Dodgers Dugout: Farewell, Maury Wills

- Share via

Hi, and welcome to another edition of Dodgers Dugout. My name is Houston Mitchell, and this issue is dedicated to Maury Wills. We will return to our regular Dodgers coverage Tuesday.

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Maury Wills, who almost single-handedly brought the stolen base back to prominence in baseball, died Tuesday at his home in Sedona, Ariz. He was 89.

Making the news even sadder is that the Hall of Fame Golden Days Era voting committee did not vote him into the Hall of Fame last year, when he would have been around to enjoy it. I think Wills eventually gets in, and his family will be able to appreciate it, but not Wills.

And he ought to be in. And the Dodgers should have retired his number. I always have felt the Dodgers should be more like the Yankees in this regard, retiring numbers of players who were team legends even if they aren’t Hall of Famers. And I’d make Wills and Fernando Valenzuela the first to be honored that way.

Enjoying this newsletter?

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a Los Angeles Times subscriber.

But enough about that. Let’s celebrate Wills’ incredible life.

Wills was born Maurice Morning Wills on Oct. 2, 1932, in Washington, D.C. He was one of the 13 children of Guy Wills, born in 1900, and Mable Wills, born in 1902.

Wills starred in football and baseball in high school, and signed with the Dodgers in 1950. The family was hoping for a big signing bonus. Instead, the offer was a new suit for Maury, though the family eventually squeezed $500 out of the Dodgers.

Wills was assigned to Class D Hornell in New York and began his stint in the minor leagues. It continued through 1951. And 1952. And 1953. And 1954. And 1955. And 1956. And 1957. And 1958. He wasn’t the best hitter in history, but when he reached triple-A Spokane in 1958, manager Bobby Bragan decided to make him a switch-hitter to take advantage of his speed.

In his book, “It Pays to Steal,” Wills wrote, “He took a big interest in me and just being around him made my baseball life worth living. I had just about given up on myself. When he asked me to switch-hit, I said, ‘Bobby, I’ll try anything once.’ ”

Wills struggled a bit in 1958 while learning to switch-hit, finishing with a .253 batting average. In the spring of 1959, the Dodgers sold his contract to the Detroit Tigers. After a few spring training games, the Tigers sent him back to the Dodgers, who again assigned him to triple-A.

Then Wills got a lucky break. Pee Wee Reese had retired before the 1959 season, and Don Zimmer was the Dodgers’ starting shortstop. In June, Zimmer broke a toe. Bragan told the Dodgers it was time to give Wills, who was hitting .313, a shot. Zimmer never got the job back. Wills hit .260 with seven steals and played solid defense as the Dodgers won the NL pennant and faced the Chicago White Sox in the World Series. Wills played in all six games and hit .250 with a steal as the Dodgers won the title.

