- Share via

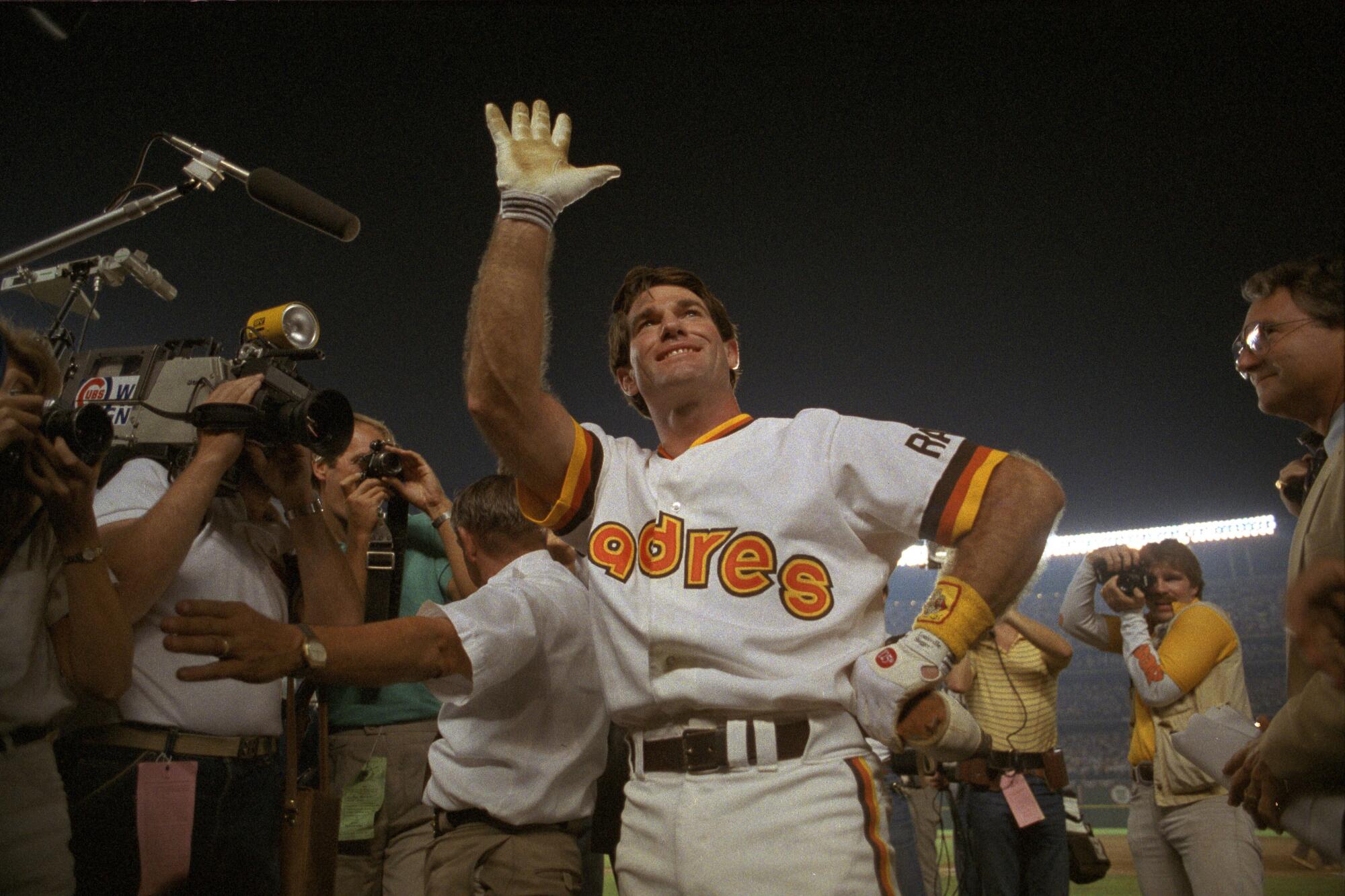

Steve Garvey couldn’t help but notice the futuristic metal cubes. They ringed the presidential desk of McDonald’s owner Ray Kroc, who had invited the Dodgers star to his hilltop home in La Jolla in hopes of convincing him to join his San Diego Padres. It was 1982, Time magazine had named the personal computer its Machine of the Year, and to Garvey, the glowing devices and their mystifying connection to the world at large was something out of “Blade Runner,” which captivated audiences that summer.

