‘Standing on the shoulders of giants.’ 1968: a year in sports like no other

- Share via

Forty-three deaths.

The Detroit Tigers were playing for something more than a pennant as they embarked on the 1968 baseball season.

Hundreds of homes destroyed. Thousands of stores looted and burned.

That spring, the Tigers forged a championship run and became a rallying point for a populace still reeling from violent riots the previous summer.

“When this city needed treatment for its ills in the worst way,” a Detroit Free Press editorial stated, “they have been the elixir that made us well again.”

It was a sign of the times.

Nineteen sixty-eight stands as a year that blurred the line between sports and the real world, with athletes swept up by Vietnam War protests, political tumult and racial tensions.

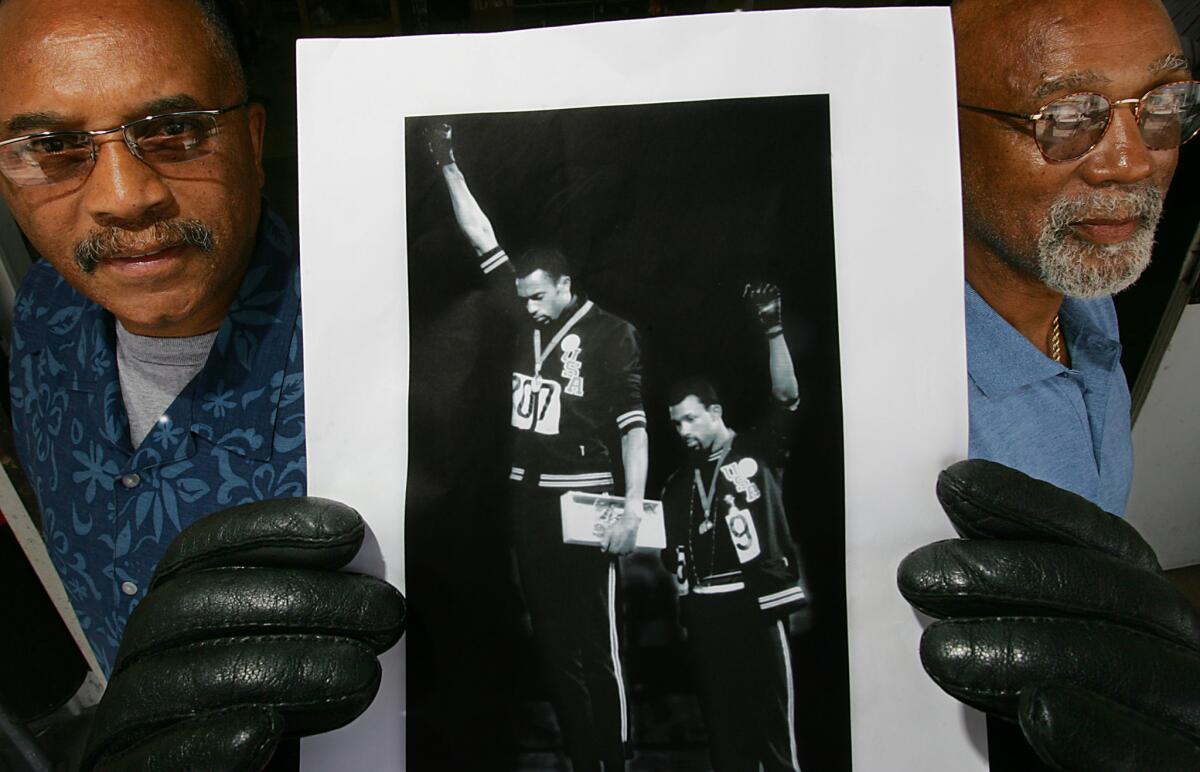

In Mexico City, American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos provided the defining image as they stood atop a podium at the Summer Olympics and raised black-gloved fists into the air.

Though troops had gunned down pro-democracy demonstrators students in the Mexican capital two weeks earlier just days before, Smith and Carlos were protesting something different — the treatment of blacks at home in the U.S.

“If I win, I am an American, not a black American,” Smith said. then. “But if I did something bad, then they would say 'a Negro.' We are black and we are proud of being black.”

Not that all the benchmarks from 1968 were political or social.

USC’s O.J. Simpson proved best in college football, as UCLA’s Lew Alcindor did in college basketball. The Boston Celtics, per usual, defeated the Lakers in the NBA finals.

1968: How a year of tumultuous events continues to shape our world »

In hockey, the NHL made a westward trek with expansion teams in Los Angeles and Oakland, blazing a trail for the likes of the Anaheim Ducks, San Jose Sharks and Vegas Golden Knights.

