It was safety first for UCLA, Seahawks great Kenny Easley, who is about to enter the Pro Football Hall of Fame

- Share via

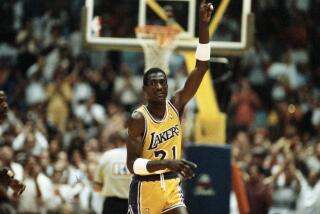

Kenny Easley played with an impeccable sense of anticipation. That’s what helped him make 32 interceptions as an NFL safety, and paved his path to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, where Saturday his bronze bust will be unveiled.

But what about the anticipation of UCLA? His alma mater deserves some credit for allowing him to patrol the back end of the defense, rather than directing him to the other side of the ball, as so many schools hoped to do.

“The majority of the schools that came in were recruiting me as a quarterback,” said Easley, 58. “I didn’t want to play quarterback. I would have just been a good athlete playing quarterback, but I was a really good free safety because I good ball-hawking skills, just like a 10-year-old I didn’t mind throwing my body into the mix.”

So when Easley narrowed his choices down to Michigan and UCLA, legendary Wolverines coach Bo Schembechler talked to him about playing quarterback.

“He couldn’t understand why a guy who was offered the chance to play quarterback at the University of Michigan in front of 100,000 people, why would you want to play free safety,” Easley said. “He even told me, ‘Anybody can do that.’ ”

Easley didn’t hear the same pitch from UCLA’s Terry Donahue. He wanted Easley as a free safety.

“That sort of sealed the deal right there,” Easley said. “My dad even asked the question of Terry Donahue: ‘If my son decides to go to UCLA, you’re not going to get him there and switch him to quarterback?’ And Terry Donahue said, ‘Absolutely not. If your son wants to play free safety, we’re going to play him there.’ ”

Recalled Donahue: “The reason he felt like that was at that particular time there were not a lot of African-American quarterbacks playing in the NFL. He didn’t feel his chances to get to the NFL — and that was his No. 1 priority — would be as good at the quarterback position.

“He and his father had me promise that I would never play him at quarterback, and it was a hard promise to keep. Because he was such a dominant player and could have played any position that touches the ball or plays in the defensive backfield.”

Easley was such a remarkable athlete, Donahue said, that he was outstanding on the basketball court, and “you’d have thought you were watching a young Arthur Ashe” in those infrequent times he picked up a tennis racket.

As it happened, safety was an ideal fit. After his college career, Easley went on to become the No. 4 choice in the 1981 draft by Seattle, was AFC Rookie of the Year, and the league’s Defensive Player of the Year in 1984. A devastating hitter, he made five Pro Bowls and was All-Pro in four consecutive seasons, from 1982-85.

“In my pursuit at trying to be the best, I always felt like I was shooting up to his level because he was the standard,” said safety Ronnie Lott, who entered the NFL the same season as Easley yet made it to the Hall of Fame 17 years sooner. “Kenny’s skills transcended the game.”

Easley is the sixth UCLA player to be enshrined in the Canton, Ohio, institution, joining Troy Aikman, Tom Fears, Jimmy Johnson, Jonathan Ogden, and Bob Waterfield.

The NFL career of Easley lasted just seven seasons, as he walked away from the game in 1987 in large part because of a kidney ailment brought on, he believes, by large doses of painkillers. He was traded to the then-Phoenix Cardinals but failed his physical. He believes the Seahawks knew of his kidney condition but didn’t inform him.

That led to an impasse between Easley and the Seahawks that lasted more than a decade. Easley said there were two reasons the ice eventually thawed. First, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen bought the team and pushed for reconciliation with one of its greatest players.

“And second,” Easley said, “my children were coming of age, they had never seen me play football, and they didn’t know much about my career. I didn’t have any pictures around the house of my athletic career. So when I got the call from [Seahawks executive] Gary Wright indicating that Paul Allen had said to him that they shouldn’t put another player in the ring of honor before putting Kenny Easley in there …

“I hadn’t spoken to anybody in the organization for 15 years. So Gary called me and told me what Paul had said. So thinking about my children … It was the proper time to do it. I’m glad my children got an opportunity to be a part of it, learn about their father and what he had done, and how successfully he had done it.”

Easley, added to that ring of honor in 2002, is the fourth Seahawks player to make it to Canton, joining Steve Largent, Walter Jones, and the late Cortez Kennedy.

Easley had multiple interceptions in each of his seven seasons, leading the league in that category in 1984. He also was used on occasion as a punt returner, doing so most frequently in ’84, when the Seahawks reached the AFC championship game.

To this day, just as he did when picking a college, Easley finds himself defending the position. He’s just the 10th safety in the Hall of Fame, and at least three of those played cornerback, too.

“When people look at defenses, they look at defensive linemen, outside linebackers, middle linebackers and the corners,” he said.

Saturday, the football world will be looking at a safety. Despite what that Michigan coaching icon said, it isn’t a job for just anybody.

Follow Sam Farmer on Twitter @LATimesfarmer

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.