suspension the following year for violating the NFL’s policy on performance-enhancing substances, after which he was released by the Chargers. He was picked up by the Arizona Cardinals, for whom he appeared in one game in 2017. He was out of football by 2018.

Greg and Val said they noticed something was wrong with their son shortly after he was drafted.

“I’m over the game, man. I’m more thinking about the people behind it now. When you see these people and the hits that they’re taking on TV and I just think, ‘It’s not if, it’s when.’”

— Greg Tuerk, Max Tuerk’s father, on football

“His personality changed completely,” Val said.

“He became very paranoid,” Greg said. “He actually became delusional.”

Greg recalled a time when Max was playing for the Chargers and drove to Orange Country for a visit. Max told him the Russians were unloading nuclear weapons at the shut down San Onofre nuclear power plant near San Clemente.

“I was scared to death,” Greg said.

The problems worsened over the years. Max returned to Trabuco Canyon to live with his parents after his career ended and battled mental health issues over the remainder of his life.

“We were prouder of him for facing what he dealt with in those few years than we were for all of his football achievements,” Val said. “Because, man, that is a hard road to face. He accepted that he had to get treatment for the mental health issues, and he was fighting it with characteristic Max strength.”

Max collapsed while hiking with his parents on the Bell View trail in Los Pinos Peak in Orange County on Father’s Day weekend. The cause of death was unrelated to his mental health problems.

Watching their son struggle changed how Greg and Val view football.

“I can barely watch a football game right now,” Greg said. “I’m over the game, man. I’m more thinking about the people behind it now. When you see these people and the hits that they’re taking on TV and I just think, ‘It’s not if, it’s when.’ ”

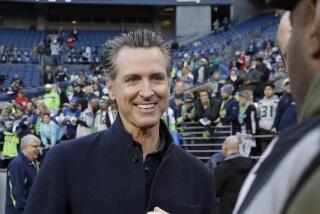

Greg pointed to Max’s former USC teammate, Chad Wheeler, who played for the Seattle Seahawks. Wheeler retired from football last year after he was arrested on domestic violence charges.

Greg wonders how football affected him.

At the same time, Greg can appreciate the arguments for how the sport can enhance lives.

“Believe me, I understand there were a lot of really positive things about football,” Greg said. “It teaches teamwork, it teaches you how to listen to a coach, it teaches you how to sacrifice for the greater good of the team. And it teaches you how to be tough physically and mentally. I would say there are better ways to do it.

“If he wants to play football in high school, he’s going to play football in high school. God bless him, good luck to you, go at it. In the meantime, go play flag football.”

A former all-conference defensive tackle at Harvard, CLF co-founder and chief executive Chris Nowinski is familiar with the lessons football can impart. However, Nowinski said, “Hitting kids in the head is not teaching them character. You can teach kids without them taking 500 head impacts a year.”

Former Santa Margarita coach Harry Welch honors lineman Max Tuerk, who died Saturday at 26.

An NFL spokesman didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

The league has spent more than $100 million recruiting children to play tackle football, according to the CLF, which cited official funding announcements by the NFL.

Nowinski is encouraged by a shift in public sentiment. The CLF will release the results Monday of a new national poll it conducted in collaboration with the Samford University Center for Sports Analytics. Of the 1,311 Americans surveyed, 77% supported state bans on tackle football for children younger than 12; 71% said it was inappropriate for the NFL to recruit children to play tackle football.

These are more than numbers to the Tuerks.

“We have a pretty unique perspective, unfortunately,” Val said.

So, they won’t be attending any Super Bowl parties, and they don’t expect the sport to be a part of their future.

If, or when, Max’s three siblings become parents, Val can’t imagine any of them allowing their children to play football.

“They’re devastated by the loss of their brother,” she said. “I would bet a million dollars there will be no football in our family.”

Kevin Ellison was known for hard hits while playing for USC and the Chargers. Did that lead to increasingly bizarre behavior before his death?

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.