College basketball’s “Game of the Century” between UCLA and Houston offered a first glimpse at the future March Madness, with its massive television audience and a court plopped down in a football stadium.

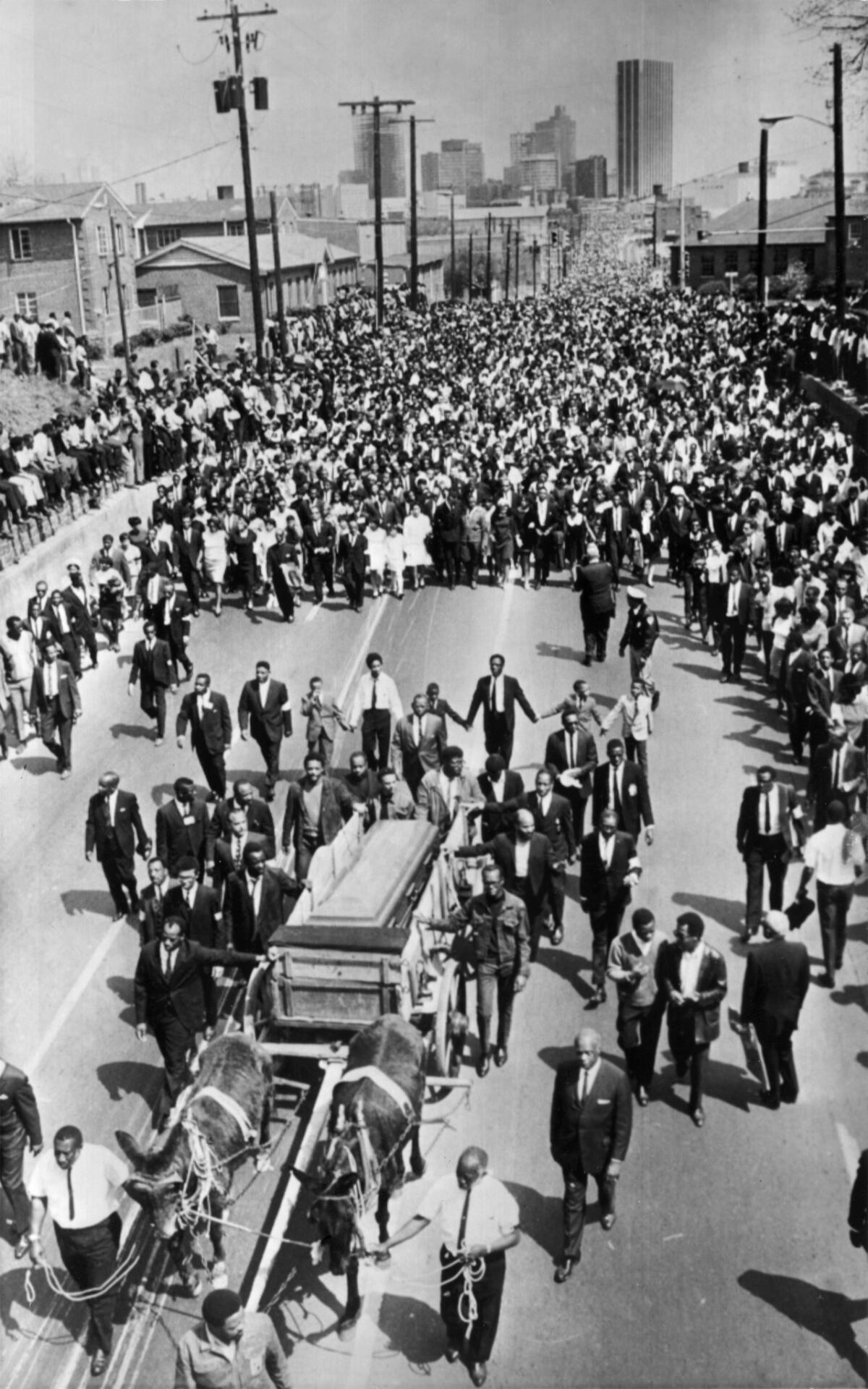

But issues of race and culture stole the spotlight as the NBA and Major League Baseball grappled with postponing games after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

