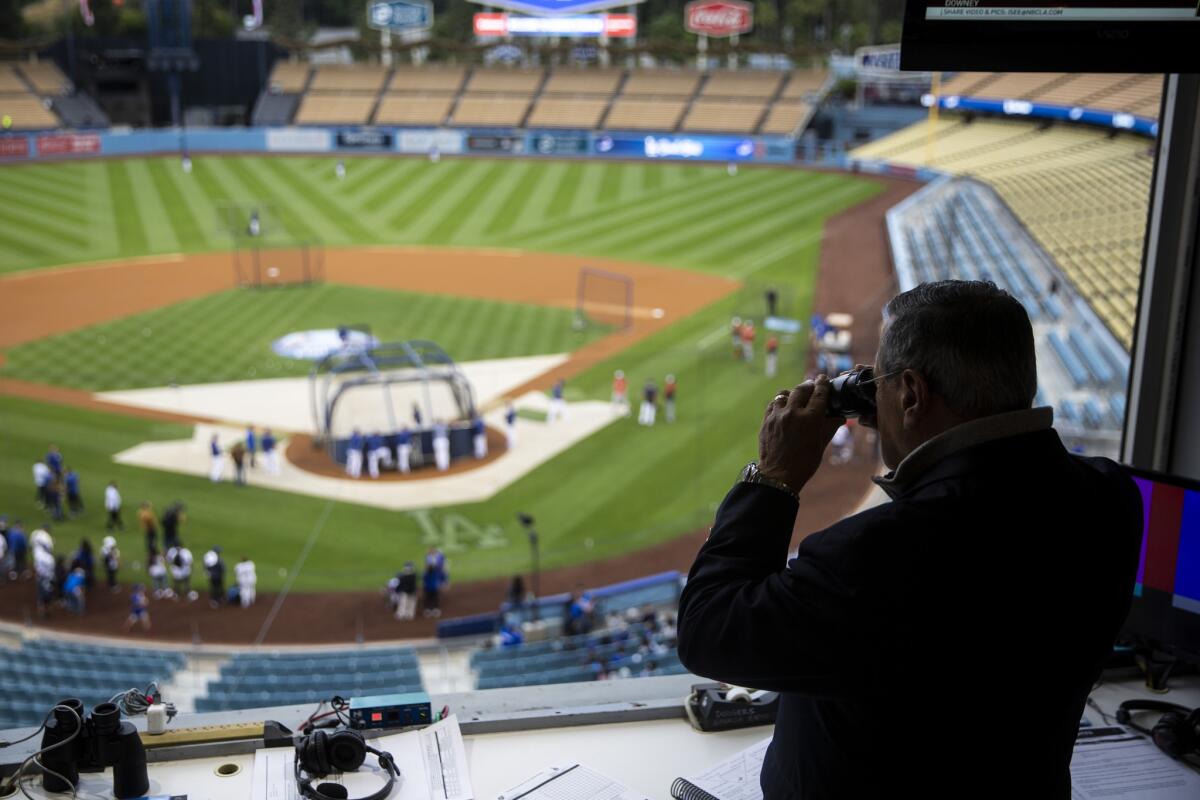

Column: Jaime Jarrin’s return to Dodgers’ broadcasts eases pain of wife’s passing

Jaime Jarrin, the Spanish-language radio play-by-play broadcaster for the Dodgers, shares memories of his wife, Blanca, who died Feb. 28.

- Share via

He was cutting back. He was staying home. He missed his wife.

This winter, before his 61st season as a Dodgers Spanish-language broadcaster, Hall of Famer Jaime Jarrin decided he would no longer travel to road games outside of the National League West because he had a more important calling in San Marino.

Her name was Blanca. They had been married 65 years. She was the one who picked out his trademark elegant clothes. She was the one he phoned four times a day. She was the one who waited up for him at home, sitting in her caramel leather recliner in the darkness, after every game, every night, every trip.