“They looked like small black-and-white TV screens,” recalled Garvey, so transfixed at the time that he walked around to Kroc’s side of the desk to get a better view. “He told me he was minding the store, checking sales in North America and Europe. He was in his 80s, sitting there in his little golf cap, making the first big move in the history of the Padres organization, and he liked big moves.”

Small screens, big vision. The guy who sold cheeseburgers for 19 cents and fries for a dime understood the monumental value of landing Garvey, the personification of Dodger Blue. Kroc dreamed of being an arch rival in the truest definition.

“He said, `‘Stevie’ — and you know those were different days when somebody calls you Stevie — ‘we really want you here, son,’” recalled Garvey, who signed a five-year deal for a then-robust $6.6 million. “He told me, ‘I know what you can do on the field, but off the field is really where you can make a difference here.’ He paused and said, `I’ve got a problem. I can only pay you in Big Macs and French fries.’

A slightly better throw to first might have delivered a no-hitter to Trevor Bauer in his first start in Chavez Ravine as a Dodger.

“I told him, ‘Well, can I have them for a lifetime? Because that’s a good place to start.’ He loved the banter.”

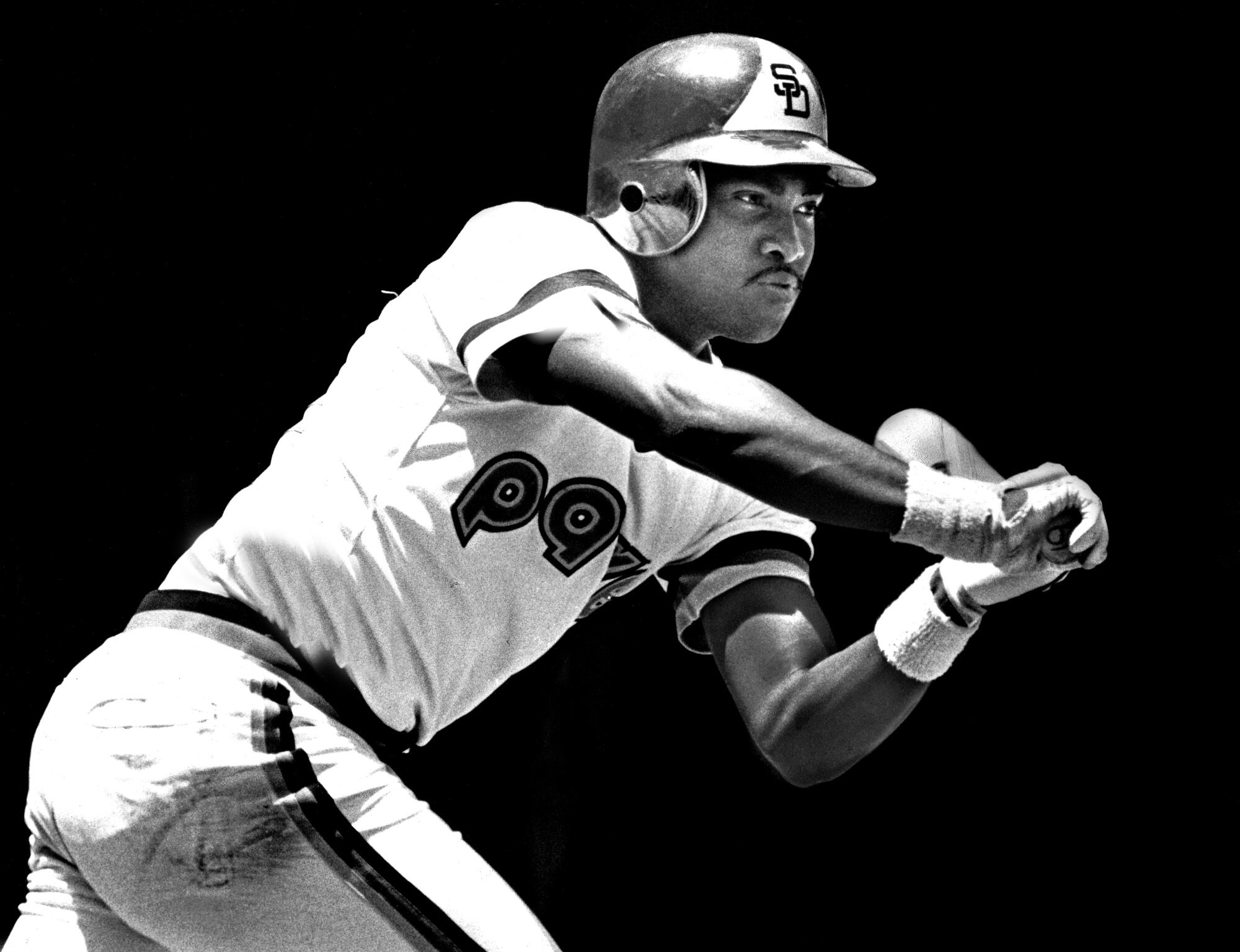

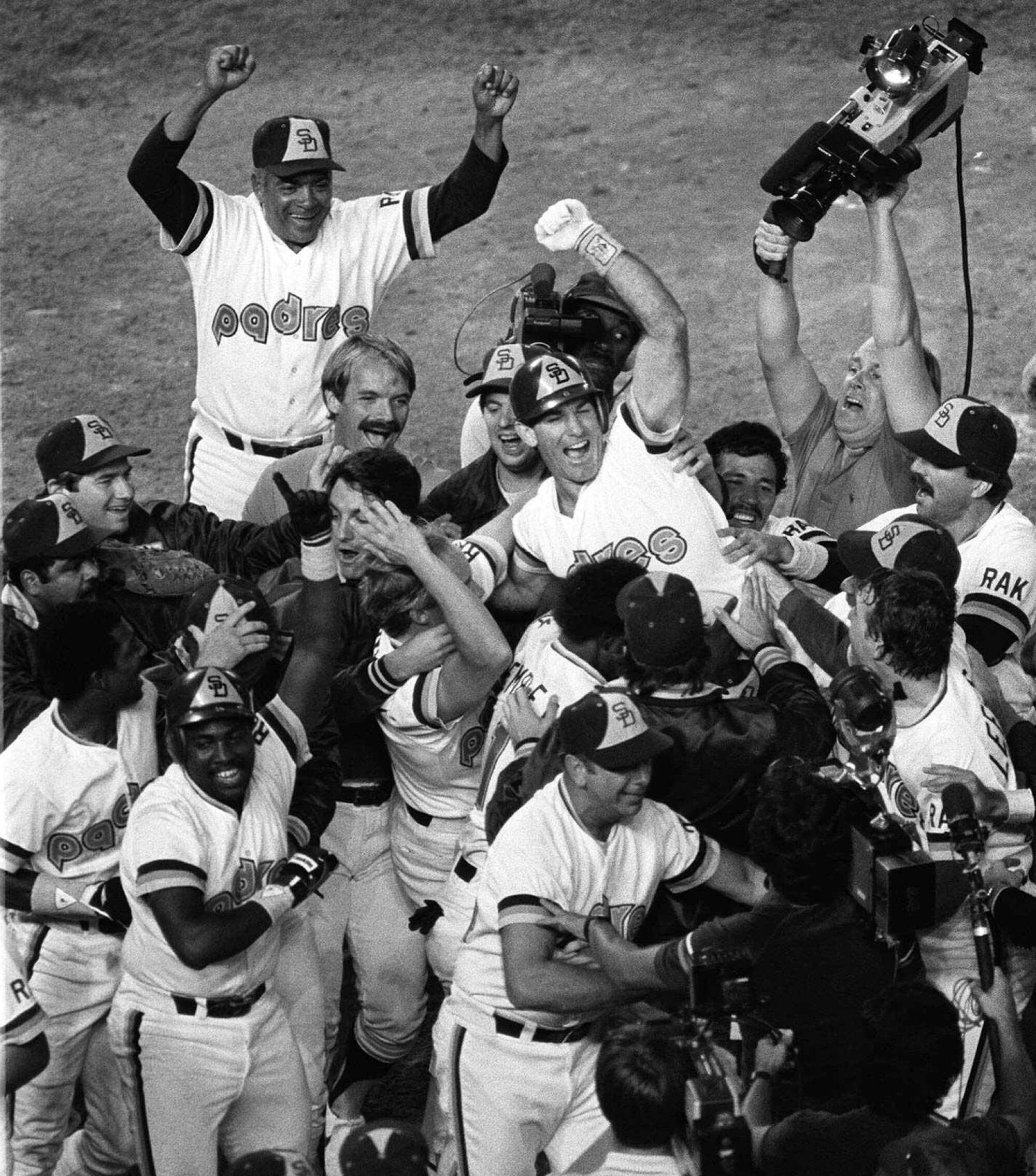

Kroc died in January 1984, so he wasn’t around to see his beloved Padres reach the World Series later that year with a team composed of such seasoned talent as Garvey, closer Rich “Goose” Gossage, third baseman Graig Nettles, and shortstop Garry Templeton, and rising stars in right fielder Tony Gwynn, pitcher Eric Show, and base-stealing burner Alan Wiggins.

