- Share via

Even Mother Nature has turned her back on Lake Los Angeles.

The lakes that gave the community its name dried up years ago, taking with them the high-end restaurant, a planned country club and designs to turn the sprawling town on the eastern edge of the Antelope Valley into a resort. Left behind are boarded-up homes and businesses, with residents caught in a squeeze between rising rents and declining purchasing power.

“The town just kind of went,” said Erika Schwerdt, program manager for a social services agency housed on the site of an abandoned middle school. “This area is really high in the index for crime, for lack of jobs. There’s so many people living in RVs in the middle of nowhere because they literally have nowhere to go.”

In many ways, hope evaporated when the water did.

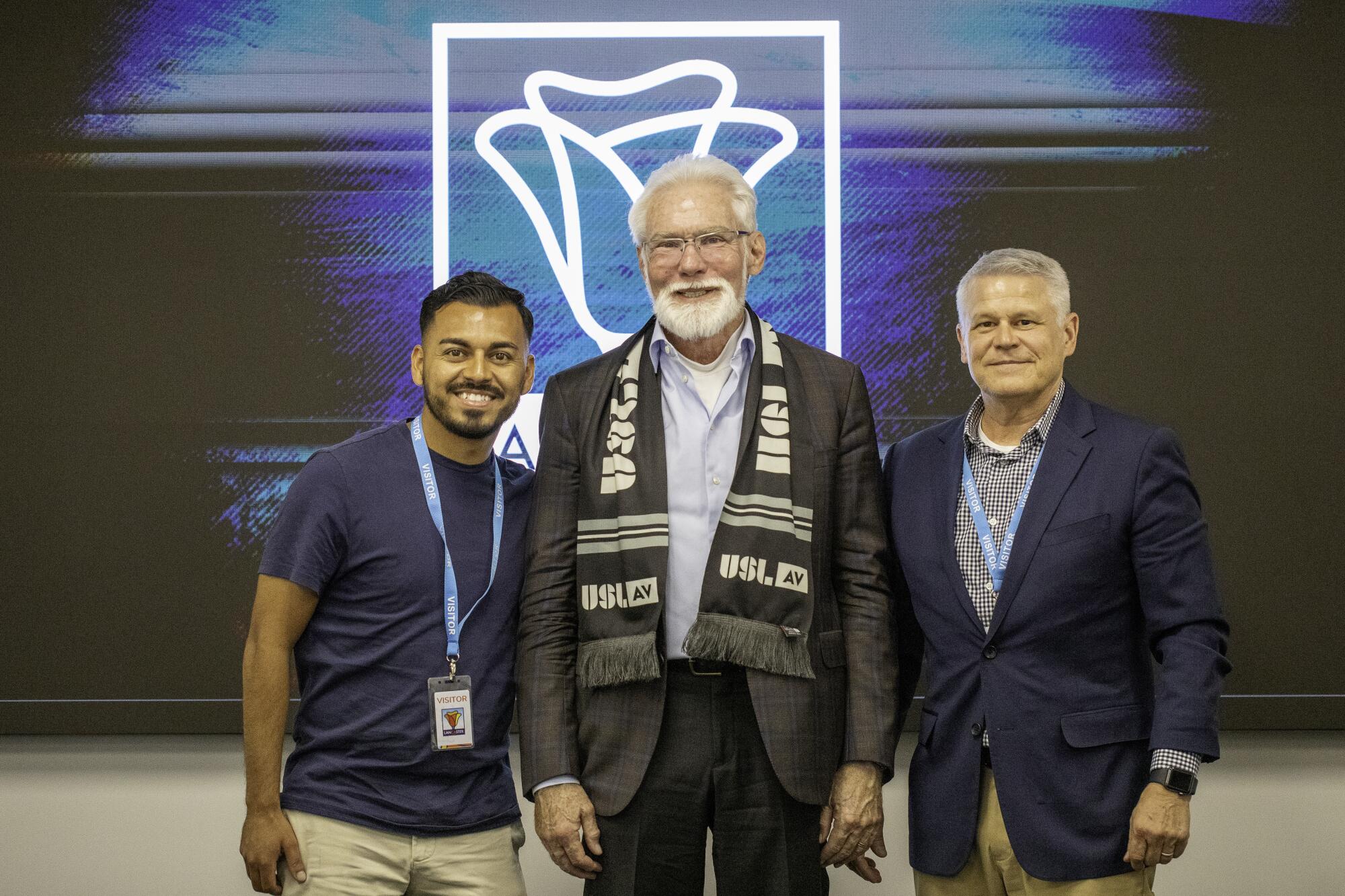

John Smelzer can’t replenish the lakes, but his plans to place a professional soccer team in the Antelope Valley can bring back the hope, Schwerdt said.