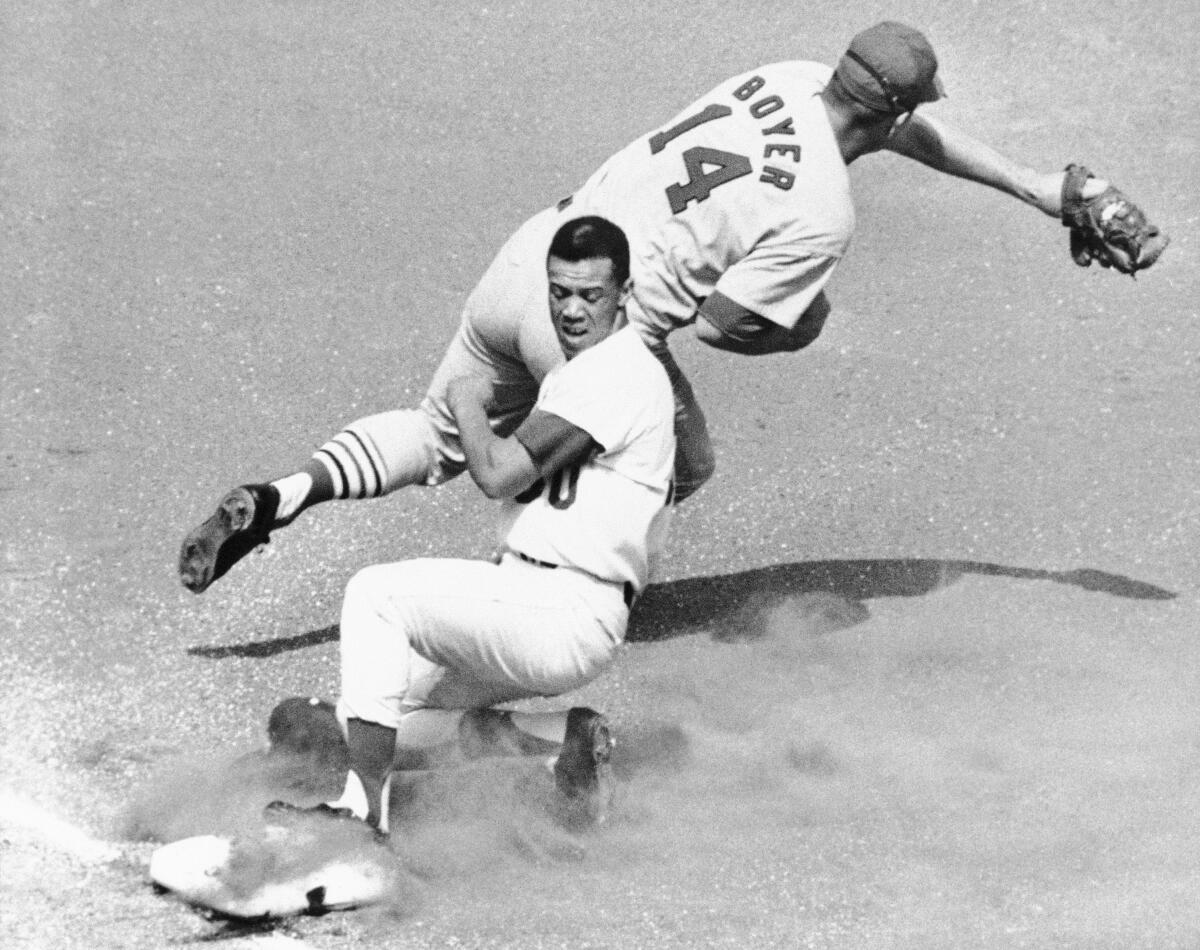

That set the stage for a long Dodgers career, as Wills led the NL in stolen bases from 1960 to 1965, including a then-record-setting 104 in 1962, when Wills won the MVP award. He played in every one of the Dodgers’ 165 regular-season games that year (the Dodgers lost a three-game playoff against the Giants), a record for games in a season that will probably never be broken. As the Dodgers got deeper into the season, the wear-and-tear took a toll on Wills’ body, as his legs and sides were bruised from all of the hard sliding.

“His body is so bruised he constantly looks as if he had just crawled out of a plane wreck,” Times columnist Jim Murray wrote. In his book, Wills wrote, “Do I think I’ll ever steal 104 bases again? No, I can’t believe I did it to this day. I don’t see how I can ever come close again. The physical beating I took is more than I want to endure.”

In 1963, he stole 40 bases and hit .302. The Dodgers swept the Yankees in the World Series, with Wills going two for 15.

In 1964, he stole 53 bases. In 1965, 94. That was the last time he led the league.

From 1960 to ‘65, here are the majors’ stolen base leaders:

Wills, 376

Luis Aparicio, 258

Lou Brock, 146

Willie Davis, 139

Vada Pinson, 137

Henry Aaron, 129

Frank Robinson, 115

Chuck Hinton, 109

Dick Howser, 102

No one else stole at least 100 bases in that span.

From 1966 to ‘70, 14 players stole at least 100 bases. From 1971 to ‘75, 22 players did it.

After winning the 1965 World Series against the Minnesota Twins (Wills hit .367 with three steals), the Dodgers were swept in embarrassing fashion by the Baltimore Orioles in the 1966 World Series. Wills went one for 13 in the postseason but had stolen 38 bases during the season and said his right knee really hurt.