Mr. Golden Arches missed Garvey hitting a walk-off home run against the Chicago Cubs in the 1984 National League Championship Series, regarded by many as the greatest moment in San Diego sports history. Kroc would have loved how the Cubs had the celebratory champagne on ice, only to grudgingly sell it to the Padres for half price. He wouldn’t see his club eventually retire Garvey’s number.

“I brought the Dodger way to do things,” said Garvey, 72, who still has Ken-doll hair and Popeye forearms. “How we won, how to close out games, how to close out seasons.”

Four decades later, with San Diego still pursuing its first World Series title, the electrifying Padres have wrestled the spotlight away from Los Angeles, even as the Dodgers are coming off their first World Series title in 32 years. While the Dodgers have the corporate veneer of baseball’s IBM, the Padres — fueled by stars Manny Machado and Fernando Tatis Jr., both of Dominican descent — embody the brash, ambitious, convention-bucking strut of a software startup.

“When I got signed, I remember telling the scout who signed me, when I get out of this game, I would like to be remembered almost like a Dominican Derek Jeter,” Tatis said in August. “All of the respect he had in the game, all of the World Series he won, all the history he added to this game. I would love to see myself as that.”

The Times’ Jorge Castillo and San Diego Union Tribune’s Kevin Acee compare notes ahead of the first of 19 games between the NL West division rivals.

Whereas the Dodgers cherish the history of their classic blue-and-white uniforms, the bat-flipping Padres scoff, “OK, Boomer,” and don their retro brown and yellowish gold, sort of a California Mission statement. With their outsized celebrations and constant dugout chatter, the youthful Padres don’t chase what’s cool and current in baseball, they define it.

“I am very proud of the Padres,” said retired NBA star Bill Walton, who was born and reared in La Mesa and lives 1½ miles from Petco Park. “I’m proud of their history, I’m proud of their present, and I’m incredibly proud of the future. Everything is in place for success.”

Tony Gwynn Jr., whose late father was “Mr. Padre,” and among the most popular athletes in San Diego history, said the expectations for this team have been recalibrated. Still, there’s a difference between setting expectations and fulfilling them.

“From a fan’s standpoint, you always feel pretty good if the Padres can take the season series from the Dodgers,” said Gwynn, Padres color analyst for 97.3 The Fan and someone who played for both ballclubs. “At those times, you honestly knew there wasn’t anything after. There wasn’t something else you were shooting for.

“I don’t think that’s the case this year. Yes, it would be sweeter to take it to the Dodgers. But this season’s success will be marked by how deep they get into the postseason. Throughout the city there’s an expectation that not only should we be competing with the Dodgers, we should be looking to surpass them. That’s the temperature I gauge.”

The Padres, who began as an expansion team in 1969 and borrowed their name from the Pacific Coast League franchise founded in 1936, had a few great players come through in the early days — Dave Winfield, Rollie Fingers, Ozzie Smith — but struggled to get consistent traction. They finished in last place in each of their first six seasons, losing 100 games in four of those.

“When I was with the Dodgers, we’d go down there and for us it was almost like a three-day vacation,” Garvey said. “We’d stay at the Town and Country in Mission Valley, and invariably would lose the series. We didn’t take it that seriously early in the year. First couple times down there, they’d probably win the series. And then when it got serious, September, we’d go down and sweep ‘em and get ready for the playoffs.”

In a testament to their groping for an identity over the years, the Padres have had more than a dozen uniform changes, many of them dramatic, experimenting with brown and yellow, brown and orange, brown and yellow and orange, blue and orange, blue and white, blue and tan, and now brown and yellowish gold. They tried pinstripes and different shades of camouflage, too.

The uniforms were one of the issues Garvey addressed when Kroc signed him.

“I suggested yellow and brown never inspired anyone,” Garvey said. “So he let me redesign the uniforms. Ralph Lauren would have been proud of me.”