“This,” she said, “is a game-changer.”

On Wednesday, Smelzer will formally announce he is bringing a USL League One franchise to the Antelope Valley in 2025, the biggest step yet in a project that has been in the works for years. While he didn’t necessarily set out to change lives when he first had the idea, he’s quickly finding out that’s exactly what he’s doing.

“There is not just an opportunity for economic revitalization, but also the rekindling of community spirit and pride,” said Kiel McClung, a former U.S. youth international soccer player from the Antelope Valley.

Christian Hernandez, an engineer for Northrop Grumman and the soccer coach at Palmdale High, agreed. “It’s a perfect times. There’s so many soccer fans that this community has, that I think it really is going to have an impact.”

Added Lancaster Mayor R. Rex Parris: “If the community adopts the team, anything we can do to increase that identification, the better it’s going to be for the city and for the people who live here. Ultimately, it’s are we creating an environment for people to thrive in? That requires that sense of community.”

For Smelzer, 58, a longtime sports and media executive who began his career on the 1994 World Cup organizing committee before going on to work with the NFL, as well as Fox and NBC sports, it was a case of supply and demand for a community that was growing and changing demographically.

“I just love the game. I believe in the game for all the right reasons,” he said. “It unifies people, it brings people together. And I just saw a community that needed it. What else am I going to do? Be a consultant and advisor?”

The Antelope Valley lost its only professional sports team in 2020 when the Lancaster JetHawks folded after nearly a quarter-century, vacating a 4,500-seat ballpark the city had spent $14.5 million to build and millions more to maintain. The JetHawks’ attendance fell by half over that time, and when the city placed an independent league team in the ballpark last summer, the crowds it drew were even smaller.

That left the city with an empty stadium in a majority Hispanic community of nearly 500,000 that no longer cared much for baseball. What it did have was a 35-field soccer complex, one of the largest in the country, and some of the best youth soccer players in Southern California.

“The interest in soccer in this community is substantial,” Parris said. “You’d be hard-pressed, I think, to find a kid who didn’t play it.”

That convinced Smelzer, a longtime LAFC season-ticket holder, if he could supply professional soccer to the Antelope Valley, there would be a demand for it. How much of a demand? When he sent his first email to the City of Lancaster asking for a meeting to discuss putting a team in the baseball stadium, the nearly instantaneous reply was “how about Tuesday?”

“I’ve got nothing against baseball. But this is a soccer market,” Smelzer said as he walked along the first-base stands at the ballpark formerly known as The Hanger.

“We’re just tapping into a passion that they already have.”

Alan Rothenberg, the former U.S. Soccer president whose instincts made a phenomenal success of a 1994 U.S. World Cup many observers were sure would be a monumental failure, believes Smelzer has tapped into something special.

“He has the know-how and the passion,” Rothenberg said of his longtime friend. “He’s done a great job of getting the city behind him and arranging for a proper facility. What he needs is the financial support and he’s working diligently to secure that. When he does, I think he’ll have a winner.”

The USL League One, a 12-team professional league, is on the third tier of the U.S. soccer pyramid, two spots below MLS and one below the USL Championship. For an expansion fee of approximately $5 million — about 1/100th of an MLS expansion fee and about a quarter of what it costs to join the USL Championship — Smelzer and his investors got exclusive rights to put an as-of-yet unnamed team in the Antelope Valley. The City of Lancaster, meanwhile, agreed to meet Smelzer’s $1 million with $10 million of its own to renovate the ballpark and turn it into a 5,300-seat soccer-specific stadium, one of just four between San Diego and Sacramento.

In return, Smelzer has given city hall a seat on the team’s board.