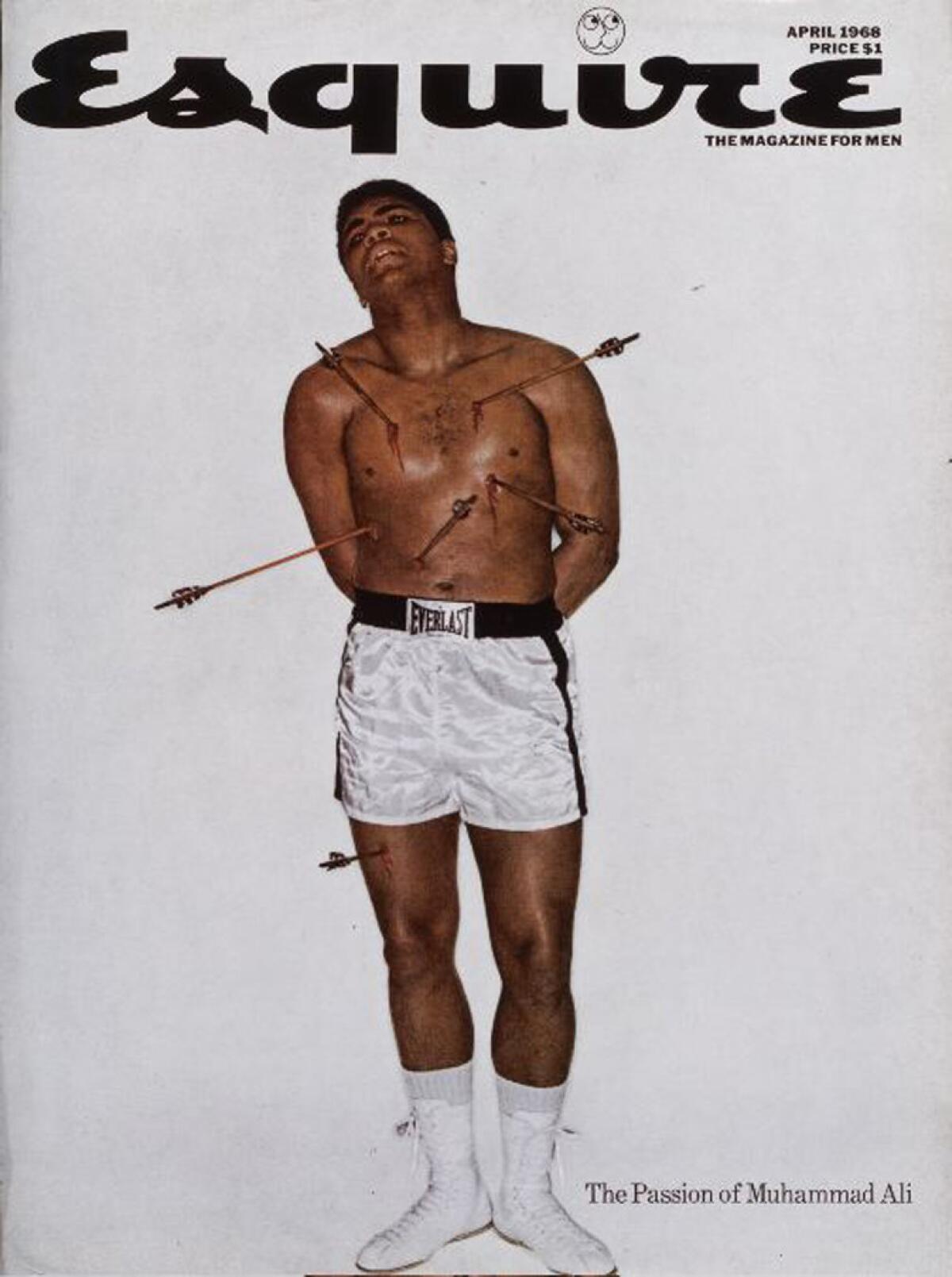

The debate grew louder as Arthur Ashe became the first black man to win a U.S. Open in tennis and the exiled Muhammad Ali continued to speak out against the war while appealing his conviction for draft evasion.

Sports served as a platform, a chance to be seen and heard by thousands in the stands and millions watching at home. The athletes might not have known it, but they were setting a precedent for today’s generation of activist players.

Colin Kaepernick, the former NFL quarterback who started the new trend of kneeling during the national anthem, has praised Smith and Carlos on social media: “I have read about them, studied their public protest, admired their courage and, like many others, I have emulated them.”

Half a century later, sports is still feeling reverberations from that year.

It makes sense that 1968 stands out in sports, if only because it ranks among the most remarkable — and turbulent — points in U.S. history.

The Tet Offensive marked a crossroads in the Vietnam War. King and Robert F. Kennedy were killed within months of each other. Police clashed with protesters outside the Democratic National Convention and the subsequent election of Richard Nixon soon divided the nation.