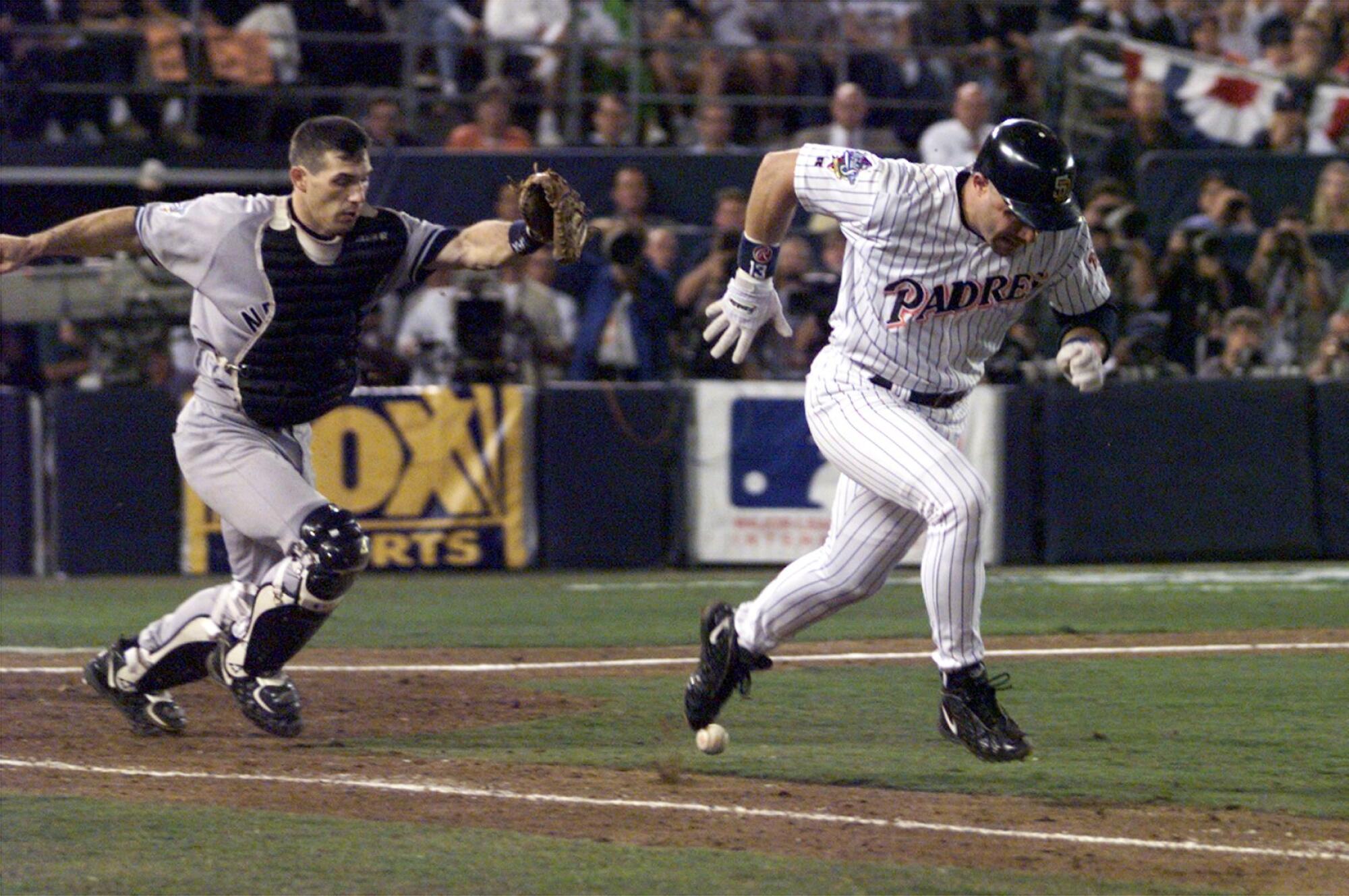

Of course, nothing looks as good as winning. Undeniably, there were flashes of excellence for the Padres, notably when they reached the World Series in 1984 against the Detroit Tigers and 1998 against the New York Yankees. But San Diego went 1-8 in those games. And as satisfying as it was to them in 1996, when the Padres swept L.A. on the final weekend of the season, erasing the Dodgers’ two-game lead and sending them limping into the playoffs as a wild-card team, that was but a fleeting moment.

“I would say this rivalry is in its infant stages. But there are certainly elements you can see that can make this thing a sustained rivalry.”

— Tony Gwynn Jr.

Thirty-nine years after Kroc made that historic Garvey signing, the Padres have a glaring unchecked item on their to-do list: They haven’t developed a serious rivalry with the Dodgers, and are still more of an annoyance than ogre to their neighbors to the north. The Dodgers and their fans are far more preoccupied with the San Francisco Giants.

“Rivalries are built around two teams that have had a sustained amount of success, usually in a close area,” said Gwynn, whose father spent his entire Hall of Fame career in San Diego.