Blanca was his best friend, and he was tired of living through so many sweet summer evenings without her, so he informed the Dodgers he would be spending the homestretch of his life with his love.

“She deserves it, I deserve it,’’ Jaime said in February, mapping out a gloriously slow walk into forever.

They didn’t even make it to opening day.

In an Arizona hotel room early in spring training, despite her husband’s frantic efforts to save her, Blanca Jarrin lost consciousness in a chair and died from a heart attack at age 85.

One minute, Jaime was slipping his wife’s fashionable shoes on her feet for a quick trip to the hospital. The next minute, he was carrying her ashes in an urn in the front seat of a car headed for uncertainty.

“It wasn’t supposed to happen like this,’’ said Jaime, 84. “It seems so unfair.’’

Shortly after her death he received a phone call from Vin Scully, who understood the pain of losing a wife. Scully gave him some advice that confirmed Jaime’s instincts. He knew what he had to do.

Jaime phoned the Dodgers and asked if he could return to the booth and go back on the road full time. They said yes before he could finish the sentence.

“When I’m doing a ballgame, it’s the only time I feel normal,’’ he said. “I will now carry Blanca’s spirit with me, to every city, every game, in the seat right next to me.’’

So he has, bravely, powerfully, rolling out his lyrical “Se va, se va, se va’’ calls across the KNTQ-AM 1020 airwaves every night, in every city, with no acknowledgement of this Dodger season’s one true thing.

Nobody on the field is playing in more pain than the man behind the microphone.

“She didn’t really like baseball, but Blanca would sit home and listen to every game,’’ said Jaime, his elegant voice dropping to a whisper. “She would listen because it was me.’’

::

They met in a Quito, Ecuador, radio station when they were teenagers. Jaime Jarrin remembers it exactly. It was a Saturday.

He was a hotshot young announcer. Blanca Mora was a member of a visiting high school choir.

“We caught each other’s eye,’’ Jaime said. “We knew.’’

They dated a year. They were married as kids. Blanca was 19, Jaime was 18. Two years later, she convinced Jaime to come to Los Angeles and seek his broadcasting fortune.

“She was always the one who pushed me,’’ Jaime said.

He initially came alone. He worked in a metal fence factory to raise the money to bring Blanca and son Jorge to join him. Once Blanca arrived, she settled into life as a mother and homemaker while Jaime broke into the local radio scene and eventually made his debut on the Dodgers’ landmark Spanish-language broadcast team in 1959.

“Blanca never worked outside the home,’’ said Jaime. “But she was always working.’’

While she held no formal job, Blanca performed the 24-hour job of raising the family while Jaime spent much of the summer in ballparks across the country. While her husband was living in the spotlight, she was on the hard bleachers at a youth soccer game. While he was interpreting for Fernando Valenzuela during Fernandomania, she was storming grade schools to confer with teachers.

“My mom did the incredible job of making sure we always felt the presence of a mother and father,’’ said Jorge, the oldest son who is fighting through his grief to work the Dodger broadcasts with his dad, a job he has held for four years. “We never lacked for anything.’’

As Jaime was attracting legions of Latino fans to Dodger Stadium, Blanca was at home making sure her children never forget their heritage.

“We would read Spanish aloud from a book for an hour every night so we would never lose the language,’’ Jorge said. “She would tell us, because of who you are, in this country you have to work a little bit harder than everyone else.’’

Through all the years, nothing worked as well as the marriage. Jaime and Blanca not only celebrated his many successes together, but grieved with each other at the death of son Jimmy from a brain aneurysm in 1988.

“She didn’t like the spotlight, she was always walking a step behind me,’’ Jaime said. “But she was the one who carried me.’’

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

They would hold hands in restaurants between courses. They would laugh together at anything. They were equally happy taking exotic cruises or sitting at home watching telenovelas.