As the civil rights movement shifted to a new phase, sports dealt with persistent racial issues.

Though American athletes already had broken the color barrier in professional baseball, football and basketball, reaction to King’s death served as a reminder that the struggle for integration was far from over.

“I can remember that time because it was a time when a lot of us didn’t feel very patriotic,” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who changed his name from Alcindor after leaving UCLA, recalled at a recent Washington D.C. event.

League commissioners, team owners and players grappled with how to mourn the late civil rights leader — or even whether to mourn him. Though some were insistent upon showing respect, others had safety concerns as riots erupted in cities across the nation.

The NBA chose to proceed with its playoffs — Boston versus Philadelphia, Los Angeles against San Francisco — immediately after the shooting. Only when reigning stars Bill Russell of the Celtics and Wilt Chamberlain of the 76ers complained did the league agree to shut down for the next five days.

The baseball season was set to begin just before King’s funeral. With no clear directive from Commissioner William Eckert, teams had to decide for themselves.

Following the lead of Maury Wills and Roberto Clemente, all 25 members of the Pittsburgh Pirates came together to announce they would not play. Other teams quickly fell into line, re-scheduling their openers.

Only the Dodgers resisted, insistent upon holding their first game on a Tuesday night, hours after King’s services. Their opponent, the Philadelphia Phillies, threatened to forfeit.

“It angers me that the team which pioneered the advent of the Negro in baseball would take such a stand,” Phillies first baseman Bill White said.

The Dodgers eventually relented, postponing the game for a day.

A distinct momentum was building throughout sports. As author David Steele recalled recently: “Everything was building up to 1968, waiting to bubble over.”

“After Dr. King’s assassination, followed two months later by the assassination of Robert Kennedy, there was no holding back,” said Steele, who co-wrote “Silent Gesture” with Tommie Smith. “That was the case for Tommie and John in Mexico City and so many others of that generation. It was hard for anyone to argue that there was a separation between the real world and the sports world in America.”

Fans might not remember that Smith and Carlos ran the 200 meters in Summer Olympics. Or that Smith won gold, with Carlos finishing just behind an Australian to earn bronze.

But the photograph of their medals ceremony remains unforgettable.

The sprinters stood shoeless in solidarity with the poor, each bowing their head during the national anthem and raising a gloved fist in what was widely characterized as a “black power salute.”

In “Silent Gesture,” Smith wrote that it was actually a “human rights salute.”

The protest had its roots in a small organization, the Olympic Project for Human Rights, formed nearly a year earlier by San Jose State professor and social activist Harry Edwards.

OPHR sought the reinstatement of Ali’s heavyweight title, the hiring of more black coaches and the ouster of International Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage, who many people viewed as racist and anti-Semitic.

“As I looked at it from a sociological and ideological perspective,” Edwards recalled, “sport provided a tremendous opportunity to deal with some issues.”

There was talk of an Olympic boycott by black American athletes — ultimately, only Abdul-Jabbar and a few other basketball players declined to participate. As the IOC agreed to ban South Africa and Rhodesia over those countries’ discriminatory policies, the group shifted to another strategy.

When Smith and Carlos raised their fists on Oct. 16, boos rained down from the crowd at Estadio Olimpico Universitario. U.S. team officials subsequently expelled them from the athletes village.

The pair returned home to death threats and backlash in the media. Time magazine re-purposed the Olympic motto —Faster, Higher, Stronger — in writing that “‘Angrier, nastier, uglier’ better describes the scene in Mexico City …’’

But not everyone disapproved.

With the NFL season in full swing, St. Louis Cardinals player David Meggyesy refused to adhere to league policy on behavior during the anthem — stand in line, helmet under the left arm, right hand over the heart and face the flag.

Meggyesy, who is white, held his helmet in front of him and bowed his head while the anthem was played before a home game.

The linebacker said he drew inspiration from Smith and Carlos in deciding to protest the Vietnam War and — as he later stated in his book “Out of Their League” — “rampant racism” in pro football.

“In the NFL, a lot of white guys come from conservative or born-again backgrounds,” he wrote. “No matter how big the star, the blacks know the story of injustice.”

That included athletes who played for and against the Dallas Cowboys.

It did not matter that courts had ruled against Jim Crow laws mandating segregation in hotels, restaurants, parks and pools throughout much of the South. When opposing teams arrived in Dallas, their black players had to stay in separate hotels.

Even though President Lyndon Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act after King’s death, the law was not enforced in Dallas or surrounding areas. Former Cowboys fullback Don Perkins told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that housing available to him and his black teammates was “roach-infested.”