“It just hasn’t worked out to where the Padres have been successful enough over a long period of time. So I think now what you have is a budding rivalry. I would say this rivalry is in its infant stages. But there are certainly elements you can see that can make this thing a sustained rivalry.”

These days, the Dodgers can’t help but check their rear-view mirror. Yes, they’re coming off their seventh World Series victory, and have won the last eight division titles. But San Diego is on the ascent, having reached the postseason in 2020 for the first time in 13 seasons — although that playoff run was ended, naturally, by the Dodgers.

The Padres are spending money in ways that would have fried Kroc’s circuit board, in February finalizing a $340-million, 14-year contract for spectacular shortstop Tatis, the longest deal in baseball history. That came on the heels of a $300-million, 10-year deal for slugging third baseman Machado in 2019, and a $144-million, eight-year contract for first baseman Eric Hosmer in 2018.

“We love this city,” Padres majority owner Peter Seidler told the Associated Press hours after his team announced the deal for Tatis. “We want to honor the support our extraordinary fans give us.

“In 1984 and 1998, this place went crazy. And those were real teams that went to the World Series. I know we have the city’s trust and the city trusts us. We’re going to put good teams out there. From a franchise standpoint, we’re going to get support and we’re going to back it up with our actions reflective of the eighth-largest city in America.”

If anyone understands that looming blue dynasty in L.A., it’s Seidler. His grandfather, Walter O’Malley, brought the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles in 1958, and his uncle, Peter O’Malley, owned them until 1998.

Dodgers third baseman Justin Turner called the Padres’ offseason moves “exciting” and “good for baseball,” and likened the regular-season matchups with San Diego — of which there are seven in a 10-day stretch in April beginning Friday — to World Series-type games.

“I think he’s pretty spot on,” teammate Walker Buehler said. “Obviously, they’ve accumulated some talent over there, starting with Hosmer and those guys, and Machado. That’s great. I think it’s great for the game. We want good teams, we want really, really good teams, and I think they’re in that conversation.”

The two ballclubs have intersected in some awkward and amusing ways over the years. A memorable one was Tommy Lasorda’s unvarnished dressing down of Kurt Bevacqua in 1982, after the Padres infielder — angry that L.A. reliever Tom Niedenfuer had drilled San Diego’s Joe Lefebvre in the head — said the Dodgers manager should be fined for the beaning.

“You go down there and the attendants say hello and they’re nice, they help you. It’s easy to get food. It’s a positive family experience, really a wonderful place to see a game.”

— Dodgers fan Chris Rising on attending games at Petco Park in San Diego

Bevacqua referred to Lasorda as “the fat little Italian,” to which the manager responded with an R-rated tirade bluer than anything the Dodgers ever wore. An audio recording of the rant, set to still photos, has 1.2 million views on YouTube.