Team owner Walter O’Malley sent his team on a tour of Japan after the World Series. Wills didn’t want to go, O’Malley said he had to. Wills played a couple of games, then asked for permission to fly back to L.A. to have a doctor look at his knee. His request was denied. He flew back anyway. But first he stopped in Hawaii for a week and appeared on stage at a couple of shows by Don Ho. O’Malley wasn’t pleased and wanted Wills traded.

On Dec. 1, 1966, the Dodgers sent Wills to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Bob Bailey and Gene Michael. The Montreal Expos took him in the expansion draft and began their first (1969) season with Wills as the starting shortstop. He hated Montreal and walked off the team for a little while. After coming back, the Expos sent him to the Dodgers along with Manny Mota for Ron Fairly and Paul Popovich. After hitting .222 with the Expos, Wills rebounded and hit .297 with 25 steals for L.A.

Wills last season was 1972, when he hit only .129 in 72 games. The Dodgers released him after the season.

After his release, Wills told Ross Newhan of The Times, “These things happen. I’ve had a fine career. I’m happy to have been a Dodger. I simply believe that 1972 was not a true indication of what I can still do if I am in shape and active.”

Wills became a broadcaster until the end of the 1980 season, when the Seattle Mariners hired him as manager. It was disastrous. Wills would call for relievers who hadn’t warmed up. In April 1981, he was suspended for two games after ordering the grounds crew to enlarge the batter’s boxes at the Kingdome making it a foot closer to the mound. Wills ordered it because the game before, Oakland manager Billy Martin complained that Seattle’s Tom Paciorek repeatedly stepped out of the batter’s box while hitting. Martin noticed the batter’s box was bigger before the next game and had the umpires measure it.

Wills was fired soon after and ended his managerial career with a 26-56 record.

Wills spent the next few years dealing with drug and alcohol issues. David Shaw of The Times wrote in 1991 that Wills “spent more than $1 million on cocaine, sometimes, staying high for 10 days at a time, locking himself in his home alone for months.”

Finally, Wills entered a substance abuse program after an intervention by former teammates Tommy Davis and Don Newcombe. He became a valued spring training coach for the team, teaching baserunning and stealing fundamentals to whoever was smart enough to listen, including a young Dave Roberts. Roberts wears No. 30 to honor Wills.

“He just loved the game of baseball, loved working and loved the relationship with players,” Roberts said. “We spent a lot of time together. He showed me how to appreciate my craft and what it is to be a big leaguer. He just loved to teach. So I think a lot of where I get my excitement, my passion and my love for the players is from Maury.

“And in a strange way, I think I enriched his post-baseball career as far as watching every game I played or managed. I remember even during games I played, he’d come down from the suite and tell me I need to bunt more, I need to do this or that. ... A coach would say, ‘Maury is at the end of the dugout and wants to talk to you.’

“It just showed that he was in it with me, and to this day, he would be there cheering for me.”

Just like fans cheered “Go Maury Go” many years ago.

Maury Wills answered your questions

In Sept. 2021, Wills answered questions posed by readers of this newsletter. His answers are reprinted below:

Ray Pacini of Newport Beach asks: Who was the toughest pitcher to hit and who was the toughest pitcher to steal off of?

Wills: I guess Larry Jackson. He’s the answer to both. If I got a hit or stole a base, then the next time up he made me skip rope or feel the consequences some other way. (Editor’s note: Wills was 36 for 136 against Jackson, with two extra-base hits and three walks).

Michael Ward of Santa Barbara asks: Who was the easiest pitcher to steal on?

Wills: Most of them, really!

Glen Riley asks: How important was it for you to have Jim Gilliam hitting behind you?

Wills: Very important. He took pitches for me, he watched pitches go by [that] he could hit in order to give me a chance to steal. He knew how to block catchers without being called for interference. And he never complained about doing all this. He would do anything it took to help the team win, even if it meant sacrificing personal glory.

