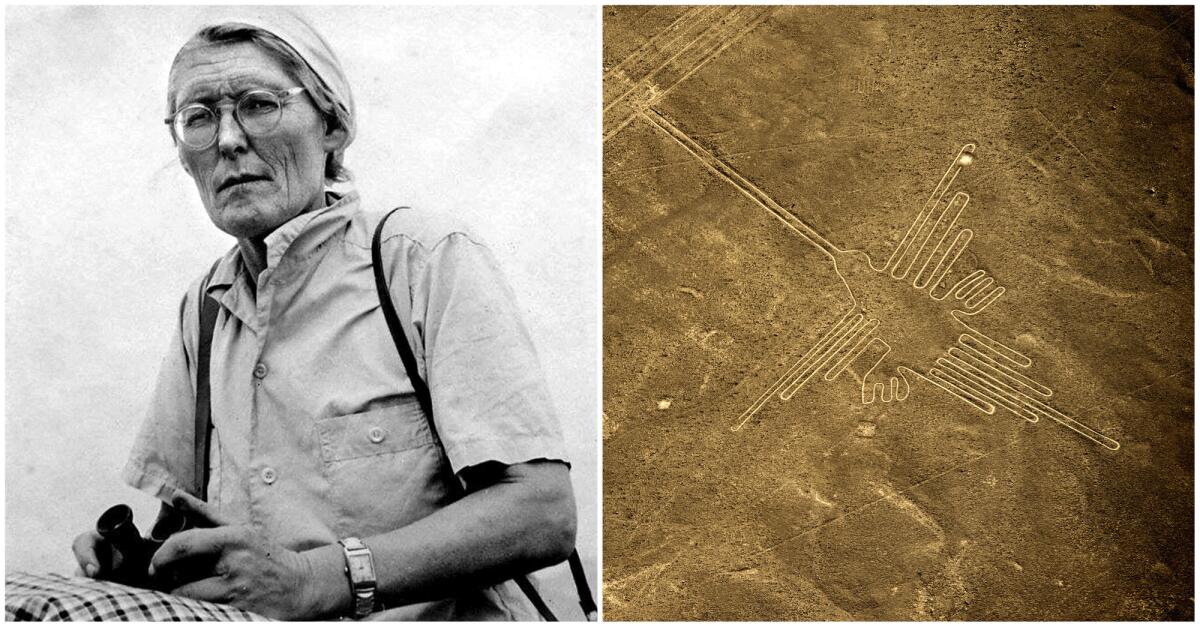

Remembering archaeologist Maria Reiche, who devoted her life to investigating Peru’s Nazca Lines

German mathematician and archaeologist Maria Reiche (1903-98) researched the Nazca Lines, beginning in 1940, and helped secure recognition for them. They are now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Right, aerial view of the hummingbird figure.

- Share via

NAZCA, Peru — Maria Reiche was devoted to the Nazca Lines, so much so that she was known as the “Lady of the Lines.” The mathematician and archaeologist spent her last 25 years living in the Hotel Nazca Lines in this small city.

The well-appointed hotel (where we also stayed) offers a nightly 45-minute planetarium show about the lines and about Reiche, who was born in Germany in 1903 and came to Peru to teach at a German school in Cuzco.

Paul Kosok, an American historian who was doing field work in the area, had seen the sun set at the winter solstice (June 21 in the Southern Hemisphere) right over one of the lines. He needed an assistant with a mathematical background and hired Reiche.

The hotel is full of people who knew her. Planetarium lecturer Edgar Azabache was a friend. Another worker has a key to the room she lived in, and with a whisper to the front desk, you can catch a glimpse of her quarters and hear stories too.

Whether Reiche’s theories hold up or not — she believed the lines were a vast celestial calendar that likely served to mark times for sowing, harvesting and distributing food — Nazca residents think it was she who put the lines on the map, so to speak.

She built a hut in the desert (you can still visit it by taking a taxi or bus or joining a local tour) and lived there without running water or electricity for 40 years. She spent her days climbing ladders, mapping the lines, cleaning them and doing endless mathematical calculations to try to figure out their significance.

Locals thought she was either crazy or a witch, Azabache said, when they saw her in the desert moving stones, and they would leave her food.

Reiche assisted the Peruvian government in making the geoglyphs’ location into a national park in the 1950s. And when the Peruvians were going to dig irrigation canals in the 1950s across the middle of the Nazca pampas, she fought the local and national bureaucracies to protect the linesIn 1994, the Nazca Lines were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Reiche died in 1998 at age 95. She was blind and had skin cancer from 60 years under the desert sun. It was said that she lectured to hotel visitors weekly until the very end.

On the wall outside her room, a plaque reads: “If I had a hundred lifetimes, I would have given them to Nazca. And if I had to make a thousand sacrifices, I would have made them, if for Nazca.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.