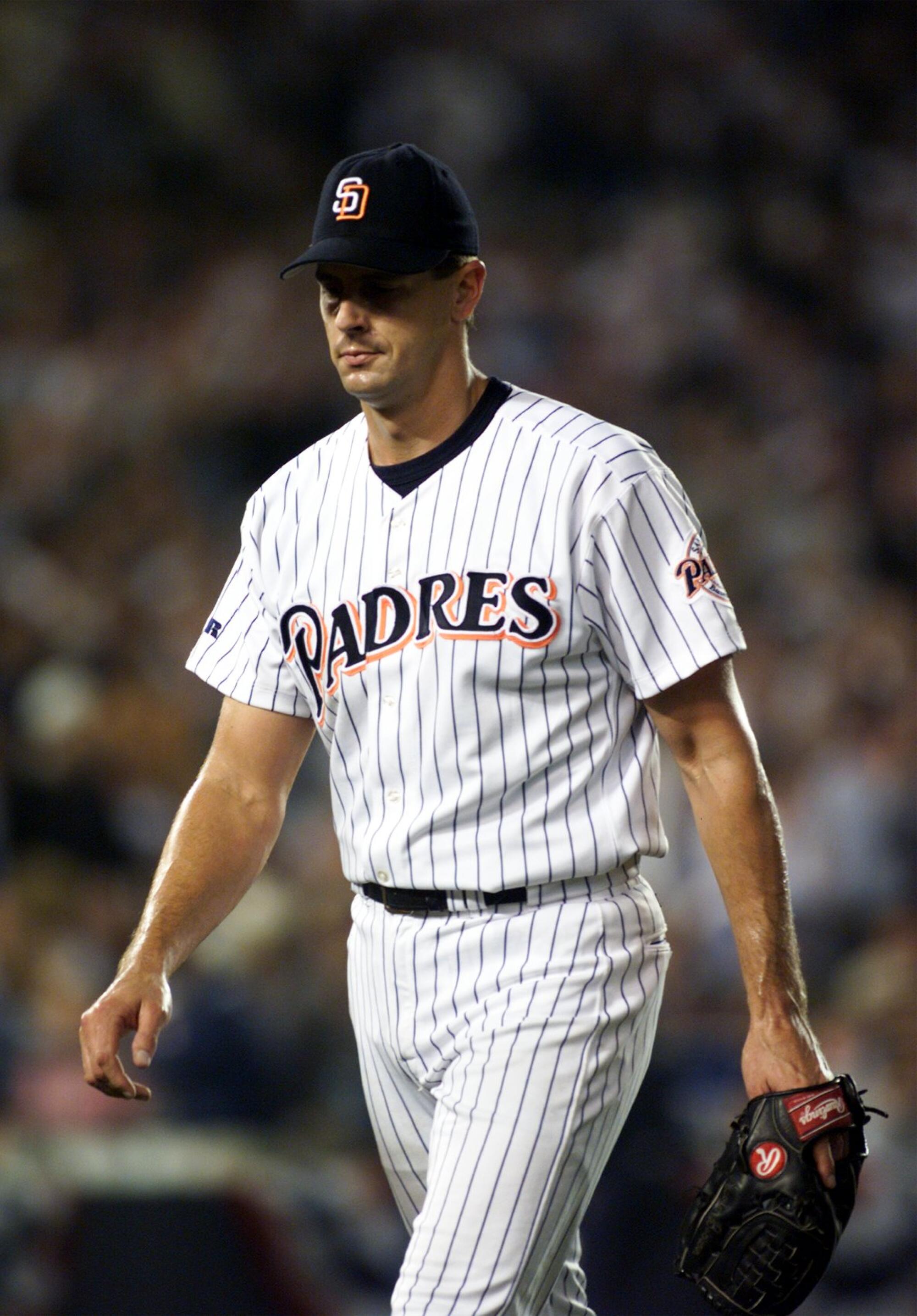

Sixteen years after the Padres signed Garvey, the Dodgers made former San Diego pitcher Kevin Brown baseball’s first $100-million player. The four-time All-Star, whose contract was worth $105 million, was fresh off an 18-win season and back-to-back trips to the World Series with the Florida Marlins and Padres.

Five months after the signing, when Brown made his first return to San Diego, the Padres played all sorts of money-themed songs through the public-address system, fans taunted him with chants of “traitor,” and a plane flew overhead dragging a banner that read, “Kevin: Buy us all a beer and we’ll forgive you.” Brown did the next-best thing: He absorbed a 3-0 loss.

“The Padres fans see the Dodgers and there’s a great deal of dislike, disdain, hatred, whatever you want to call it,” said Barry Axelrod, a longtime sports attorney and agent based in Encinitas. “I don’t know that the people in L.A. view the Padres with as much vitriol.”

On the contrary, Dodgers fans flock to San Diego when their team plays at Petco Park. Dodger Stadium is rich with history, but Petco, built in 2004, is loaded with conveniences and creature comforts.

“The Seidlers have recreated the Dodgers experience of the ‘80s,” said Pasadena’s Chris Rising, a lifelong Dodgers fan. “You go down there and the attendants say hello and they’re nice, they help you. It’s easy to get food. It’s a positive family experience, really a wonderful place to see a game.”

San Diego is in a unique position. It is the only city in Major League Baseball that doesn’t share its territory with another team from the NFL, NBA or NHL. When the Chargers moved to L.A. in 2017, the Padres were the last team standing. As professional sports go, the Padres are the only remaining cudgel with which to clobber L.A.

Even though there was no concerted effort to lure the Chargers north, and instead the Spanos family made the decision on their own to leave, that move sprayed lighter fluid on a smoldering resentment San Diego had for L.A. The anger was more visceral than when the Clippers left San Diego for L.A. in 1984.

This year’s baseball postseason could be the first to feature all three Southern California teams: the Dodgers, Angels and San Diego Padres.

“Had the Chargers moved anywhere else, had they moved to London, had they moved to Vegas, anywhere, it honestly would not have been near the deal it was by moving to L.A.,” said sportscaster Steve Hartman, who for years has done radio for XTRA 1360 in San Diego and TV for KTLA.