That was just the first part of the equation. Although the Antelope Valley is in Los Angeles County, it doesn’t always feel part of it. Residents frequently refer to the area south of the Newhall Pass as “down below,” as if it’s a different land with a different reality. Smelzer, who lives in West L.A., was from the “down below” so he asked Francisco “Panchito” Ramírez, a Lake Los Angeles native and former UC Riverside soccer player, to show him around.

It proved to be a brilliant move.

“He’s a great kid with an amazing story,” said McClung who, along with William Ortiz, a former Marine and freelance sports photographer, introduced Ramírez to Smelzer.

Ramírez, 27, not only lived and played in the area, he earned a masters in leadership and policy at the University of Michigan after graduating from Riverside with a double major. He then returned to the Valley to found The Dreamers Soccer Clinic, a volunteer-based nonprofit for underprivileged youth.

“He just he said to me, ‘we’re going to meet every coach in this valley. We’re going to meet community members, we’re going to meet school board members, we’re going to meet teachers,’” Smelzer said. “It was hundreds of hours just meeting people, talking to people, just listening. I kept saying to Panchito, ‘What do we have to actually do?’ And he said, ‘Just be there. Just listen.’

“Just to listen to people and say, ‘This is your club, this is your community. We care what you think. We want you to come to our games.’”

One of the first stops was the trailer where Schwerdt works for Strength Based Community Change, separated from The Hanger by more than 25 miles of dusty, straight-as-an-arrow desert roads. That was the first sign Smelzer was serious.

“Nobody comes out,” Schwerdt told Smelzer. “The fact that you all drove out here is amazing. And it means a lot.”

He and Ramírez have been back several times.

To underscore just how much that means, Schwerdt tells the story of a 15-year-old boy, a talented soccer player who couldn’t find the right program to keep him busy. He eventually drifted into the wrong crowd and was found dead just down the street from the SBCC trailer.

“The goal is to get the kids motivated,” Schwerdt said. “We see soccer as multifaceted way for people to develop not just professional skills, but [to] get them through to college and to get them through life.”

That was a need Smelzer heard over and over during his meetings with Ramírez. Although the Antelope Valley had a vibrant youth soccer scene, the best players had to go down below, to the San Fernando Valley or further, to hone their skills. For many working-class families, the time and money required was a deal-breaker.

So Smelzer’s team will include an elite academy program where the most talented local kids can play for free.

“Their parents can’t take them to L.A. for a kids’ soccer practice. This club is going to change that,” said Ramírez, whose own parents once skipped their rent payment to get their son to a college showcase.

“It’s going to allow opportunities for those kids, kids like me, kids with aspiration,” he continued. “This club’s going to be in their backyard. We no longer need to travel down below.”

Yet that’s just the first step. Ramírez and McClung are among just a handful of players from the Antelope Valley who have gone on to play for major colleges, and fewer still have succeeded as professionals. To address that, Smelzer said he wants a significant part of his roster to be players such as Ramírez and McClung, players who come from the area and can provide both inspiration and familiarity.

The Lancaster JetHawks had a chance to avoid the fate of dozens of other minor league teams eliminated by MLB on Wednesday. But that lifeline didn’t come through.

“What’s that expression, ‘If you see it, you can be it?’” Smelzer said. “Fans in the stands, they won’t just recognize the players, they’ll know them. They’ll have played with them, they’ll recognize them as part of the community.”

Smelzer’s desire to build the team from the bottom up is already succeeding, even though the first game is more than 18 months away. Two weeks ago he, Ramírez and Ortiz pulled together a list of 65 potentially key supporters and invited them to a party to celebrate the team’s launch. As of Friday, more than 650 people had RSVP’d for the event.

Schwerdt is one of those who was invited, but she’ll be sending someone else to the party. Her community, after all, has had a long, painful history of big plans that dried up.

“People are looking for something familiar,” she said of her clients, 95% of whom are Hispanic. “Certainly the community wants this. But will they engage the community?”

Smelzer promises she won’t be disappointed.

“Most people are not betting on this community, right? So if we come along and we do it and we’re sincere about it, we’re genuine, when we say we are your club, they’re going to reciprocate,” he said.

“If we’re really walking the walk. we have to be here. And I’m just crazy enough that I’m willing to do it.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.