Several hours to the south, the University of Texas had yet to put a black player on the football field. The following season, the Longhorns would be the last all-white team to win a college national championship.

Racism wasn’t the only issue facing American athletes.

In the spring of 1967, Ali had cited his conversion to Islam as grounds for refusing to be inducted into the U.S. Army.

The heavyweight champion was stripped of his titles and sentenced to five years in prison. Though free on bail pending appeal, he was forbidden from traveling outside the U.S.

“I am not allowed to work in America and I’m not allowed to leave America,” he said during a paid appearance at a boat show in his hometown of Louisville in February 1968.

None of these punishments succeeded in quieting him. Through the year, Ali went on a college speaking tour and saw his popularity rebound with the burgeoning anti-war movement.

Speaking openly was not as easy for Ashe, who won the U.S. Open as an amateur that summer. The former UCLA star felt uneasy about serving as a role model for young black athletes.

“I am black, an American black,” he wrote. “But I am a ‘have’ and especially a capitalist. Personally, I represent me. Secondly, I represent us.”

Years later, he devoted himself to social causes, particularly relating to Haitian refugees and South Africa. He also shared his personal story while dying from AIDS caused by a blood transfusion.

Ashe’s burden “was the idea that all blacks have to give back in a certain way approved by the community,” Damion Thomas, a sports curator for the Smithsonian National Institute, said during a 2007 lecture entitled, “Don’t Tell Me How to Talk.”

Abdul-Jabbar also faced this challenge in 1968.

His interest in social issues dated back several years, when a white policeman fatally shot a black teenager in the Harlem neighborhood where he grew up. Rioting broke out amid conflicting accounts about whether the teen had brandished a knife.

Several years later, during his college career at UCLA, Abdul-Jabbar met with Harry Edwards and decided to skip Mexico City.

“The more confident and successful I became on the court, the more confident I felt about expressing my political convictions,” he wrote in his “Coach Wooden and Me” autobiography. “That personal progression reached its most controversial climax in 1968, when I refused to join the Olympic basketball team. That started a firestorm of criticism, racist epithets and death threats that people still ask me about today.”

It was also in 1968 that he became a Muslim and took a new name. But another three years would pass before he felt comfortable in announcing this to the world.

As he wrote: “… I seemed to reside in an exclusive neighborhood ‘Between A Rock and a Hard Place.’ ”

As 1968 drew to a close, the Detroit Tigers were in a hole.

After winning the American League pennant, they fell behind the St. Louis Cardinals three games to one in the World Series.

But in Game 5, left fielder Willie Horton made a throw that caught Cardinals star Lou Brock trying to score from second. The Tigers prevailed and wound up winning the title.

Horton’s role as catalyst was fitting, given that he had played high school ball in Detroit.

That fall, the city was still mending from race riots that left 43 dead. During the conflagration, as thousands of buildings were destroyed and police made more than 7,200 arrests, Horton had taken to the streets to plead for calm.

The Tigers felt the weight of their community, Horton later telling the New York Times that he and the other players sensed “if we could pull together as a team — that meant everybody, blacks and whites — perhaps we could set an example for the rest of the city.”

Around the same time, quarterback Joe Namath was leading the New York Jets to an American Football League title while similarly unifying his team.

Fellow players credited him with galvanizing a roster that could have been torn apart by racism.

Namath assumed this role even though he had attended Alabama, which was still several years away from suiting up its first black player. When his college teammates discovered a photo of his Pennsylvania high school team, which was integrated, they gave him the n-word as a nickname.

“It was really out of sight, man,” Namath said in a Playboy interview. “When I got to the University of Alabama, coming from where I came from, I couldn’t believe it.”

A half-century later, it is possible to look back on the upheaval of those times — the effect it had on sports — and see a clear precedent. When Kaepernick took a knee rather than standing for the national anthem before San Francisco 49ers games, many of the same questions were rekindled.

Should athletes who protest be derided as unpatriotic or even anti-American? Should they be praised for using their celebrity to oppose injustice?

Addressing the audience in Washington D.C. in April, Abdul-Jabbar harkened back to the Olympic gesture by Smith and Carlos, calling it “a watershed moment in civil rights history.”

Now a professor emeritus at UC Berkeley, Edwards paid similar tribute as he counseled Kaepernick and other athletes confronting present-day issues. He pointed to 1968.

“Go back and read the history,” he told them. “You guys are standing on the shoulders of giants.”

david.wharton@latimes.com | Twitter: @LATimesWharton

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.