“And then the Chargers screwed up bigtime with their ‘Fight for L.A.,’ where the L.A people were offended. They were like, `‘Why did you take the Chargers out of San Diego? We don’t want them in L.A. We liked the fact that there was an NFL team in San Diego.’ So they totally messed that up, and they’re still paying the price for that gaffe.”

It’s not always easy living in the shadow of the nation’s second-largest media market, and when it comes to how they view L.A., some San Diegans seem to have a simultaneous inferiority and superiority complex.

“It’s a conundrum,” former Chargers center Nick Hardwick said. “We’re not L.A., but we’re not L.A. The good parts of L.A., we’re not that. But the bad parts of L.A., we’re also not that.”

Walton has a foot in both worlds. A star at both UCLA and in the NBA, he has an appreciation for L.A., but chooses to live in San Diego, on the edge of Balboa Park, a mile from the hospital where he was born.

“We’re very proud here,” Walton said. “Best beaches, best air, best bicycling, best water, fantastic airport, everything you can possibly imagine.”

To people in Los Angeles, San Diego is paradise. To lots of San Diegans, L.A. is “Smell-A.”

“All you have to do to understand that dynamic is go look at the 5 Freeway on Friday afternoon and on Sunday afternoon,” Walton said. “On Friday afternoon, all of Los Angeles comes to San Diego. On Sunday afternoon, they all go back.”

Walton, close friends with the Seidler family, is a Padres fan to the core.

“I’ve got my Padre uniform and my Padre hat and my Padre bat,” he said. “ ... I just wish I could play for them.”

Over the course of his illustrious 14-year NBA career, Walton collected nearly 5,000 rebounds. That required positioning and anticipation, some of which he learned as a young fan of the Padres when they played in the Pacific Coast League.

“At Westgate Park, I knew who was coming up, so that’s where I would position myself for the foul ball or home run,” he said, referring to the ballpark in what is now Mission Valley and specifically the northeast corner of the Fashion Valley Mall.

“When certain guys would come up, I’d say, `‘This guy is a left-handed pull hitter, so I’m going to get in the right-field bleachers along the first-base line.’ But when Tony Perez would come up, man, I’m going out into the outfield and I’m going to get that home run ball.

“I was quick to that ball. I was nine, 10 years old, and I was not reluctant to jump over the chairs to get to the ball that was bouncing around in the bleachers. And in the outfield, that was just a banked-up hill of grass.

“When you’re a tiny boy with red hair and a buzz cut, man, the ushers and ticket takers were always more than kind to little Billy.”

Cameron Crowe can relate. The writer/director whose classic movies include “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” “Jerry Maguire,” “Say Anything,” and the autobiographical “Almost Famous,” was raised in San Diego, is passionate about his hometown, and has a firm grasp on how it differs from L.A.

“Los Angeles is a different world,” Crowe said. “It’s showtime, it’s showbiz, it’s people live there to make a mark, or make a killing, and they move on, I feel. There are Angelenos for sure, but my experience is, if you sit in a coffee shop and listen to people talking, a lot of them are talking about trying to get a show made, or a script, or a TV show. The shadow of the entertainment business that runs L.A. creates sometimes a kind of a yearning desire for celebrity.

“You’re not going to hear that kind of stuff sitting in a coffee shop in San Diego. Mercifully. And I like L.A. But San Diego is in my bloodstream. Getting back to San Diego when you’ve been elsewhere is always so satisfying.”

While conceding the Padres have yet to fulfill the loftiest of expectations, Crowe said: “What they have done is created a lot of warm, personal memories that just keep cooking. And it amounts to a lot. And ultimately, there’s going to be a moment where all of it comes into play, and it’s coming. It’s coming.”

In August 2019, the “Almost Famous” musical made its debut at the Old Globe Theatre in Balboa Park. Crowe grew up in an apartment across the street.

“I was really nervous,” he said. “It’s a play about your family that’s going to play for the first time in your old hometown. It’s definitely the place you don’t want to come and do a belly flop.

“I had all this stress. I was driving down from L.A., and I got off the freeway in downtown, heading toward this apartment that they had gotten us, and I just felt all those San Diego feelings that were just so close to the surface my whole life. I just felt this warm wind come through the whole experience for me, and I just felt, this is where I should be. I belong here.”

He got to the apartment building, rode up the elevator, looked out the window and realized it overlooked Petco Park. The Padres were playing the Dodgers.

“I got to watch the game from the window,” he said. “I just felt like everything is right.”

Times staff writer Jorge Castillo contributed to this story.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.