When they were out together, Blanca couldn’t help but share their good fortune. She carried around an envelope with $20 bills and a purse full of Dodgers tickets. She would spread her riches to waiters, busboys, valets, anybody who showed them kindness. She once gave an $80 tip to the garbage worker pulling their cans from the curb to the back of the house.

“I was like, ‘Blanca, that’s a pretty big tip for someone pulling your cans,’’’ Jaime recalled with a laugh. “She said, ‘Jaime, that man is here every week with a kind word and a smile, and that money will mean a lot more to him than it does to us.’’

Doesn’t Blanca sound like somebody you’d like to hang out with? Jaime thought so, and he hated leaving home, and this led to a tradition when he was on the road. No matter where the Dodgers were playing, he would call Blanca at 10 a.m. Pacific time. That would be only the first of four calls a day. He would touch base with her before games, after games, late at night, whenever, wherever.

“I just liked to hear her voice,’’ he said.

This year their summer separation was finally going to end. They were going to have more adventures. They decided to start early. Shortly after the beginning of spring training, there was a break in his schedule, so they decided to drive from Glendale, Ariz., to Santa Fe, N.M., because Blanca always loved Santa Fe.

They stopped in Flagstaff on the way. Blanca woke up in their hotel room at 5:30 a.m. in distress. She sat in a chair and Jaime prepared to take her to the hospital when she suddenly lost consciousness. An ambulance was summoned. Jaime attempted resuscitation for a few minutes before the paramedics arrived and rushed her to the hospital, where she was pronounced dead at 8:32 a.m. on Feb. 28.

“I try to understand that this is the design of life,’’ Jaime said. “But it is so hard to understand.’’

Several days later, Jaime was on the phone with Lon Rosen, the Dodgers executive vice president and marketing boss.

“He said, ‘I want to talk to you about something,’’ Rosen said. “I said, ‘I know what you’re going to say, you want to go back to working the whole season, right? Done. No need to even ask.’”

Rosen added, “Jaime is the Fernando Valenzuela and Sandy Koufax of Dodger broadcasts. He can always come back from a partial retirement.’’

He made his return at a spring training game in early March. He opened the broadcast by telling the listeners what had happened. He has not spoken about it since.

He and Jorge, who routinely fills in for his father during the middle three innings, have forged ahead through their common pain.

Jaime talks about dreams of Blanca in which he cannot see her face. Jorge relates dreams about talking to his mom on the phone, but he cannot hear her voice. Jorge travels with his father when the Dodgers are on the road. His brother Mauricio stays at the house when the Dodgers are at home. He still fights the feeling that he is very much alone.

“It’s still like a dream, you think you’ll turn around and she’ll be coming there,’’ Jaime said. “You have to realize that she is not there.’’

Together the father and son have also taken comfort in establishing the Jaime and Blanca Jarrin Foundation to provide financial aid for students interested in law or journalism.

Jaime has also taken some advice from Pepe Yniguez, the Dodgers Spanish-language television broadcaster who lost his wife Margarita to cancer in 2006. Every day before coming to Dodger Stadium, Yniguez visits the resting place of his late wife at Rose Hills Memorial Park.

“Trying to survive, it’s very hard, but you have to do it,’’ Yniguez said. “Jaime is a strong man, and doing the games is good for him, because the game is like giving us a shot so we won’t feel the pain.’’

Then the games end, the trips end, like on a recent night when the team returned from St. Louis. It was Jaime’s first trip since Blanca’s death. He walked into the house and walked up the stairs to their bedroom and the caramel leather recliner was empty.

“I started crying, because that’s when I knew,’’ he said, tears welling up again. “For more than 50 years, she’s been waiting for me in that chair.’’

That night Jaime Jarrin somehow found sleep, and the next day he somehow found his way back to Dodger Stadium for another game, dressed in a fine suit Blanca would have approved of, greeting folks with Blanca’s generous spirit, making room in the booth for one more.

Get more of Bill Plaschke’s work and follow him on Twitter @BillPlaschke

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.