Marc Josloff of Freeport, N.Y., asks: How do you make peace with the fact that you haven’t been voted in to the Hall of Fame to this point?

Wills: I don’t think about it. I’m just grateful that I’m still here and when I look back at my career I have a little chuckle.

Don Wanlass asks: What was the best Dodger team you played on?

Wills: I never look at it that way. I enjoyed every Dodgers team I played on. They were all good. I remember playing in the Coliseum in front of 90,000 people. Before that, the biggest crowd I played for was 1,500. Imagine the sound of 90,000 people saying “Go, Maury, go.” I knew I had a home.

Dozens of people asked: What did you think when the Giants watered down the basepath between first and second to keep you from stealing?

Wills: I was flattered that they would go through all that trouble to try to stop me. Base stealing is another sport all by itself. A game within a game. I was the mouse and the cats were trying to get me.

The speech Wills wanted to give

The Dodgers honored Wills at the stadium this year, but unfortunately he was unable to attend. Instead, he was kind enough to share, exclusively with Dodgers Dugout readers, the speech he would have given:

“For as far back as I can remember, I wanted to be a baseball player. I was playing sandlot baseball before I had a pair of shoes. Not cleats – shoes, period. And from the age of 14, when my hero, Jackie Robinson, became a Dodger, I wanted to be a Dodger. I spent nine years in the minor leagues waiting for that chance, and finally made it. So, like Lou Gehrig, I’m one of the luckiest guys in the world. I thank God for a lot of people in my life. I had wonderful parents, I have marvelous children and grandchildren. I wish I could name them all, but you’d be here all night, and you’d much rather watch the game. So, here are just a few:

“Jerry Priddy, who, when I was 11, was the first person to tell me that I had the talent to become a good ballplayer. (He also asked me why I was barefoot.)

“Rex Bowen and John Curry, who brought me into the Dodgers organization in the first place.

“Bobby Bragan, who taught me how to switch hit.

“Walter Alston, who encouraged me to steal bases.

“Fred Claire, and especially Don Newcombe, who saved my life by getting me into a rehab program.

“Sandy Koufax, Don Newcombe, Tommy Davis, John Roseboro, Willie Davis, Don Drysdale, Dave Roberts and John Boggs, for being such great friends.

“The Los Angeles Dodgers, who gave me not only my first chance but second, third, multiple chances at a great career.

“Dodgers fans, who encouraged me time and time again to give my all. On days when I was really hurting, hearing “Go! Go! Go, Maury, go!” kept me running.

“And last, but certainly not least, is my wonderful wife, Carla, who has brought me so much joy for the last 15 years.

“I wouldn’t be here today if my friends, with the help of God, and some wonderful organizations that want to remain anonymous, hadn’t literally saved my life. Please, if you know someone with a substance abuse problem, help them save their lives too.

“I wish for each of you to have as fortunate a life as I have had. God bless the Los Angeles Dodgers. And may God bless you all.”

Up next

Tonight: St. Louis (*Jose Quintana, 5-6, 3.16 ERA) at Dodgers (TBD), 7 p.m., SportsNet LA, AM 570, KTNQ 1020

Saturday: St. Louis (*Jordan Montgomery, 8-5, 3.26 ERA) at Dodgers (TBD), 6 p.m., SportsNet LA, AM 570, KTNQ 1020

Sunday: St. Louis (Adam Wainwright, 11-9, 3.29 ERA) at Dodgers (TBD), 1 p.m., SportsNet LA, AM 570, KTNQ 1020

*-left-handed

Stories you might have missed

Plaschke: Maury Wills stole Dodger fans’ hearts. Changed the game. Not enough for Hall of Fame

Maury Wills, legendary base stealer for Dodgers, dies at 89

And finally

Maury Wills instructs at spring training. Watch and listen here.

Until next time...

Have a comment or something you’d like to see in a future Dodgers newsletter? Email me at houston.mitchell@latimes.com, and follow me on Twitter at @latimeshouston. To get this newsletter in your inbox, click here.

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.